Alcohol shifts the brain into a fragmented and local state

A standard glass of wine or beer does more than just relax the body; it fundamentally alters the landscape of communication within the brain. New research suggests that acute alcohol consumption shifts neural activity from a flexible, globally integrated network to a more segmented, local structure. These changes in brain architecture appear to track with how intoxicated a person feels. The findings were published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

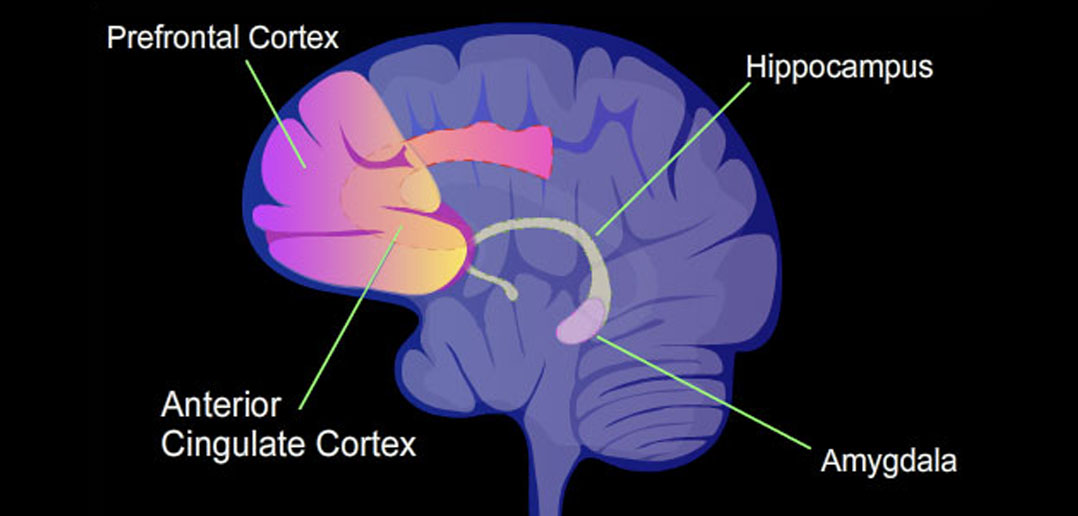

For decades, neuroscientists have worked to map how alcohol affects human behavior. Traditional studies often look at specific brain regions in isolation. Researchers might observe that activity in the prefrontal cortex dampens, which explains why inhibition lowers. Alternatively, they might see changes in the cerebellum, which accounts for the loss of physical coordination.

However, the brain does not operate as a collection of independent islands. It functions as a massive, interconnected web. Information must travel constantly between different areas to process sights, sounds, and thoughts. Understanding how alcohol impacts the traffic patterns of this web requires a different mathematical approach known as graph theory.

Graph theory allows scientists to treat the brain like a vast map of cities and highways. The “cities” are distinct brain regions, referred to as nodes. The “highways” are the functional connections between them, known as edges. By analyzing the flow of traffic across these highways, researchers can determine how efficiently the brain is sharing information.

Leah A. Biessenberger and her colleagues at the University of Minnesota and the University of Florida sought to apply this network-level analysis to social drinkers. Biessenberger, the study’s lead author, worked alongside senior author Jeff Boissoneault and a wider team. They aimed to fill a gap in the scientific literature regarding acute alcohol use.

While previous research has examined how chronic, heavy drinking reshapes the brain over years, less is known about the immediate network effects of a single drinking session. The researchers wanted to observe the brain in a “resting state.” This is the baseline activity that occurs when a person is awake but not performing a specific task.

To investigate this, the team recruited 107 healthy adults between the ages of 21 and 45. The participants were social drinkers without a history of alcohol use disorder. The study utilized a double-blind, placebo-controlled design. This method is the gold standard for removing bias from clinical experiments.

Each participant visited the laboratory for two separate sessions. During one visit, they consumed a beverage containing alcohol mixed with a sugar-free mixer. The dose was calculated to bring their breath alcohol concentration to 0.08 grams per deciliter, which is the legal driving limit in the United States.

During the other visit, they received a placebo drink. This beverage contained only the mixer but was misted with a small amount of alcohol on the surface and rim to mimic the smell and taste of a real cocktail. Neither the participants nor the research staff knew which drink was administered on a given day.

Approximately 30 minutes after drinking, the participants entered an MRI scanner. They were instructed to keep their eyes open and let their minds wander. The scanner recorded the blood oxygen levels in their brains, which serves as a proxy for neural activity.

The researchers then used computational tools to analyze the functional connectivity between 106 different brain regions. They looked for specific patterns in the data described by graph theory metrics. These metrics included “global efficiency” and “local efficiency.”

Global efficiency measures how easily information travels across the entire network. A network with high global efficiency has many long-distance shortcuts, allowing distant regions to communicate quickly. Local efficiency measures how well neighbors talk to neighbors. It reflects the tendency of brain regions to form tight-knit clusters that process information among themselves.

The analysis revealed distinct shifts in the brain’s topology following alcohol consumption. When participants drank alcohol, their brains moved toward a more “grid-like” state. The network became less random and more clustered.

Specifically, the study found that global efficiency decreased in several areas. This was particularly evident in the occipital lobe, the part of the brain responsible for processing vision. The reduction suggests that alcohol makes it harder for visual information to integrate with the rest of the brain’s operations.

Simultaneously, local efficiency increased. Regions in the frontal and temporal cortices began to communicate more intensely with their immediate neighbors. The brain appeared to fracture into smaller, self-contained communities. This structure requires less energy to maintain but hinders the rapid integration of complex information.

The researchers also examined a metric called “clustering coefficient.” This value reflects the likelihood that a node’s neighbors are also connected to each other. Alcohol increased the clustering coefficient across the network. This further supports the idea that the intoxicated brain relies more on local processing than global integration.

The team also looked at the “insula,” a region deeply involved in sensing the body’s internal state. Under the influence of alcohol, the insula showed increased connections with its local neighbors. It also displayed greater activity in communicating with the broader network compared to the placebo condition.

These architectural changes were not merely abstract mathematical observations. The researchers found a statistical link between the network shifts and the participants’ subjective experiences. Before the scan, participants rated how intoxicated they felt on a scale of 0 to 100.

The results showed that the degree of network reorganization predicted the intensity of the subjective “buzz.” Participants whose brains showed the largest drop in global efficiency and the largest rise in local clustering tended to report feeling the most intoxicated. The structural breakdown of long-range communication tracked with the feeling of impairment.

This correlation offers new insight into why individuals react differently to the same amount of alcohol. Even at the same blood alcohol concentration, people experience varying levels of intoxication. The study suggests that individual differences in how the brain network fragments may underlie these varying subjective responses.

The findings also highlighted disruptions in the visual system. The decrease in efficiency within the occipital regions was marked. This aligns with well-known effects of drunkenness, such as blurred vision or difficulty tracking moving objects. The network analysis provides a neural basis for these sensory deficits.

While the study offers robust evidence, the authors note certain limitations. The MRI scans did not capture the cerebellum consistently for all participants. The cerebellum is vital for balance and motor control. Because it was not included in the analysis, the picture of alcohol’s effect on the whole brain remains incomplete.

Additionally, the study focused on young, healthy adults. The brain changes observed here might differ in older adults or individuals with a history of substance abuse. Aging brains already show some reductions in global efficiency. Alcohol could compound these effects in older populations.

The researchers also point out that the participants were in a resting state. The brain rearranges its network when actively solving problems or processing emotions. Future research will need to determine if these topological shifts persist or worsen when an intoxicated person tries to perform a complex task, like driving.

This investigation provides a nuanced view of acute intoxication. It moves beyond the idea that alcohol simply “dampens” brain activity. Instead, it reveals that alcohol forces the brain into a segregated state. Information gets trapped in local cul-de-sacs rather than traveling the superhighways of the mind.

By connecting these mathematical patterns to the subjective feeling of being drunk, the study helps bridge the gap between biology and behavior. It illustrates that the sensation of intoxication is, in part, the feeling of a brain losing its global coherence.

The study, “Acute alcohol intake disrupts resting state network topology in healthy social drinkers,” was authored by Leah A. Biessenberger, Adriana K. Cushnie, Bethany Stennett-Blackmon, Landrew S. Sevel, Michael E. Robinson, Sara Jo Nixon, and Jeff Boissoneault.