Working Out While Losing Weight Keeps Muscles 'Young', Study Finds

A mystery from our evolutionary past.

A mystery from our evolutionary past.

A mystery from our evolutionary past.

A mystery from our evolutionary past.

Here's what we know.

Here's what we know.

A recent study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology suggests that the rising popularity of extreme political candidates may be driven by how voters link their personal identities to their political opinions. The research provides evidence that when people feel an issue defines who they are as individuals, they tend to adopt more radical positions and favor politicians who do the same.

The researchers conducted this series of investigations to explore the psychological reasons why voters might prefer extreme candidates over moderate ones from their own party. Previous explanations have focused on structural factors like the way primary elections are organized or changes in the pool of people running for office.

But the authors behind the new research sought to better understand whether a voter’s internal connection to an issue is a significant factor. They focused on a concept called identity relevance, which is the degree to which an attitude signals to others and to oneself the kind of person someone is or aspires to be.

“Elected officials in the United States are increasingly extreme. The ideological extremity of members of Congress from both parties has steadily grown since the 1970s, reaching a 50-year high in 2022,” said study author Mohamed Hussein of Columbia University.

“State legislatures show similar trends. A recent analysis of more than 84,000 candidates running for state office revealed that extreme candidates are winning at higher rates than at any time in the last 30 years. We were interested in understanding why extreme candidates are increasingly elected.”

“So far, research in this area has focused on structural factors (e.g., the structure of primary elections),” Hussein explained. “In our work, we wanted to pivot the conversation to more psychological factors. Specifically, we tested if the identity relevance of people’s attitudes causes them to be drawn to extreme candidates. ”

The researchers conducted a series of studies to test their hypothesis. In the first study, 399 participants who identified as Democrats read about a fictional candidate named Sam Becker who was running for a seat in the House of Representatives. Some participants read that Becker held moderate views on climate change, while others read that he held extreme views. The researchers measured how much the participants felt their own attitudes on climate change were relevant to their identity.

The results suggests that as identity relevance increased, the participants reported having more extreme personal views on the issue. Those with high identity relevance showed a preference for the extreme version of Sam Becker and a dislike for the moderate version. This study provides initial evidence that the more someone sees an issue as a reflection of their character, the more they favor radical politicians.

The second study involved 349 participants and used a more complex choice task to see if these patterns held across different topics. Participants were shown pairs of candidates with varying ages, genders, and professional backgrounds. One candidate in each pair held a moderate position on a social issue, while the other held an extreme position.

The researchers tested five separate issues: abortion, gun control, immigration, climate change, and transgender rights. The data suggests that across all these topics, higher identity relevance predicted a greater likelihood of choosing the extreme candidate. Additionally, participants with high identity relevance reported being more receptive to hearing the views of the extreme candidate.

In the third study, the researchers aimed to see if they could change a person’s identity relevance by shifting their perception of what their political party valued. They recruited 584 Democrats and asked them to read a news article about the priorities of the Democratic National Committee. One group read that the party was prioritizing corn subsidies, a topic that is generally not a core identity issue for most voters.

The results suggests that when participants believed their party viewed corn subsidies as a priority, they began to see the issue as more relevant to their own identity. This shift in identity relevance led them to adopt more extreme personal views on the topic. Consequently, these participants showed a higher preference for candidates who supported radical changes to agricultural subsidies.

This experiment also allowed the researchers to rule out other factors that might influence candidate choice. They measured whether participants felt more certain, more moral, or more knowledgeable about the issue. The analysis provides evidence that identity relevance influences candidate choice primarily through its effect on attitude extremity rather than through these other psychological states.

The fourth study sought to prove that this effect can occur even when people have no factual information about a topic. The researchers presented 752 participants with a fictitious ballot initiative called Prop DW. The participants were told nothing about what the proposal would actually do.

Some participants were told their political party had taken a position on Prop DW, while others were told the party had no stance. Even without knowing the details of the policy, those who believed their party had a stance reported that Prop DW felt more identity-relevant. These individuals developed more extreme attitudes and favored candidates who took extreme positions on the made-up issue.

This finding suggests that the psychological pull toward extremity is not necessarily based on a deep understanding of policy. Instead, it seems to be a reaction to the social and personal significance assigned to the topic. It also suggests that people can form strong, radical opinions on matters they do not fully understand if they feel those matters define their social group.

Studies five and six moved away from group dynamics to see if individual reflection could trigger the same results. The researchers used a digital tool that allowed 514 participants to have a live conversation with a large language model. In one condition, the computer program was instructed to help participants reflect on how their views on corn subsidies related to their core values and sense of self.

This reflection process led to a measurable increase in identity relevance. Participants who reflected on their identity reported a higher desire for clarity, which means they wanted their opinions to be certain and distinct. This desire for clarity pushed them toward more extreme views and a higher probability of choosing an extreme candidate.

The final study involving 807 participants replicated this effect with a more rigorous comparison group. In this version, the control group also discussed corn subsidies with the language model but was not prompted to think about their personal identity. The results provides evidence that only the participants who specifically linked the issue to their identity showed a significant shift toward extremity.

The researchers note that this effect was symmetric across political parties. Both Democrats and Republicans showed the same pattern of moving toward extreme candidates when an issue felt relevant to their identity. This suggests that the psychological mechanism is a general feature of human behavior rather than a trait specific to one side of the political aisle.

“Across six studies with over 3,000 participants, we found that the more people see their political attitudes as tied to identity, the more likely they are to choose extreme, versus moderate, candidates,” Hussein told PsyPost. “The more central fighting climate change felt to the identity of participants, the more they liked the extreme Sam and the more they disliked the moderate Sam. Put simply, identity relevance increased liking of extreme candidates but decreased liking of moderate ones.”

“These results were remarkably robust. Across studies we tested a range of issues including climate change, abortion, immigration, transgender rights, gun control, and corn subsidies . We even created a fictitious issue (“Prop DW”) that participants had no information about. Across issues, we found that when we framed the issue as central to their identity, people formed more extreme views on it and then preferred extreme candidates who promised bolder action. Even on a made-up issue, identity relevance pushed people toward extremes.”

“These results were also robust regardless of how we talked about candidate extremity,” Hussein continued. “In addition to having candidates describe themselves as extreme, we also signaled extremity in different ways. In some studies, the candidates endorsed different policies, some that were moderate and others that were extreme.”

“In other studies, we held the policy constant but changed the level of action that candidates supported (e.g., increasing a subsidy by a small amount compared to a large amount). Lastly, in some studies, we explicitly labeled candidates as ‘moderate’ or ‘extreme’ on an issue. Regardless of how candidate extremity was described to participants, the results held.”

But there are some potential misinterpretations and limitations to consider regarding this research. One limitation is that the studies were conducted within the specific political context of the United States. The American two-party system might encourage a greater need for distinct, polarized identities compared to countries with multiple competing parties.

Future research could explore whether these findings apply to people in other nations with different electoral structures. It would also be useful to investigate whether certain personality types are more prone to linking their identity to political issues. Some individuals may naturally seek more self-definition through their opinions than others.

Another direction for future study involves finding ways to decrease political tension. If identity relevance is a primary driver of the preference for extreme candidates, it suggests that finding ways to de-emphasize the personal significance of political stances might lead to more moderate dialogue. Interventions that help people feel secure in their identity without needing to hold radical opinions could potentially reduce social polarization.

“Politics has always been personal, but it’s becoming more identity-defining than ever,” Hussein said. “And when politics becomes identity-relevant, our research suggests that extremity gains in appeal. Illuminating this psychological process helps us understand today’s political landscape and provides a roadmap for how to change it. Our results suggest that if we can loosen the grip of identity on politics, the appeal of extreme candidates might start to wane.”

The study, “Why do people choose extreme candidates? The role of identity relevance,” was authored by Mohamed A. Hussein, Zakary L. Tormala, and S. Christian Wheeler.

Experienced musicians tend to possess an advantage in short-term memory for musical patterns and a small advantage for visual information, according to a large-scale international study. The research provides evidence that the memory benefit for verbal information is much smaller than previously thought, suggesting that some earlier findings may have overrepresented this link. These results, which stem from a massive collaborative effort involving 33 laboratories, were published in the journal Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science.

The study was led by Massimo Grassi and a broad team of researchers who sought to address inconsistencies in past scientific literature. For many years, scientists have used musicians as a model for understanding how intense, long-term practice changes the brain and behavior. While many smaller studies suggested that musical training boosts various types of memory, these individual projects often lacked the statistical power to provide a reliable estimate of the effect.

The researchers aimed to establish a community-driven standard for future studies by recruiting a much larger group of participants than typical experiments in this field. They also wanted to explore whether other factors, such as general intelligence or personality traits, might explain why musicians often perform better on cognitive tests. By using a shared protocol across dozens of locations, the team intended to provide a more definitive answer regarding the scope of the musical memory advantage.

To achieve this goal, the research team recruited 1,200 participants across 15 different countries. This group consisted of 600 experienced musicians and 600 nonmusicians who were matched based on their age, gender, and level of general education. The musicians in the study were required to have at least 10 years of formal training and be currently active in their practice.

The nonmusicians had no more than two years of training and had been musically inactive for at least five years. This strict selection process ensured that the two groups represented clear ends of the musical expertise spectrum. Each participant completed the same set of tasks in a laboratory setting to maintain consistency across the 33 different research units.

The primary measures included three distinct short-term memory tasks involving musical, verbal, and visuospatial stimuli. In the musical task, participants listened to a melody and then judged whether a second melody was identical or different. The verbal task required participants to view a sequence of digits on a screen and recall them in the correct order.

For the visuospatial task, participants watched dots appear in a grid and then had to click on those positions in the sequence they were shown. Additionally, the researchers measured fluid intelligence using the Raven Advanced Progressive Matrices and crystallized intelligence through a vocabulary test. They also assessed executive functions with a letter-matching task and collected data on personality and socioeconomic status.

The researchers found that musicians performed significantly better than nonmusicians on the music-related memory task. This difference was large, which suggests that musical expertise provides a substantial benefit when dealing with information within a person’s specific domain of skill. This finding aligns with the idea that long-term training makes individuals much more efficient at processing familiar types of data.

In contrast, the advantage for verbal memory was very small. This suggests that the benefits of music training do not easily transfer to the memorization of words or numbers. The researchers noted that some previous studies showing a larger verbal benefit may have used auditory tasks, where musicians could use their superior hearing skills to gain an edge.

For visuospatial memory, the study found a small but statistically significant advantage for the musicians. This provides evidence that musical training might have a slight positive association with memory for locations and patterns. While this effect was not as large as the music-specific memory gain, it suggests a broader cognitive difference between the two groups.

The statistical models used by the researchers revealed that general intelligence and executive functions were consistent predictors of memory performance across all tasks. When these factors were taken into account, the group difference for verbal memory largely disappeared. This suggests that the minor verbal advantage seen in musicians may simply reflect their slightly higher average scores on general intelligence tests.

Musicians also tended to score higher on the personality trait of open-mindedness. This trait describes a person’s curiosity and willingness to engage with new experiences or complex ideas. The study suggests that personality and family background are important variables that often distinguish those who pursue long-term musical training from those who do not.

Data from the study also indicated that musicians often come from families with a higher socioeconomic status. This factor provides evidence that access to resources and a stimulating environment may play a role in both musical achievement and cognitive development. These background variables complicate the question of whether music training directly causes better memory or if high-performing individuals are simply more likely to become musicians.

As with all research, there are some limitations. Because the study was correlational, it cannot confirm that musical training is the direct cause of the memory advantages. It remains possible that children with naturally better memory or higher intelligence are more likely to enjoy music lessons and stick with them for over a decade.

Additionally, the study focused on young adults within Western musical cultures. The results might not apply to children, elderly individuals, or musicians trained in different cultural traditions. Future research could expand on these findings by tracking individuals over many years to see how memory changes as they begin and continue their training.

The team also noted that the study only measured short-term memory. Other systems, such as long-term memory or the ability to manipulate information in the mind, were not the primary focus of this specific experiment. Future collaborative projects could use similar large-scale methods to investigate these other areas of cognition.

The multilab approach utilized here helps correct for the publication bias that often favors small studies with unusually large effects. By pooling data from many locations, the researchers provided a more realistic and nuanced view of how expertise relates to general mental abilities. This work sets a new benchmark for transparency and reliability in the field of music psychology.

Ultimately, the study suggests that while musicians do have better memory, the advantage is most prominent when they are dealing with music itself. The idea that learning an instrument provides a major boost to all types of memory appears to be an oversimplification. Instead, the relationship between music and the mind is a complex interaction of training, personality, and general cognitive traits.

The study, “Do Musicians Have Better Short-Term Memory Than Nonmusicians? A Multilab Study,” was authored by Massimo Grassi, Francesca Talamini, Gianmarco Altoè, Elvira Brattico, Anne Caclin, Barbara Carretti, Véronique Drai-Zerbib, Laura Ferreri, Filippo Gambarota, Jessica Grahn, Lucrezia Guiotto Nai Fovino, Marco Roccato, Antoni Rodriguez-Fornells, Swathi Swaminathan, Barbara Tillmann, Peter Vuust, Jonathan Wilbiks, Marcel Zentner, Karla Aguilar, Christ B. Aryanto, Frederico C. Assis Leite, Aíssa M. Baldé, Deniz Başkent, Laura Bishop, Graziela Kalsi, Fleur L. Bouwer, Axelle Calcus, Giulio Carraturo, Victor Cepero-Escribano, Antonia Čerič, Antonio Criscuolo, Léo Dairain, Simone Dalla Bella, Oscar Daniel, Anne Danielsen, Anne-Isabelle de Parcevaux, Delphine Dellacherie, Tor Endestad, Juliana L. d. B. Fialho, Caitlin Fitzpatrick, Anna Fiveash, Juliette Fortier, Noah R. Fram, Eleonora Fullone, Stefanie Gloggengießer, Lucia Gonzalez Sanchez, Reyna L. Gordon, Mathilde Groussard, Assal Habibi, Heidi M. U. Hansen, Eleanor E. Harding, Kirsty Hawkins, Steffen A. Herff, Veikka P. Holma, Kelly Jakubowski, Maria G. Jol, Aarushi Kalsi, Veronica Kandro, Rosaliina Kelo, Sonja A. Kotz, Gangothri S. Ladegam, Bruno Laeng, André Lee, Miriam Lense, César F. Lima, Simon P. Limmer, Chengran K. Liu, Paulina d. C. Martín Sánchez, Langley McEntyre, Jessica P. Michael, Daniel Mirman, Daniel Müllensiefen, Niloufar Najafi, Jaakko Nokkala, Ndassi Nzonlang, Maria Gabriela M. Oliveira, Katie Overy, Andrew J. Oxenham, Edoardo Passarotto, Marie-Elisabeth Plasse, Herve Platel, Alice Poissonnier, Neha Rajappa, Michaela Ritchie, Italo Ramon Rodrigues Menezes, Rafael Román-Caballero, Paula Roncaglia, Farrah Y. Sa’adullah, Suvi Saarikallio, Daniela Sammler, Séverine Samson, E. G. Schellenberg, Nora R. Serres, L. R. Slevc, Ragnya-Norasoa Souffiane, Florian J. Strauch, Hannah Strauss, Nicholas Tantengco, Mari Tervaniemi, Rachel Thompson, Renee Timmers, Petri Toiviainen, Laurel J. Trainor, Clara Tuske, Jed Villanueva, Claudia C. von Bastian, Kelly L. Whiteford, Emily A. Wood, Florian Worschech, and Ana Zappa.

Blink, and you might lose it!

Blink, and you might lose it!

An analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2009–2020) found that men with higher sunlight affinity tend to have fewer depressive symptoms. They also reported sleeping problems less often; however, their sleep durations tended to be shorter. The paper was published in PLOS ONE.

In the context of this study, “sunlight affinity” is a novel metric proposed by the authors to measure an individual’s tendency to seek and enjoy natural sunlight. It combines psychological factors (preference for sun) and behavioral factors (actual time spent outdoors). Generally, the drive for sunlight is influenced by biological factors such as circadian rhythms, melatonin suppression, and serotonin regulation.

People with high sunlight affinity tend to report improved mood, energy, and alertness during bright daytime conditions. This tendency is partly genetic but is also shaped by developmental experiences, climate, and cultural habits. Conversely, low sunlight affinity may be associated with discomfort in bright light or a preference for dim environments.

While sunlight affinity is conceptually related to light sensitivity and seasonal affective patterns, it is not a clinical diagnosis. In environmental psychology, it helps explain preferences for outdoor activities and sunlit living or working spaces. In health contexts, moderate sunlight affinity can promote behaviors that support vitamin D synthesis and circadian stability.

Lead author Haifeng Liu and his colleagues investigated the associations between sunlight affinity and symptoms of depression and sleep disorders in U.S. men. They examined two dimensions of sunlight affinity: sunlight preference (how often a person chooses to stay in the sun versus the shade) and sunlight exposure duration (how much time a person spends outdoors). They noted that while recent findings indicate light therapy might help reduce depressive symptoms and improve sleep, the impact of natural sunlight exposure remains underexplored.

The authors analyzed data from 7,306 men who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2009 and 2020. NHANES is a continuous, nationally representative U.S. program that combines interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests to assess the health, nutritional status, and disease prevalence of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population.

The researchers selected males aged 20–59 years who provided all the necessary data. These individuals completed assessments for sunlight affinity, depressive symptoms (using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9), sleep disorder symptoms (answering, “Have you ever told a doctor or other health professional that you have trouble sleeping?”), and sleep duration.

Sunlight affinity was assessed by asking participants, “When you go outside on a very sunny day for more than one hour, how often do you stay in the shade?” and by asking them to report the time they spent outdoors between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM over the previous 30 days.

The results showed that participants with a higher preference for sunlight and longer exposure durations tended to have fewer depressive symptoms. They also reported sleep problems less often, though their total sleep time tended to be shorter.

“This study revealed that sunlight affinity was inversely associated with depression and trouble sleeping and positively associated with short sleep in males. Further longitudinal studies are needed to confirm causality,” the authors concluded.

The study sheds light on the links between sunlight affinity, depression, and sleep problems. However, it should be noted that the cross-sectional study design does not allow for causal inferences. Additionally, all study data were based on self-reports, leaving room for reporting bias to have affected the results.

The paper, “Associations of sunlight affinity with depression and sleep disorders in American males: Evidence from NHANES 2009–2020,” was authored by Haifeng Liu, Jia Yang, Tiejun Liu, and Weimin Zhao.

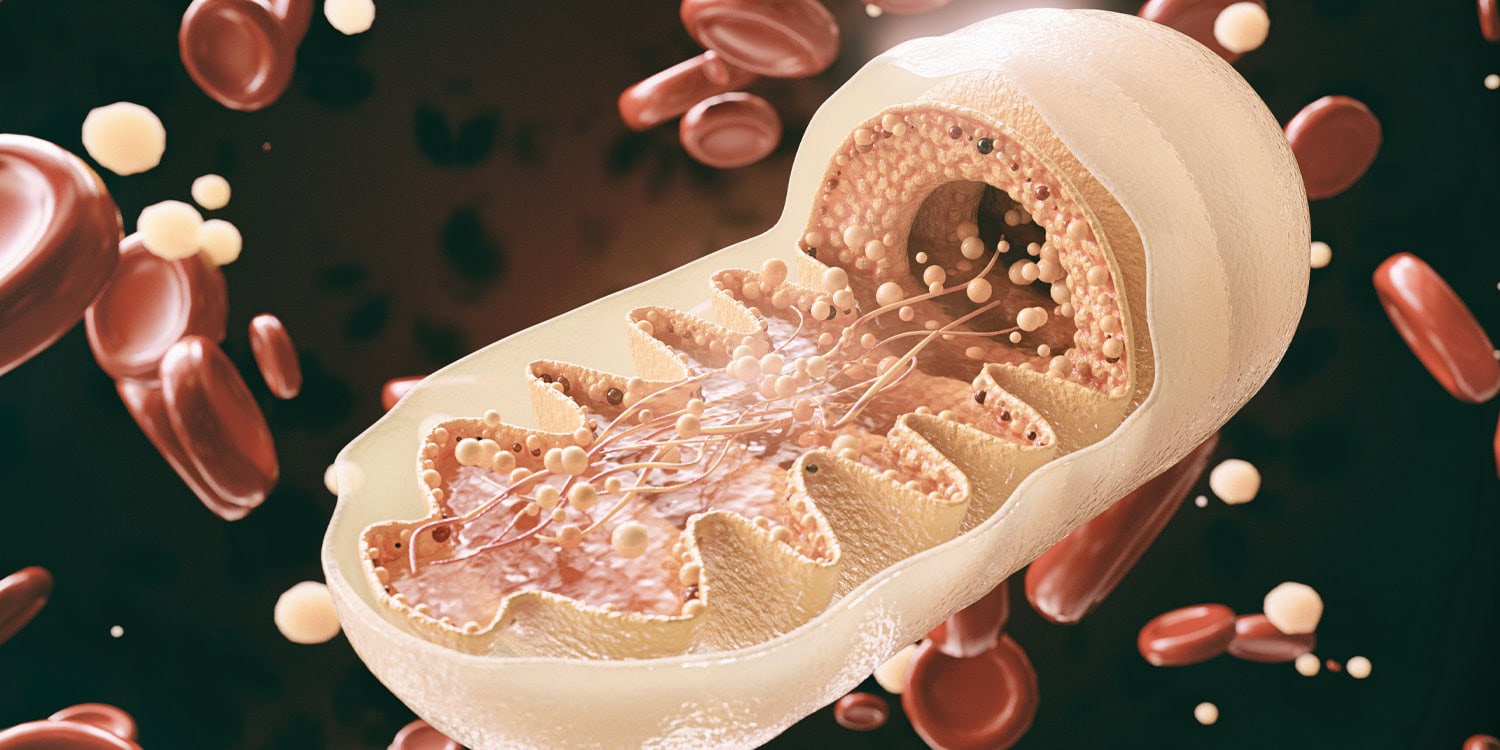

Researchers have discovered that Alzheimer’s disease may be reversible in animal models through a treatment that restores the brain’s metabolic balance. This study, published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, demonstrates that restoring levels of a specific energy molecule allows the brain to repair damage and recover cognitive function even in advanced stages of the illness. The results suggest that the cognitive decline associated with the condition is not an inevitable permanent state but rather a result of a loss of brain resilience.

For more than a century, people have considered Alzheimer’s disease an irreversible illness. Consequently, research has focused on preventing or slowing it, rather than recovery. Despite billions of dollars spent on decades of research, there has never been a clinical trial of any drug to reverse and recover from the condition. This new research challenges that long held dogma.

The study was led by Kalyani Chaubey, a researcher at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. She worked alongside senior author Andrew A. Pieper, who is a professor at Case Western Reserve and director of the Brain Health Medicines Center at Harrington Discovery Institute. The team included scientists from University Hospitals and the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center.

The researchers focused on a molecule called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, known as NAD+. This molecule is essential for cellular energy and repair across the entire body. Scientists have observed that NAD+ levels decline naturally as people age, but this loss is much more pronounced in those with neurodegenerative conditions. Without proper levels of this metabolic currency, cells become unable to execute the processes required for proper functioning and survival.

Previous research has established a foundation for this approach. A 2018 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that supplementing with NAD+ precursors could normalize neuroinflammation and DNA damage in mice. That earlier work suggested that a depletion of this molecule sits upstream of many other symptoms like tau protein buildup and synaptic dysfunction.

In 2021, another study published in the same journal found that restoring this energy balance could reduce cell senescence, which is a state where cells stop dividing but do not die. This process is linked to the chronic inflammation seen in aging brains.

Additionally, an international team led by researchers at the University of Oslo recently identified a mechanism where NAD+ helps correct errors in how brain cells process genetic information. That study, published in Science Advances, identified a specific protein called EVA1C as a central player in helping the brain manage damaged proteins.

Despite these promising leads, many existing supplements can push NAD+ to supraphysiologic levels. High levels that exceed what is natural for the body have been linked to an increased risk of cancer in some animal models. The Case Western Reserve team wanted to find a way to restore balance without overshooting the natural range.

They utilized a compound called P7C3-A20, which was originally developed in the Pieper laboratory. This compound is a neuroprotective agent that helps cells maintain their proper balance of NAD+ under conditions of overwhelming stress. It does not elevate the molecule to levels that are unnaturally high.

To test the potential for reversal, the researchers used two distinct mouse models. The first, known as 5xFAD, is designed to develop heavy amyloid plaque buildup and human like tau changes. The second model, PS19, carries a human mutation in the tau protein that causes toxic tangles and the death of neurons. These models allow scientists to study the major biological hallmarks of the human disease.

The researchers first confirmed that brain energy balance deteriorates as the disease progresses. In mice that were two months old and pre-symptomatic, NAD+ levels were normal. By six months, when the mice showed clear signs of cognitive trouble, their levels had dropped by 30 percent. By twelve months, when the disease was very advanced, the deficit reached 45 percent.

The core of the study involved a group of mice designated as the advanced disease stage cohort. These animals did not begin treatment until they were six months old. At this point, they already possessed established brain pathology and measurable cognitive decline. They received daily injections of the treatment until they reached one year of age.

The results showed a comprehensive recovery of function. In memory tests like the Morris water maze, where mice must remember the location of a submerged platform, the treated animals performed as well as healthy controls. Their spatial learning and memory were restored to normal levels despite their genetic mutations.

The mice also showed improvements in physical coordination. On a rotating rod test, which measures motor learning, the advanced stage mice regained their ability to balance and stay on the device. Their performance was not statistically different from healthy mice by the end of the treatment period.

The biological changes inside the brain were equally notable. The treatment repaired the blood brain barrier, which is the protective seal around the brain’s blood vessels. In Alzheimer’s disease, this barrier often develops leaks that allow harmful substances into the brain tissue. Electronic microscope images showed that the treatment had sealed these gaps and restored the health of supporting cells called pericytes.

The researchers also tracked a specific marker called p-tau217. This is a form of the tau protein that is now used as a standard clinical biomarker in human patients. The team found that levels of this marker in the blood were reduced by the treatment. This finding provides an objective way to confirm that the disease was being reversed.

Speaking about the discovery, Pieper noted the importance of the results for future medicine. “We were very excited and encouraged by our results,” he said. “Restoring the brain’s energy balance achieved pathological and functional recovery in both lines of mice with advanced Alzheimer’s. Seeing this effect in two very different animal models, each driven by different genetic causes, strengthens the new idea that recovery from advanced disease might be possible in people with AD when the brain’s NAD+ balance is restored.”

The team also performed a proteomic analysis, which is a massive screen of all the proteins in the brain. They identified 46 specific proteins that are altered in the same way in both human patients and the sick mice. These proteins are involved in tasks like waste management, protein folding, and mitochondrial function. The treatment successfully returned these protein levels to their healthy state.

To ensure the mouse findings were relevant to humans, the scientists studied a unique group of people. These individuals are known as nondemented with Alzheimer’s neuropathology. Their brains are full of amyloid plaques, yet they remained cognitively healthy throughout their lives. The researchers found that these resilient individuals naturally possessed higher levels of the enzymes that produce NAD+.

This human data suggests that the brain has an intrinsic ability to resist damage if its energy balance remains intact. The treatment appears to mimic this natural resilience. “The damaged brain can, under some conditions, repair itself and regain function,” Pieper explained. He emphasized that the takeaway from this work is a message of hope.

The study also included tests on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. These are the cells that make up the blood brain barrier in people. When these cells were exposed to oxidative stress in the laboratory, the treatment protected them from damage. It helped their mitochondria continue to produce energy and prevented the cells from dying.

While the results are promising, there are some limitations to the study. The researchers relied on genetic mouse models, which represent the rare inherited forms of the disease. Most people suffer from the sporadic form of the condition, which may have more varied causes. Additionally, human brain samples used for comparison represent a single moment in time, which makes it difficult to establish a clear cause and effect relationship.

Future research will focus on moving this approach into human clinical trials. The scientists want to determine if the efficacy seen in mice will translate to human patients. They also hope to identify which specific aspects of the brain’s energy balance are the most important for starting the recovery process.

The technology is currently being commercialized by a company called Glengary Brain Health. The goal is to develop a therapy that could one day be used to treat patients who already show signs of cognitive loss. As Chaubey noted, “Through our study, we demonstrated one drug-based way to accomplish this in animal models, and also identified candidate proteins in the human AD brain that may relate to the ability to reverse AD.”

The study, “Pharmacologic reversal of advanced Alzheimer’s disease in mice and identification of potential therapeutic nodes in human brain,” was authored by Kalyani Chaubey, Edwin Vázquez-Rosa, Sunil Jamuna Tripathi, Min-Kyoo Shin, Youngmin Yu, Matasha Dhar, Suwarna Chakraborty, Mai Yamakawa, Xinming Wang, Preethy S. Sridharan, Emiko Miller, Zea Bud, Sofia G. Corella, Sarah Barker, Salvatore G. Caradonna, Yeojung Koh, Kathryn Franke, Coral J. Cintrón-Pérez, Sophia Rose, Hua Fang, Adrian A. Cintrón-Pérez, Taylor Tomco, Xiongwei Zhu, Hisashi Fujioka, Tamar Gefen, Margaret E. Flanagan, Noelle S. Williams, Brigid M. Wilson, Lawrence Chen, Lijun Dou, Feixiong Cheng, Jessica E. Rexach, Jung-A Woo, David E. Kang, Bindu D. Paul, and Andrew A. Pieper.

Here's the verdict.

Here's the verdict.

The potential is immense.

The potential is immense.

The 'superionic phase' is real.

The 'superionic phase' is real.

Videos promoting #testosteronemaxxing are racking up millions of views. Like “looksmaxxing” or “fibremaxxing” this trend takes something related to body image (improving your looks) or health (eating a lot of fibre) and pushes it to extreme levels.

Testosterone or “T” maxxing encourages young men – mostly teenage boys – to increase their testosterone levels, either naturally (for example, through diet) or by taking synthetic hormones.

Podcasters popular among young men, such as Joe Rogan and Andrew Huberman, enthusiastically promote it as a way to fight ageing, enhance performance or build strength.

However, taking testosterone when there’s no medical need has serious health risks. And the trend plays into the insecurities of young men and developing boys who want to be considered masculine and strong. This can leave them vulnerable to exploitation – and seriously affect their health.

We all produce the sex hormone testosterone, but levels are naturally much higher in males. It’s produced mainly in the testes, and in much smaller amounts in the ovaries and adrenal glands.

Testosterone’s effects on the body are wide ranging, including helping you grow and repair muscle and bone, produce red blood cells and stabilise mood and libido.

During male puberty, testosterone production increases 30-fold and drives changes such as a deeper voice, developing facial hair and increasing muscle mass and sperm production.

It’s normal for testosterone levels to change across your lifetime, and even to fluctuate daily (usually at their highest in the morning).

Lifestyle factors such as diet, sleep and stress can also affect how much testosterone you produce.

Natural testosterone levels generally peak in early adulthood, around the mid-twenties. They then start to progressively decline with age.

A doctor can check hormone levels with a blood test. For males, healthy testosterone levels usually range between about 450 and 600 ng/dL (nanograms per decilitre of blood serum). Low testosterone is generally below 300 ng/dL.

In Australia, taking testosterone is only legal with a doctor’s prescription and ongoing supervision. The only way to diagnose low testosterone is via a blood test.

Testosterone may be prescribed to men diagnosed with hypogonadism, meaning the testes don’t produce enough testosterone.

This condition can lead to:

Hypogonadism has even been linked to early death in men.

Hypogonadism affects around one in 200 men, although estimates vary. It is more common among older men and those with diabetes or obesity.

Yet on social media, “low T” is being framed as an epidemic among young men. Influencers warn them to look for signs, such as not developing muscle mass or strength as quickly as hoped – or simply not looking “masculine”.

Extreme self-improvement and optimisation trends spread like wildfire online. They tap into common anxieties about masculinity, status and popularity.

Conflating “manliness” with testosterone levels and a muscular physical appearance exploits an insecurity ripe for marketing.

This has fuelled a market surge for “solutions” including private clinics offering “testosterone optimisation” packages, supplements claiming to increase testosterone levels and influencers on social media promoting extreme exercise and diet programs.

There is evidence some people are undergoing testosterone replacement therapy, even when they don’t have clinically low levels of testosterone.

Taking testosterone as a medication can suppress the body’s own production, by shutting down the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which controls testosterone and sperm production.

While testosterone production can recover after you stop taking testosterone, this can be slow and is not guaranteed, particularly after long-term or unsupervised use. This means some men may feel a significant difference when they stop taking testosterone.

Testosterone therapy can also lead to side effects for some people, including acne and skin conditions, balding, reduced fertility and a high red blood cell count. It can also interact with some medications.

So there are added risks from using testosterone without a prescription and appropriate supervision.

On the black market, testosterone is sold in gyms, or online via encrypted messaging apps. These products can be contaminated, counterfeit or incorrectly dosed.

People taking these drugs without medical supervision face potential infection, organ damage, or even death, since contaminated or counterfeit products have been linked to toxic metal poisoning, heart attacks, strokes and fatal organ failure.

T maxxing offers young men an enticing image: raise your testosterone, be more manly.

But for healthy young men without hypogonadism, the best ways to regulate hormones and development are healthy lifestyle choices. This includes sleeping and eating well and staying active.

To fight misinformation and empower men to make informed choices, we need to meet them where they are. This means recognising their drive for self-improvement without judgement while helping them understand the real risks of non-medical hormone use.

We also need to acknowledge that young men chasing T maxxing often mask deeper issues, such as body image anxiety, social pressure or mental health issues.

Young men often delay seeking help until they have a medical emergency.

If you’re worried about your testosterone levels, speak to your doctor.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The words you choose may reveal more than you realize.

The words you choose may reveal more than you realize.

People across three very different societies—Scotland, Pakistan, and Papua—show notable cultural and age-related differences in how much they prefer decorated objects, according to a new study published in Evolutionary Psychology.

Human ornamentation has existed for tens of thousands of years, appearing in archaeological sites spanning North Africa to Australia. Theories as to why ornamentation is so widespread have ranged from perceptual processing advantages, social identity, and costly signaling, to evolved aesthetic tendencies.

Many prior studies have focused on prehistoric records or Indigenous groups far removed from Western influence, leaving open the question of whether modern cultural shifts, particularly Western minimalism, have altered people’s underlying preferences for ornamentation.

To address this gap, Piotr Sorokowski and colleagues examined whether cultural environment and age shape people’s appreciation for decorated versus plain objects. Their approach was grounded in evolutionary psychology and developmental research showing that even across diverse societies, children often draw, adorn, and embellish objects spontaneously. This raises the possibility that preference for ornamentation might emerge early in life and only later be molded or suppressed by cultural norms.

The researchers recruited 215 parent-child dyads across three cultural contexts: Scotland (the most WEIRD location), Pakistan (moderately WEIRD), and Papua (a minimally Western-influenced region). Dyads were recruited online in Scotland and Pakistan through an international research company, and in person in Papua via snowball sampling.

The final sample included 84 dyads from Scotland, 88 from Pakistan, and 43 from Papua (Dani and Yali tribes in the Baliem Valley and Yalimo Highlands). Adults, who completed the task first, and children completed the same object-choice paradigm independently.

Each participant viewed six pairs of images representing everyday items: three plates and three shirts. In every pair, one item appeared in a plain design while the other incorporated a simple ornament such as a floral motif, leaf pattern, or abstract line drawing. The researchers selected objects expected to be universally recognizable and culturally neutral to facilitate comparable interpretation across societies.

Participants indicated which object they preferred for each pair, and the presentation order and left-right positioning of ornamented items were systematically varied to reduce patterns and side biases. Demographic data, including age, sex, and place of residence, were also collected. From the six choices, the researchers derived three preference scores for each participant: one for ornamented plates, one for ornamented shirts, and one aggregated score reflecting overall ornamentation preference.

Across all analyses, strong cultural differences emerged. Participants from Papua showed the highest preference for ornamented objects, followed by participants from Pakistan, while Scottish participants demonstrated the lowest enthusiasm for decoration. These differences were robust across plates, shirts, and overall scores. The results support the idea that cultural context, particularly Western minimalism, suppresses ornamentation preferences.

The researchers also observed age differences, but primarily within the Scottish sample. Children generally preferred ornamented objects more than adults. This pattern was strongest in Scotland, where it was significant for both shirts and the aggregated preference score. In Pakistan, the difference was more modest and found only for shirts; in Papua, adults and children showed similarly high enthusiasm for ornamented designs. Correlations also revealed moderate similarity between parents and children within dyads, and ornamentation preference tended to decline with age in the Scottish sample.

A key finding is that children across cultures, especially in the Western sample, favored ornamentation more than adults, suggesting that younger individuals may display a more “baseline” or biologically rooted preference before cultural norms exert their influence. The authors argue that Papuan adults may be closer than Western adults to this natural preference level, given their similarity to children’s choices.

One limitation is that only two object types (plates and shirts) were used; broader categories such as home décor, architecture, or sculpture were not tested.

Overall, the findings suggest that humans may possess an evolutionarily grounded inclination toward ornamentation, one that can be dampened, but not erased, by cultural forces such as Western minimalism.

The research, “Is Ornamentation a Universal Human Preference? Cross-Cultural and Developmental Evidence From Scotland, Pakistan, and Papua,” was authored by Piotr Sorokowski, Jerzy Luty, Wiktoria Jędryczka, and Michal Mikolaj Stefanczyk.

An analysis of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe data found that individuals born between 1945 and 1957 (baby boomers) who were in stable marriages experience greater well-being in old age compared to those who are single or in less stable relationships. Participants with lower education who have divorced showed even lower well-being. The study was published in the European Journal of Population.

Romantic couple relationships play a central role in adult life. A relationship with a romantic partner provides companionship, emotional security, and a sense of belonging. Through daily interactions, romantic partners influence each other’s emotions, behaviors, and life choices.

Supportive and stable relationships are associated with better mental health, including lower levels of depression, anxiety, and loneliness. They can also buffer the effects of stress by offering emotional reassurance and practical help during difficult periods.

High-quality romantic relationships are linked to better physical health, including lower risk of cardiovascular disease and improved immune functioning. Partners shape each other’s health behaviors, such as diet, physical activity, substance use, and adherence to medical advice. Conversely, conflictual or unsupportive relationships can increase stress, negatively affect mental health, and contribute to poorer physical outcomes.

Study author Miika Mäki and his colleagues note that well-being in old age reflects combined experiences over the entire life course. Previous studies indicate that marriage dissolutions have long-term negative implications on well-being and health that can persist even among those who remarry. Similarly, unstable partnerships and multiple relationship transitions or long-term singlehood are all associated with higher levels of depression and stress and lower social and emotional support.

To explore this in more detail, these authors conducted a study in which they examined the links between well-being in old age and romantic relationship history. They hypothesized that individuals with stable marital relationship histories will experience higher well-being after age 60 compared to those with less stable relationship histories.

To explore this, they analyzed data from the SHARELIFE interviews of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE covers households with at least one member over 50 years of age in all EU countries, Switzerland, and Israel. The SHARELIFE interviews were conducted in 2008 and 2017. Respondents were asked to report, among other things, on their childhood circumstances and their romantic relationships, including all cohabitational, marital, and dating relationships.

This analysis was based on the data of individuals born between 1945 and 1957, who were at least 60 years old in 2017 (all part of the baby boomer generation). Data from a total of 18,256 participants were included in the analyses.

Analyses identified 5 general patterns of partnership history: stable marriage (a brief period of dating followed by a permanent first marriage), being remarried (getting married in their 20s and divorcing within the first 10 years, only to remarry in their 30s, with later marriages often preceded by cohabitation), divorce (the same as the previous one, but without a remarriage), serial cohabitation (dating and cohabiting prominent throughout the life course), and single (individuals who never lived with a partner, and many of whom never dated).

Most of the participants were in the stable marriage category, while the singles and serial cohabitation patterns were the rarest. Men were more frequent in the single category, while women were more frequent in the divorce category.

Further analysis revealed that individuals in the stable marriage category enjoyed greater well-being compared to all the other categories. This difference was present across all education levels. However, those with lower education who have divorced experienced even lower well-being in old age. Overall, results indicate that those with fewer resources tend to suffer more from losing a partner.

Study authors conclude that “…life courses characterized by stable marriages tend to be coupled with good health and high quality of life, unstable and single histories less so. Low educational attainment together with partnership trajectories characterized by divorce have pronounced adverse well-being associations. Our results hint at family formation patterns that may foster well-being and mechanisms that potentially boost or buffer the outcomes.”

The study sheds light on the links between romantic relationship patterns and well-being in old age. However, it should be noted that the study exclusively included individuals from the baby boomer generation. Given pronounced cultural differences between generations in the past century, results on people from other generations might not be identical.

The paper, “Stable Marital Histories Predict Happiness and Health Across Educational Groups,” was authored by Miika Mäki, Anna Erika Hägglund, Anna Rotkirch, Sangita Kulathinal, and Mikko Myrskylä.

A single dose made tumors disappear completely in mice.

A single dose made tumors disappear completely in mice.

A new study suggests that body shape, specifically the degree of roundness around the abdomen, may help predict the risk of developing depression. Researchers found that individuals with a higher Body Roundness Index faced a higher likelihood of being diagnosed with this mental health condition over time. These findings were published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

Depression is a widespread mental health challenge that affects roughly 300 million people globally. It often brings severe physical health burdens and economic costs to individuals and society. Medical professionals have identified obesity as a potential risk factor for mental health issues. The standard tool for measuring obesity is the Body Mass Index, or BMI. This metric calculates a score based solely on a person’s weight and height.

However, the Body Mass Index has limitations regarding accuracy in assessing health risks. It cannot distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass. It also fails to indicate where fat is stored on the body. This distinction is vital because fat stored around the abdomen is often more metabolically harmful than fat stored elsewhere. To address these gaps, scientists developed the Body Roundness Index.

This newer metric uses waist circumference in relation to height to estimate the amount of visceral fat a person carries. Visceral fat is the fat stored deep inside the abdomen, wrapping around internal organs. This type of fat is biologically active and linked to various chronic diseases. Previous research hinted at a connection between this type of fat and mental health, but long-term data was limited.

Yinghong Zhai from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine served as a lead author on this new project. Zhai and colleagues sought to clarify if body roundness could predict future depression better than general weight measures. They also wanted to understand if lifestyle choices like smoking or exercise explained the connection.

To investigate this, the team utilized data from the UK Biobank. This is a massive biomedical database containing genetic, health, and lifestyle information from residents of the United Kingdom. The researchers selected records for 201,813 adults who did not have a diagnosis of depression when they joined the biobank. Participants ranged in age from 40 to 69 years old at the start of the data collection.

The researchers calculated the Body Roundness Index for each person using their waist and height measurements. They then tracked these individuals for an average of nearly 13 years. The goal was to see which participants developed new cases of depression during that decade. To ensure accuracy, the analysis accounted for various influencing factors.

These factors included age, biological sex, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity. The team also controlled for existing health conditions like type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. They further adjusted for lifestyle habits, such as alcohol consumption and sleep duration. The results showed a clear pattern linking body shape to mental health outcomes.

Participants were divided into four groups, or quartiles, based on their body roundness scores. Those in the highest quartile had the largest waist-to-height ratios. The analysis showed that these individuals had a 30 percent higher risk of developing depression compared to those in the lowest quartile. This association held true even after the researchers adjusted for traditional Body Mass Index scores.

The relationship appeared to follow a “J-shaped” curve. This means that as body roundness increased, the probability of a depression diagnosis rose progressively. The trend was consistent across different subgroups of people. It affected both men and women, as well as people older and younger than 60.

The team also investigated the role of lifestyle behaviors in this relationship. They used statistical mediation analysis to see if habits like smoking or drinking explained the link. The question was whether body roundness led to specific behaviors that then caused depression. They found that smoking status did contribute to the increased risk.

Conversely, physical activity offered a protective effect, slightly lowering the risk. Education levels also played a minor mediating role. However, these lifestyle factors only explained a small portion of the overall connection. The direct link between body roundness and depression remained robust regardless of these behaviors.

The authors discussed potential biological mechanisms that might explain why central obesity correlates with mood disorders. Abdominal fat acts somewhat like an active organ. It releases inflammatory markers, such as cytokines, into the bloodstream. These markers can cross the blood-brain barrier. Once in the brain, they may disrupt the function of neurotransmitters that regulate mood.

Another possibility involves hormonal imbalances. Obesity is often associated with resistance to leptin, a hormone that regulates energy balance. High levels of leptin can interfere with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. This axis is a complex system of neuroendocrine pathways that controls the body’s reaction to stress. Disruption here is a known feature of depression.

The study also considered the social and psychological aspects of body image. While the biological links are strong, the authors noted that societal stigma could play a role. However, the persistence of the link after adjusting for many social factors points toward a physiological connection.

While the study involved a large number of people, it has specific limitations. The majority of participants in the UK Biobank are of white European descent. This lack of diversity means the results might not apply directly to other ethnic groups. The authors advise caution when generalizing these findings to diverse populations.

Additionally, the study is observational rather than experimental. This design means researchers can identify a correlation but cannot definitively prove that body roundness causes depression. There is also the possibility of unmeasured factors influencing the results. For example, changes in body weight or mental health status over the 13-year period were not fully tracked day-to-day.

The researchers also noted that they did not compare the predictive power of the Body Roundness Index against other metrics directly in a competition. They focused on establishing the link between this specific index and depression. Future research would need to validate how this tool performs against others in clinical settings.

The authors suggest that future research should focus on more diverse populations to confirm these trends. They also recommend investigating the specific biological pathways that connect abdominal fat to brain function more deeply. Understanding the role of inflammation and hormones could lead to better treatments.

If confirmed, these results could help doctors use simple body measurements as a screening tool. It highlights the potential mental health benefits of managing central obesity. By monitoring body roundness, healthcare providers might identify individuals at higher risk for depression earlier. This could allow for earlier interventions regarding lifestyle or mental health support.

The study, “Body roundness index, depression, and the mediating role of lifestyle: Insights from the UK biobank cohort,” was authored by Yinghong Zhai, Fangyuan Hu, Yang Cao, Run Du, Chao Xue, and Feng Xu.

New research provides evidence that men who are concerned about maintaining a traditional masculine image may be less likely to express concern about climate change. The findings suggest that acknowledging environmental problems is psychologically linked to traits such as warmth and compassion. These traits are stereotypically associated with femininity in many cultures. Consequently, men who feel pressure to prove their manhood may avoid environmentalist attitudes to protect their gender identity. The study was published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology.

Scientific consensus indicates that climate change is occurring and poses significant risks to global stability. Despite this evidence, public opinion remains divided. Surveys consistently reveal a gender gap regarding environmental attitudes. Men typically express less concern about climate change than women do. Michael P. Haselhuhn, a researcher at the University of California, Riverside, sought to understand the psychological drivers behind this disparity.

Haselhuhn conducted this research to investigate why within-gender differences exist regarding climate views. Past studies have often focused on political ideology or a lack of scientific knowledge as primary explanations. Haselhuhn proposed that the motivation to adhere to gender norms plays a significant but overlooked role. He based his hypothesis on the theory of precarious manhood.

Precarious manhood theory posits that manhood is viewed socially as a status that is difficult to earn and easy to lose. Unlike womanhood, which is often treated as a biological inevitability, manhood must be proven through action. This psychological framework suggests that men experience anxiety about failing to meet societal standards of masculinity. They must constant reinforce their status and avoid behaviors that appear feminine.

Socialization often expects women to be communal, caring, and warm. In contrast, men are often expected to be agentic, tough, and emotionally reserved. Haselhuhn theorized that because caring for the environment involves communal concern, it signals warmth. Men who are anxious about their social status might perceive this signal as a threat. They may reject climate science not because they misunderstand the data, but because they wish to avoid seeming “soft.”

The researcher began with a preliminary test to establish whether environmental concern is indeed viewed as a feminine trait. He recruited 450 participants from the United States through an online platform. These participants read a short scenario about a male university student named Adam. Adam was described as an undergraduate majoring in Economics who enjoyed running.

In the control condition, Adam was described as active in general student issues. In the experimental condition, Adam was described as concerned about climate change and active in a “Save the Planet” group. After reading the scenario, participants rated Adam on various personality traits. Haselhuhn specifically looked at ratings for warmth, caring, and compassion.

The results showed that when Adam was described as concerned about climate change, he was perceived as significantly warmer than when he was interested in general student issues. Participants viewed the environmentalist version of Adam as possessing more traditionally feminine character traits. This initial test confirmed that expressing environmental concern can alter how a man’s gender presentation is perceived by others.

Following this pretest, Haselhuhn analyzed data from the European Social Survey to test the hypothesis on a large scale. This survey included responses from 40,156 individuals across multiple European nations. The survey provided a diverse sample that allowed the researcher to look for broad patterns in the general population.

The survey asked participants to rate how important “being a man” was to their self-concept if they were male. It asked women the same regarding “being a woman.” It also measured three specific climate attitudes. These included belief in human causation, feelings of personal responsibility, and overall worry about climate change.

Haselhuhn found a negative relationship between masculinity concerns and climate engagement. Men who placed a high importance on being a man were less likely to believe that climate change is caused by human activity. They also reported feeling less personal responsibility to reduce climate change. Furthermore, these men expressed lower levels of worry about the issue.

A similar pattern appeared for women regarding the importance of being a woman. However, statistical analysis confirmed that the effect of gender role concern on climate attitudes was significantly stronger for men. This aligns with the theory that the pressure to maintain one’s gender status is more acute for men due to the precarious nature of manhood.

To validate these findings with more precise psychological tools, Haselhuhn conducted a second study with 401 adults in the United States. The measure used in the European survey was a single question, which might have lacked nuance. In this second study, men completed the Masculine Gender Role Stress scale.

This scale assesses how much anxiety men feel in situations that challenge traditional masculinity. Items include situations such as losing in a sports competition or admitting fear. Women completed a parallel scale regarding feminine gender stress. This scale includes items about trying to excel at work while being a good parent. Climate attitudes were measured using a standard scale assessing conviction that climate change is real and concern about its impact.

The results from the second study replicated the findings from the large-scale survey. Men who scored higher on masculinity stress expressed significantly less concern about climate change. This relationship held true regardless of the participants’ political orientation. Haselhuhn found no relationship between gender role stress and climate attitudes among women in this sample. This suggests that the pressure to adhere to gender norms specifically discourages men from engaging with environmental issues.

A third study was conducted to pinpoint the underlying mechanism. Haselhuhn recruited 482 men from the United States for this final experiment. He sought to confirm that the fear of appearing “warm” or feminine was the specific driver of the effect. Participants completed the same masculinity stress scale and climate attitude measures used in the previous study.

They also completed a task where they categorized various personality traits. Participants rated whether traits such as “warm,” “tolerant,” and “sincere” were expected to be more characteristic of men or women. This allowed the researcher to see how strongly each participant associated warmth with femininity.

Haselhuhn found that men with high masculinity concerns were generally less concerned about climate change. However, this effect depended on their beliefs about warmth. The negative relationship between masculinity concerns and climate attitudes was strongest among men who viewed warmth as a distinctly feminine characteristic.

For men who did not strongly associate warmth with women, the pressure to be masculine did not strongly predict their views on climate change. This provides evidence that the avoidance of feminine stereotypes is a key reason why insecure men distance themselves from environmentalism. They appear to regulate their attitudes to avoid signaling traits that society assigns to women.

These findings have implications for how climate change communication is framed. If environmentalism is perceived as an act of caring and compassion, it may continue to alienate men who are anxious about their gender status. Haselhuhn notes that the effect sizes in the study were small but consistent. This means that while gender concerns are not the only factor driving climate denial, they are a measurable contributor.

The study has some limitations. It relied on self-reported attitudes rather than observable behaviors. It is possible that the pressure to conform to masculine norms would be even higher in public settings where men are watched by peers. Men might be willing to express concern in an anonymous survey but reject those views in a group setting to maintain status.

Future research could examine whether reframing environmental action affects these attitudes. Describing climate action in terms of protection, courage, or duty might make the issue more palatable to men with high masculinity concerns. Additionally, future work could investigate whether affirming a man’s masculinity in other ways reduces his need to reject environmental concern. The current data indicates that for many men, the desire to be seen as a “real man” conflicts with the desire to save the planet.

The study, “Man enough to save the planet? Masculinity concerns predict attitudes toward climate change,” was authored by Michael P. Haselhuhn.

New research indicates that perceiving one’s social group as possessing inner spiritual strength can drive members to extreme acts of self-sacrifice. This willingness to suffer for the group appears to be fueled by collective narcissism, a belief that the group is exceptional but underappreciated by others. The findings suggest that narratives of spiritual power may inadvertently foster dangerous forms of group entitlement. The study was published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

History is replete with examples of smaller groups overcoming larger adversaries through sheer willpower. Social psychologists have termed this perceived inner strength “spiritual formidability.” This concept refers to the conviction in a cause and the resolve to pursue it regardless of material disadvantages. Previous observations of combatants in conflict zones have shown that spiritual formidability is often a better predictor of the willingness to fight than physical strength or weaponry.

The authors of the current study sought to understand the psychological mechanisms behind this phenomenon. They aimed to determine why a perception of spiritual strength translates into a readiness to die or suffer for a group. They hypothesized that this process is not merely a result of loyalty or love for the group. Instead, they proposed that it stems from a demand for symbolic recognition.

The researchers suspected that viewing one’s group as spiritually powerful feeds into collective narcissism. Collective narcissism differs from simple group pride or satisfaction. It involves a defensive form of attachment where members believe their group possesses an undervalued greatness that requires external validation. The study tested whether this specific type of narcissistic belief acts as the bridge between spiritual formidability and self-sacrifice.

“Previous research has shown that perceiving one’s group as spiritually strong—deeply committed to its values—predicts a willingness to fight and self-sacrifice, but the psychological mechanisms behind this link were still unclear,” said study author Juana Chinchilla, an assistant professor of social psychology at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) in Spain.

“We were particularly interested in understanding why narratives of moral or spiritual strength can motivate extreme sacrifices, especially in real-world contexts marked by conflict and behavioral radicalization. This study addresses that gap by identifying collective narcissism as a key mechanism connecting spiritual formidability to extreme self-sacrificial intentions.”

The research team conducted a series of five investigations to test their hypothesis. They began with a preliminary online survey of 420 individuals from the general population in Spain. Participants completed measures assessing their satisfaction with their nation and their levels of national collective narcissism. They also rated their willingness to engage in extreme actions to defend the country, such as going to jail or dying.

A central component of this preliminary study was the inclusion of ingroup satisfaction as a control variable. Ingroup satisfaction represents a secure sense of pride and happiness with one’s membership in a group. It is distinct from the defensive and resentful nature of collective narcissism. By statistically controlling for this variable, the researchers aimed to isolate the specific effects of narcissism.

The data from this initial survey provided a baseline for the researchers’ theory. The results showed that collective narcissism predicted a willingness to sacrifice for the country even after accounting for the influence of ingroup satisfaction.

“One striking finding was how reliably collective narcissism explained self-sacrificial intentions even when controlling for more secure forms of group attachment, such as ingroup satisfaction,” Chinchilla told PsyPost. “This suggests that extreme sacrifice is not always driven by genuine concern for the group’s well-being, but sometimes by defensive beliefs about the group’s greatness and lack of recognition. We were also surprised by how easily these processes could be activated through shared narratives about spiritual strength.”

Following this preliminary work, the researchers gained access to high-security penitentiary centers across Spain for two field studies. Study 1a involved 70 male inmates convicted of crimes related to membership in violent street gangs. Study 1b focused on 47 male inmates imprisoned for organized property crimes and membership in delinquent bands. These populations were selected because they are known for engaging in costly actions to protect their groups.

In these prison studies, participants used a dynamic visual measure to rate their group’s spiritual formidability. They were shown an image of a human body and adjusted a slider to change its size and muscularity. This visual metaphor represented the inner strength and conviction of their specific gang or band. They also completed questionnaires measuring collective narcissism and their willingness to make sacrifices, such as enduring longer prison sentences or cutting off family contact.

The findings from the prison samples were consistent with the initial hypothesis. Inmates who perceived their gang or band as spiritually formidable reported higher levels of collective narcissism. This sense of underappreciated greatness was statistically associated with a higher willingness to make severe personal sacrifices. Mediation analysis indicated that collective narcissism explains why spiritual formidability leads to self-sacrifice.

The researchers then extended their investigation to a sample of 88 inmates convicted of jihadist terrorism or proselytizing in prison. This sample included individuals involved in major attacks and thwarted plots. The procedure mirrored the previous studies but focused on the broader ideological group of Muslims rather than a specific criminal band. Participants rated the spiritual formidability of Muslims and their willingness to sacrifice for their religious ideology.

The researchers conducted additional statistical analyses to ensure the robustness of these findings. These models explicitly controlled for the gender of the participants. This step ensured that the observed effects were not simply due to differences in how men and women might approach sacrifice or group perception.

The results from the jihadist sample aligned with those from the street gangs. Perceptions of spiritual strength within the religious community were associated with higher collective narcissism regarding the faith. This defensive pride predicted a greater readiness to suffer for the ideology. The relationship remained significant even when controlling for gender. The study demonstrated that the psychological mechanism operates for large-scale ideological values just as it does for small, cohesive gangs.

Finally, the researchers conducted an experimental study with 457 Spanish citizens to establish causality. This study took place during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, a time of heightened threat and social uncertainty. The researchers provided false feedback to a portion of the participants. This feedback stated that most Spaniards viewed their country as possessing high spiritual formidability.

Participants in the control group received no information regarding how other citizens viewed the nation. All participants then completed measures of collective narcissism and willingness to sacrifice to defend the country against the pandemic. The manipulation was designed to test if simply hearing about the group’s spiritual strength would trigger the proposed psychological chain reaction.

The experiment confirmed the causal role of spiritual formidability. Participants led to believe their country was spiritually formidable scored higher on measures of collective narcissism. They also expressed a greater willingness to endure extreme hardships to fight the pandemic. Statistical analysis confirmed that the manipulation influenced self-sacrifice specifically by boosting collective narcissism.

The study provides evidence that narratives of spiritual strength can have a double-edged nature. While such beliefs can foster cohesion, they can also trigger a sense of entitlement and resentment toward those who do not recognize the group’s greatness. This defensive mindset appears to be a key driver of extreme pro-group behavior.

“Our findings suggest that believing one’s group is spiritually formidable can motivate extreme self-sacrifice not only through loyalty or love, but also through a sense that the group is undervalued and deserves greater recognition,” Chinchilla explained. “This illustrates that people may engage in risky or extreme progroup actions to achieve symbolic recognition. Importantly, it also highlights how seemingly positive narratives about spiritual strength can have unintended and potentially dangerous consequences.”

However, “it would be a mistake to interpret spiritual formidability as inherently dangerous or as a direct cause of violence. On its own, perceiving the ingroup as morally committed and spiritually strong can promote loyalty, trust, and cohesion. The problematic consequences may arise only under severe threat or when perceptions of spiritual formidability become intertwined with collective narcissism.”

Future research is needed to determine when exactly these beliefs turn into narcissistic entitlement. The authors note that a key challenge is clarifying the boundary conditions under which spiritual formidability gives rise to collective narcissism. This distinction might depend on whether individuals see violence as morally acceptable.

“We plan to examine whether similar mechanisms operate in non-violent movements, such as environmental or human rights activism, where strong moral commitment is critical,” Chinchilla said. “Another important next step is identifying interventions that can decouple spiritual formidability from collective narcissism, for example by promoting narratives that frame cooperation and peace as markers of true moral strength.”

“One of the strengths of this research is the diversity of the samples, including populations that are rarely accessible in psychological research. Studying these processes in real-world, high-stakes contexts helps bridge the gap between laboratory findings and the dynamics underlying radicalization, intergroup conflict, and extreme collective behavior.”

The study, “Spiritual Formidability Predicts the Will to Self-Sacrifice Through Collective Narcissism,” was authored by Juana Chinchilla and Angel Gomez.

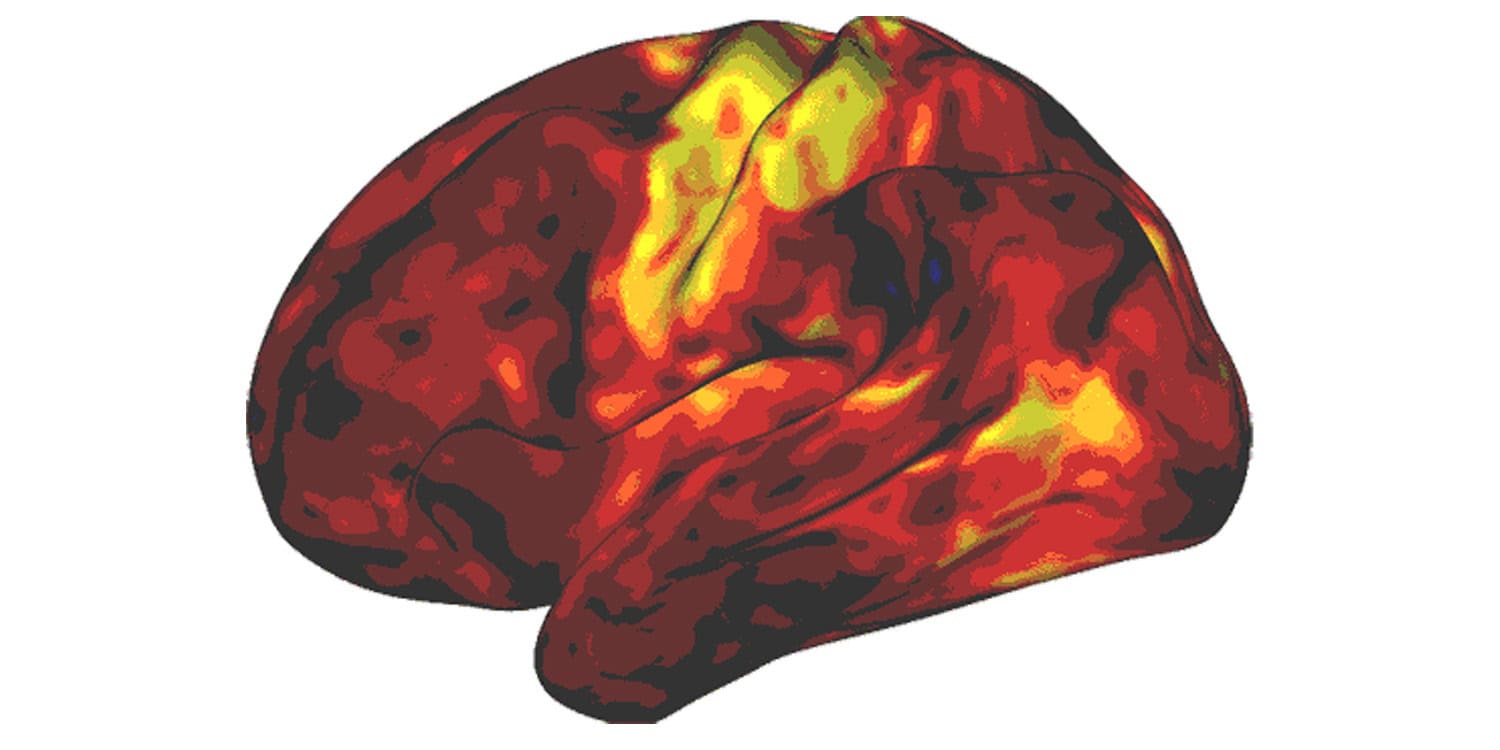

Recent research has identified specific patterns of brain activity that distinguish young children with autism from their typically developing peers. These patterns involve the way different regions of the brain communicate with one another over time and appear to be directly linked to the severity of autism symptoms. The findings suggest that these neural dynamics influence daily adaptive skills, which in turn affect cognitive performance. The study was published in The Journal of Neuroscience.