Scientists achieve full neurological recovery from Alzheimer’s in mice by restoring metabolic balance

Researchers have discovered that Alzheimer’s disease may be reversible in animal models through a treatment that restores the brain’s metabolic balance. This study, published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, demonstrates that restoring levels of a specific energy molecule allows the brain to repair damage and recover cognitive function even in advanced stages of the illness. The results suggest that the cognitive decline associated with the condition is not an inevitable permanent state but rather a result of a loss of brain resilience.

For more than a century, people have considered Alzheimer’s disease an irreversible illness. Consequently, research has focused on preventing or slowing it, rather than recovery. Despite billions of dollars spent on decades of research, there has never been a clinical trial of any drug to reverse and recover from the condition. This new research challenges that long held dogma.

The study was led by Kalyani Chaubey, a researcher at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. She worked alongside senior author Andrew A. Pieper, who is a professor at Case Western Reserve and director of the Brain Health Medicines Center at Harrington Discovery Institute. The team included scientists from University Hospitals and the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center.

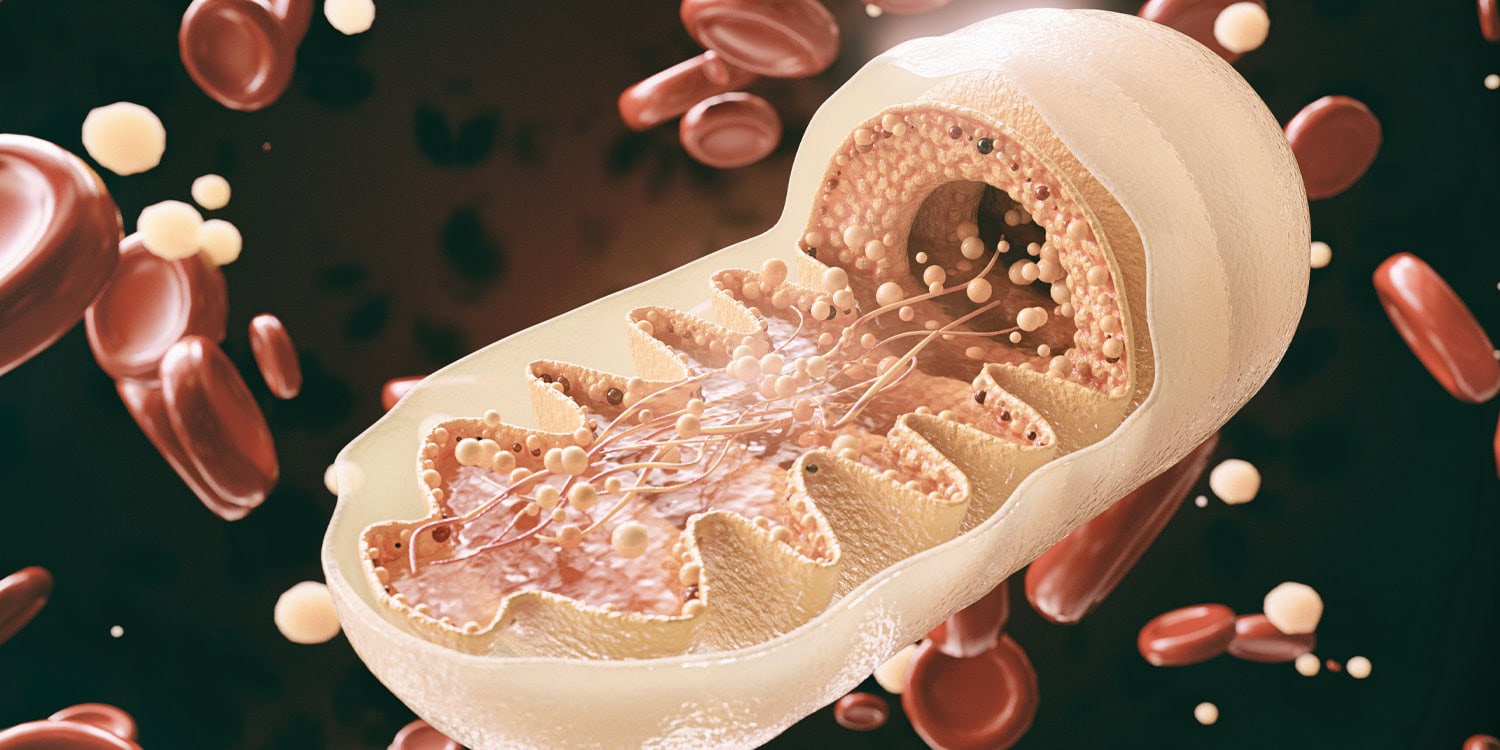

The researchers focused on a molecule called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, known as NAD+. This molecule is essential for cellular energy and repair across the entire body. Scientists have observed that NAD+ levels decline naturally as people age, but this loss is much more pronounced in those with neurodegenerative conditions. Without proper levels of this metabolic currency, cells become unable to execute the processes required for proper functioning and survival.

Previous research has established a foundation for this approach. A 2018 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that supplementing with NAD+ precursors could normalize neuroinflammation and DNA damage in mice. That earlier work suggested that a depletion of this molecule sits upstream of many other symptoms like tau protein buildup and synaptic dysfunction.

In 2021, another study published in the same journal found that restoring this energy balance could reduce cell senescence, which is a state where cells stop dividing but do not die. This process is linked to the chronic inflammation seen in aging brains.

Additionally, an international team led by researchers at the University of Oslo recently identified a mechanism where NAD+ helps correct errors in how brain cells process genetic information. That study, published in Science Advances, identified a specific protein called EVA1C as a central player in helping the brain manage damaged proteins.

Despite these promising leads, many existing supplements can push NAD+ to supraphysiologic levels. High levels that exceed what is natural for the body have been linked to an increased risk of cancer in some animal models. The Case Western Reserve team wanted to find a way to restore balance without overshooting the natural range.

They utilized a compound called P7C3-A20, which was originally developed in the Pieper laboratory. This compound is a neuroprotective agent that helps cells maintain their proper balance of NAD+ under conditions of overwhelming stress. It does not elevate the molecule to levels that are unnaturally high.

To test the potential for reversal, the researchers used two distinct mouse models. The first, known as 5xFAD, is designed to develop heavy amyloid plaque buildup and human like tau changes. The second model, PS19, carries a human mutation in the tau protein that causes toxic tangles and the death of neurons. These models allow scientists to study the major biological hallmarks of the human disease.

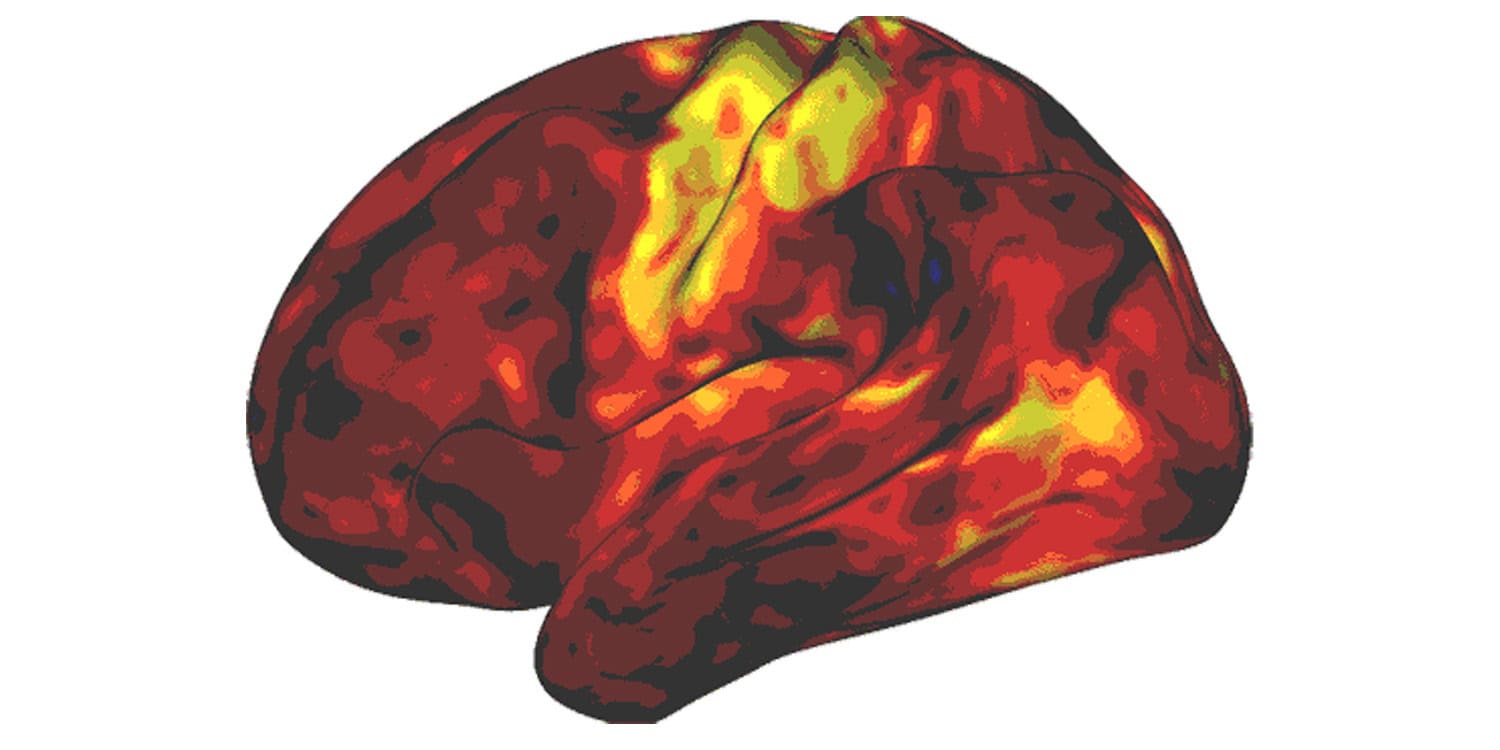

The researchers first confirmed that brain energy balance deteriorates as the disease progresses. In mice that were two months old and pre-symptomatic, NAD+ levels were normal. By six months, when the mice showed clear signs of cognitive trouble, their levels had dropped by 30 percent. By twelve months, when the disease was very advanced, the deficit reached 45 percent.

The core of the study involved a group of mice designated as the advanced disease stage cohort. These animals did not begin treatment until they were six months old. At this point, they already possessed established brain pathology and measurable cognitive decline. They received daily injections of the treatment until they reached one year of age.

The results showed a comprehensive recovery of function. In memory tests like the Morris water maze, where mice must remember the location of a submerged platform, the treated animals performed as well as healthy controls. Their spatial learning and memory were restored to normal levels despite their genetic mutations.

The mice also showed improvements in physical coordination. On a rotating rod test, which measures motor learning, the advanced stage mice regained their ability to balance and stay on the device. Their performance was not statistically different from healthy mice by the end of the treatment period.

The biological changes inside the brain were equally notable. The treatment repaired the blood brain barrier, which is the protective seal around the brain’s blood vessels. In Alzheimer’s disease, this barrier often develops leaks that allow harmful substances into the brain tissue. Electronic microscope images showed that the treatment had sealed these gaps and restored the health of supporting cells called pericytes.

The researchers also tracked a specific marker called p-tau217. This is a form of the tau protein that is now used as a standard clinical biomarker in human patients. The team found that levels of this marker in the blood were reduced by the treatment. This finding provides an objective way to confirm that the disease was being reversed.

Speaking about the discovery, Pieper noted the importance of the results for future medicine. “We were very excited and encouraged by our results,” he said. “Restoring the brain’s energy balance achieved pathological and functional recovery in both lines of mice with advanced Alzheimer’s. Seeing this effect in two very different animal models, each driven by different genetic causes, strengthens the new idea that recovery from advanced disease might be possible in people with AD when the brain’s NAD+ balance is restored.”

The team also performed a proteomic analysis, which is a massive screen of all the proteins in the brain. They identified 46 specific proteins that are altered in the same way in both human patients and the sick mice. These proteins are involved in tasks like waste management, protein folding, and mitochondrial function. The treatment successfully returned these protein levels to their healthy state.

To ensure the mouse findings were relevant to humans, the scientists studied a unique group of people. These individuals are known as nondemented with Alzheimer’s neuropathology. Their brains are full of amyloid plaques, yet they remained cognitively healthy throughout their lives. The researchers found that these resilient individuals naturally possessed higher levels of the enzymes that produce NAD+.

This human data suggests that the brain has an intrinsic ability to resist damage if its energy balance remains intact. The treatment appears to mimic this natural resilience. “The damaged brain can, under some conditions, repair itself and regain function,” Pieper explained. He emphasized that the takeaway from this work is a message of hope.

The study also included tests on human brain microvascular endothelial cells. These are the cells that make up the blood brain barrier in people. When these cells were exposed to oxidative stress in the laboratory, the treatment protected them from damage. It helped their mitochondria continue to produce energy and prevented the cells from dying.

While the results are promising, there are some limitations to the study. The researchers relied on genetic mouse models, which represent the rare inherited forms of the disease. Most people suffer from the sporadic form of the condition, which may have more varied causes. Additionally, human brain samples used for comparison represent a single moment in time, which makes it difficult to establish a clear cause and effect relationship.

Future research will focus on moving this approach into human clinical trials. The scientists want to determine if the efficacy seen in mice will translate to human patients. They also hope to identify which specific aspects of the brain’s energy balance are the most important for starting the recovery process.

The technology is currently being commercialized by a company called Glengary Brain Health. The goal is to develop a therapy that could one day be used to treat patients who already show signs of cognitive loss. As Chaubey noted, “Through our study, we demonstrated one drug-based way to accomplish this in animal models, and also identified candidate proteins in the human AD brain that may relate to the ability to reverse AD.”

The study, “Pharmacologic reversal of advanced Alzheimer’s disease in mice and identification of potential therapeutic nodes in human brain,” was authored by Kalyani Chaubey, Edwin Vázquez-Rosa, Sunil Jamuna Tripathi, Min-Kyoo Shin, Youngmin Yu, Matasha Dhar, Suwarna Chakraborty, Mai Yamakawa, Xinming Wang, Preethy S. Sridharan, Emiko Miller, Zea Bud, Sofia G. Corella, Sarah Barker, Salvatore G. Caradonna, Yeojung Koh, Kathryn Franke, Coral J. Cintrón-Pérez, Sophia Rose, Hua Fang, Adrian A. Cintrón-Pérez, Taylor Tomco, Xiongwei Zhu, Hisashi Fujioka, Tamar Gefen, Margaret E. Flanagan, Noelle S. Williams, Brigid M. Wilson, Lawrence Chen, Lijun Dou, Feixiong Cheng, Jessica E. Rexach, Jung-A Woo, David E. Kang, Bindu D. Paul, and Andrew A. Pieper.