A high-salt diet triggers inflammation and memory loss by altering the microbiome

Recent research indicates that consuming high levels of dietary salt for an extended period may disrupt the delicate balance of bacteria in the gut. This disruption appears to trigger a chain reaction that alters gene expression in the brain and leads to cognitive decline. The findings were published in the European Journal of Pharmacology.

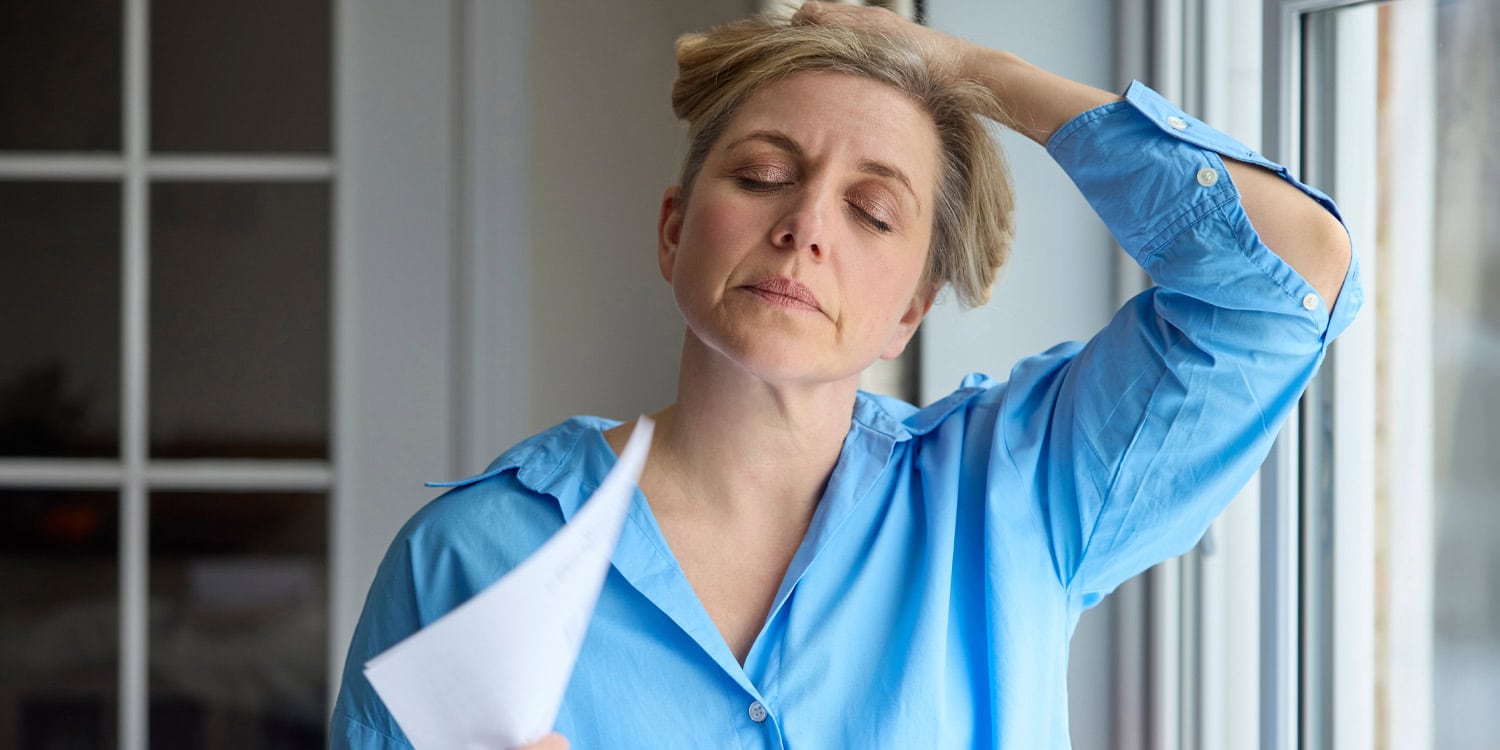

Salt is a fundamental component of the human diet. It is necessary for various physiological functions. However, excessive consumption poses severe health risks. The World Health Organization recommends a daily intake of less than five grams. Despite this guideline, the average adult consumes approximately double that amount. In some nations, the average is even higher. Medical professionals have established that this excess sodium is a primary driver of high blood pressure.

Newer evidence suggests that the damage extends beyond the cardiovascular system to the brain itself. Previous observations showed that high-salt diets could impair memory and emotional regulation. Yet, the biological pathways connecting the stomach to the brain remained partially obscured.

Wenting Xu and colleagues at the Xi’an Jiaotong University Health Science Center in China aimed to map this route. They focused their investigation on the gut-brain axis. This term refers to the biochemical signaling that takes place between the gastrointestinal tract and the central nervous system.

The gut microbiome plays a vital role in this communication network. The trillions of microorganisms living in the digestive system help regulate metabolism and immune responses. A healthy, diverse microbiome supports mental flexibility and memory. The researchers hypothesized that chronic salt intake changes this microbial community. They suspected these changes might induce inflammation in the brain.

To test this hypothesis, the research team designed a controlled experiment using male mice. They selected animals that were six months old. The mice were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The control group received a standard diet containing 0.4 percent sodium chloride. The experimental group was fed a diet with 8 percent sodium chloride. This concentration is considered a high-salt diet. The animals remained on these respective regimens for 180 days. This six-month duration allowed the scientists to observe the effects of chronic exposure.

Throughout the study, the team monitored the physical health of the animals. They measured body weight and water consumption regularly. They also tracked blood pressure using a non-invasive cuff on the tails of the mice. As expected, the mice on the salty diet drank considerably more water. Their systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings increased substantially compared to the control group. These physical changes confirmed that the diet was having a systemic effect on the animals’ physiology.

After six months, the researchers subjected the mice to a battery of behavioral tests. These assessments were designed to measure anxiety and cognitive function. One such assessment was the open field test. Mice were placed in a large, open arena. The researchers recorded how much the animals explored the center versus the edges. The mice fed the high-salt diet spent less time in the center. They preferred the safety of the perimeter. This behavior is interpreted as a sign of heightened anxiety.

Another assessment involved the marble burying test. In this experiment, marbles were placed on top of the cage bedding. Anxious mice tend to bury objects compulsively. The high-salt group buried more marbles than the control group. This reinforced the finding that the diet increased anxiety-like behaviors. The researchers also tested memory using the novel object recognition test. Mice typically spend more time investigating a new object than a familiar one. The mice on the high-salt diet failed to show this preference. This failure indicates a deficit in recognition memory.

Following the behavioral phase, the team examined the brains of the mice. They focused on the hippocampus. This brain region is essential for learning and memory formation. The researchers used specific staining techniques to visualize the neurons. They found a marked reduction in neuronal density in the CA1 and CA3 subregions of the hippocampus. The high-salt diet had caused physically observable damage to the brain tissue. This loss of neurons provides a structural explanation for the memory problems observed in the behavioral tests.

The scientists then analyzed the genetic activity within the hippocampus. They extracted RNA from the brain tissue to see which genes were being expressed. They identified substantial differences between the two groups.

In the high-salt group, genes associated with inflammation were much more active. For example, the gene Il1b showed increased expression. This gene is known to promote inflammatory responses. Conversely, genes that usually help cells survive were less active. The downregulation of the gene Casp4 was particularly notable. This shift in gene expression suggests a heightened state of neuroinflammation.

Simultaneously, the researchers profiled the gut microbiome. They sequenced genetic material from the bacteria found in the mice’s cecum. This analysis revealed that the high-salt diet altered the diversity of the gut bacteria. The composition of the microbial community changed drastically. The abundance of a bacterial phylum called Actinobacteriota increased. Another family of bacteria, Prevotellaceae, decreased. At the genus level, the researchers noted a rise in bacteria such as Dubosiella and Anaeroplasma. These shifts indicated a state of dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance.

The final step was to connect these two datasets. The researchers used statistical methods to look for correlations between the gut bacteria and the brain genes. They found strong associations. The presence of specific gut bacteria mirrored the activity of specific hippocampal genes. For instance, the increase in Dubosiella in the gut was positively correlated with the rise of the inflammatory gene Il1b in the brain. The decline in beneficial bacteria correlated with the suppression of protective genes.

These correlations suggest a potential mechanism. The high-salt diet remodels the gut microbiome. This imbalance likely produces metabolites or signals that travel to the brain. Once there, these signals alter gene expression in the hippocampus. This genetic reprogramming fosters an inflammatory environment. Over time, this inflammation leads to the death of neurons. The loss of these brain cells manifests as the anxiety and memory deficits observed in the mice.

The study offers a detailed look at how diet influences the brain, but there are caveats. The research was conducted on mice. Biological processes in rodents do not always replicate perfectly in humans. Additionally, the study establishes a correlation but does not strictly prove causation. While the statistical links are strong, further work is required to confirm that the bacteria directly cause the gene changes. The current study did not yield results that were not statistically significant, but the sample size was relatively small.

The researchers plan to address these limitations in future work. They intend to perform fecal transplants. This would involve transferring gut bacteria from high-salt mice to normal mice to see if the symptoms transfer. They also plan to investigate these effects in female mice, as this study only used males. They hope to examine other brain regions beyond the hippocampus as well. Confirming these pathways could eventually lead to new strategies for protecting cognitive health through dietary or microbial interventions.

The study, “Chronic high-salt diet induces cognitive impairment and anxiety through gut microbiota alterations,” was authored by Wenting Xu, Chenglin Zhang, Yudan Bai, Hanyue Zhang, Yuyang Wei, Qian Ge, Yuyan Guo, Mai Li, Chanyuan An, Xinlin Chen, and Kaige Ma.