Brain scans reveal neural connectivity deficits in Long COVID and ME/CFS

New research suggests that the brains of people with Long COVID and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) struggle to communicate effectively during mentally tiring tasks. While healthy brains appear to tighten their neural connections when fatigued, these patients show disrupted or weakened signals between key brain areas. This study was published in the Journal of Translational Medicine.

ME/CFS and Long COVID are chronic conditions that severely impact the quality of life for millions of people. Patients often experience extreme exhaustion and “brain fog,” which refers to persistent difficulties with memory and concentration.

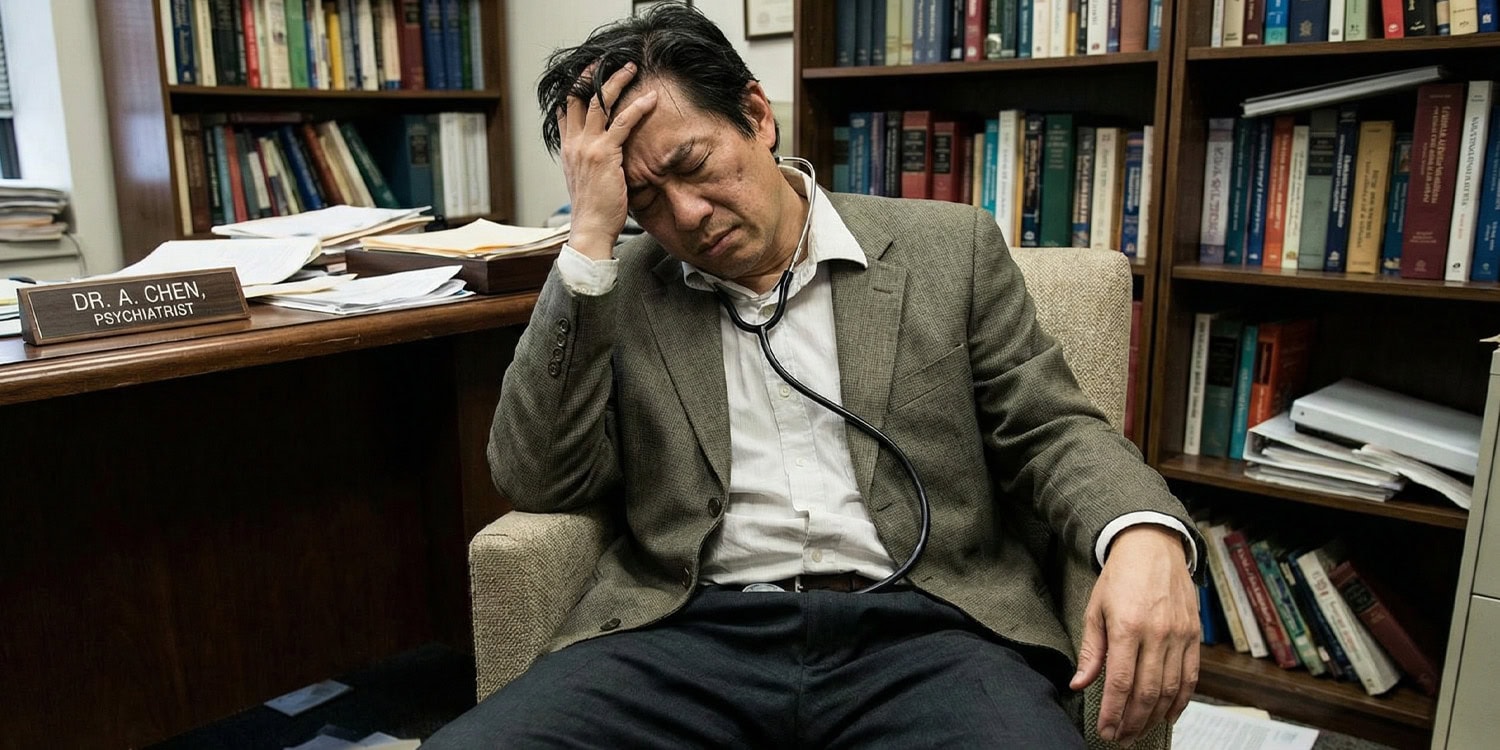

A defining feature of these illnesses is post-exertional malaise. This describes a crash in energy and a worsening of symptoms that follows even minor physical or mental effort. Doctors currently lack a definitive biological test to diagnose these conditions. This makes it difficult to distinguish them from one another or from other disorders with similar symptoms.

The research team sought to identify objective biological markers of these illnesses. Maira Inderyas, a PhD candidate at the National Centre for Neuroimmunology and Emerging Diseases at Griffith University in Australia, led the investigation. She worked alongside senior researchers including Professor Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik. They aimed to understand how the brain behaves when pushed to the limit of its cognitive endurance.

Professor Marshall-Gradisnik noted the shared experiences of these patient groups. “The symptoms include cognitive difficulties, such as memory problems, difficulties with attention and concentration, and slowed thinking,” Professor Marshall-Gradisnik said. The team hypothesized that these subjective feelings of brain fog would correspond to visible changes in brain activity.

To test this, the researchers utilized a 7 Tesla MRI scanner. This device is much more powerful than the standard scanners found in most hospitals. The high magnetic field allows for extremely detailed imaging of deep brain structures. It can detect subtle changes in blood flow that weaker scanners might miss.

The study involved nearly eighty participants. These included thirty-two individuals with ME/CFS and nineteen with Long COVID. A group of twenty-seven healthy volunteers served as a control group for comparison.

While inside the scanner, participants performed a cognitive challenge known as the Stroop task. This is a classic psychological test that requires focus and impulse control. Users must identify the color of a word’s ink while ignoring the actual word written. For example, the word “RED” might appear on the screen written in blue ink. The participant must select “blue” despite their brain automatically reading the word “red.”

“The task, called a Stroop task, was displayed to the participants on a screen during the scan, and required participants to ignore conflicting information and focus on the correct response, which places high demands on the brain’s executive function and inhibitory control,” Ms. Inderyas said.

The researchers structured the test to induce mental exhaustion. Participants performed the task in two separate sessions. The first session was designed to build up cognitive fatigue. The second session took place ninety seconds later, after fatigue had fully set in. This “Pre” and “Post” design allowed the scientists to see how the brain adapts to sustained mental effort.

The primary measurement used in this study was functional connectivity. This concept refers to how well different regions of the brain synchronize their activity. When two brain areas activate at the same time, it implies they are communicating or working together.

The results revealed clear differences between the healthy volunteers and the patient groups. In healthy participants, the brain responded to the fatigue of the second session by increasing its connectivity. Connections between deep brain regions and the cerebellum became stronger. This suggests that a healthy brain actively recruits more resources to maintain performance when it gets tired. It becomes more efficient and integrated under pressure.

The pattern was markedly different for patients with Long COVID. They displayed reduced connectivity between the nucleus accumbens and the cerebellum. The nucleus accumbens is a central part of the brain’s reward and motivation system. A lack of connection here might explain the sense of apathy or lack of mental drive patients often report.

Long COVID patients also showed an unusual increase in connectivity between the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. The researchers interpret this as a potential compensatory mechanism. The brain may be trying to bypass damaged networks to keep functioning. It is attempting to use memory centers to help with executive decision-making.

Patients with ME/CFS showed their own distinct patterns of dysfunction. They exhibited increased connectivity between specific areas of the brainstem, such as the cuneiform nucleus and the medulla. These regions are responsible for controlling automatic body functions. This finding aligns with the autonomic nervous system issues frequently seen in ME/CFS patients.

The researchers also looked at how these brain patterns related to the patients’ medical history. In the ME/CFS group, the length of their illness correlated with specific connectivity changes. As the duration of the illness increased, communication between the hippocampus and cerebellum appeared to weaken. This suggests a progressive change in brain function over time.

Direct comparisons between the groups highlighted the extent of the impairment. When compared to the healthy controls, both patient groups showed signs of neural disorganization. The healthy brain creates a “tight” network to handle stress. The patient brains appeared unable to form these robust connections.

Instead of tightening up, the networks in sick patients became looser or dysregulated. This failure to adapt dynamically likely contributes to the cognitive dysfunction known as brain fog. The brain cannot summon the necessary energy or coordination to process information efficiently.

“The scans show changes in the brain regions which may contribute to cognitive difficulties such as memory problems, difficulty concentrating, and slower thinking,” Ms. Inderyas said. This provides biological validation for symptoms that are often dismissed as psychological.

The study does have some limitations that must be considered. The number of participants in each group was relatively small. This is common in studies using such advanced and expensive imaging technology. However, it means the results should be replicated in larger groups to ensure accuracy.

The researchers also noted that they lacked complete medical histories regarding prior COVID-19 infections for the ME/CFS group. It is possible that some ME/CFS patients had undiagnosed COVID-19 in the past. This could potentially blur the lines between the two conditions.

Future studies will need to follow patients over a longer period. Longitudinal research would help determine if these brain changes evolve or improve over time. It would also help clarify if these connectivity issues are a cause of the illness or a result of it.

Despite these caveats, the use of 7 Tesla fMRI offers a promising new direction for research. It has revealed abnormalities that standard imaging could not detect. These findings could eventually lead to new diagnostic tools. Identifying specific broken circuits may also help researchers target treatments more effectively.

The study, “Distinct functional connectivity patterns in myalgic encephalomyelitis and long COVID patients during cognitive fatigue: a 7 Tesla task-fMRI study,” was authored by Maira Inderyas, Kiran Thapaliya, Sonya Marshall-Gradisnik & Leighton Barnden.