Physical distance shapes moral choices in sacrificial dilemmas

When people feel physically closer to someone who could be harmed, they are less willing to sacrifice that person for the greater good, according to a new finding reported in Cognition & Emotion.

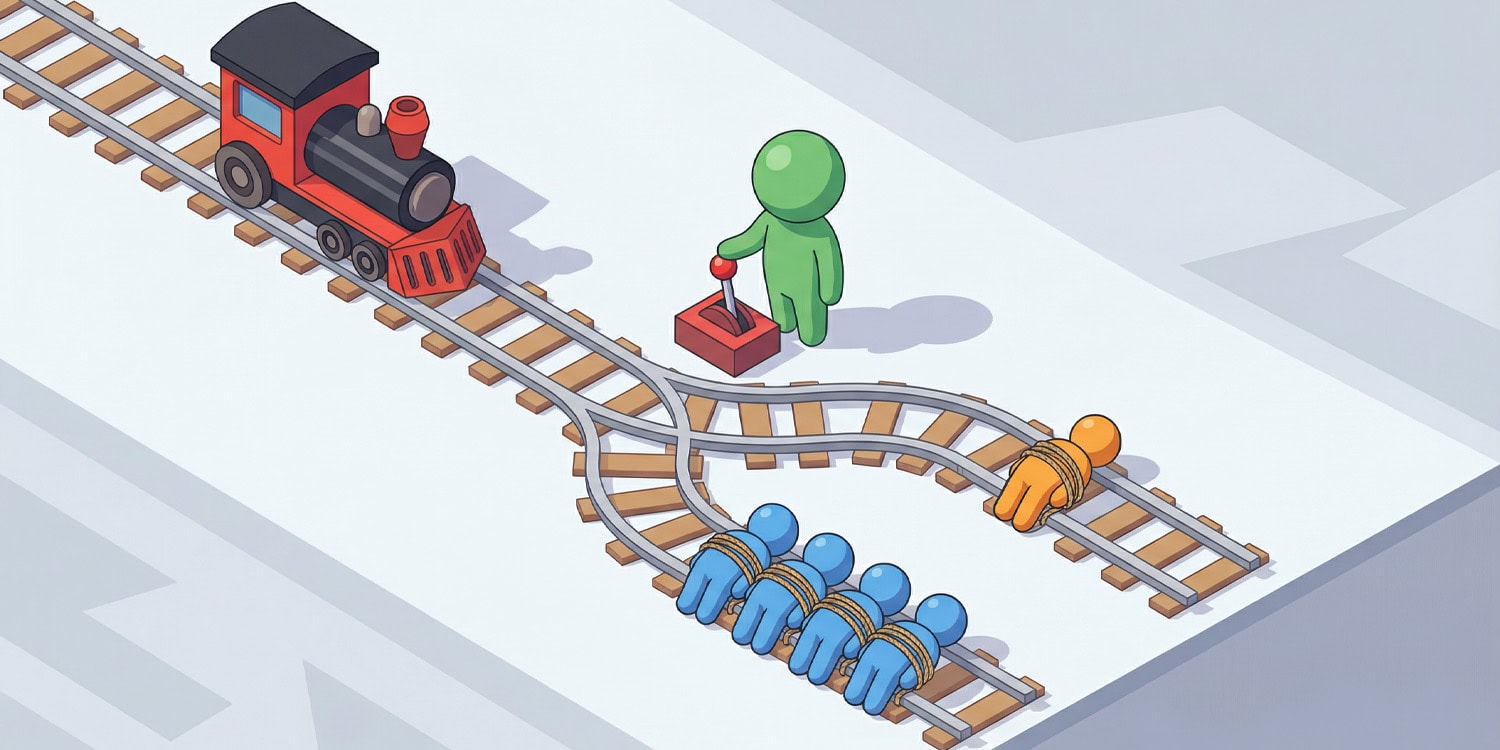

Moral dilemmas, situations where any available option violates an important moral value, have been used to study how people balance rules like “do not harm” against outcomes like saving more lives. Classic examples such as the trolley and footbridge dilemmas show that people often reject utilitarian solutions when harm requires direct physical contact, suggesting that emotional responses play an important role in moral judgment.

The trolley dilemma is a thought experiment that asks whether it is morally permissible to pull a lever to divert a runaway train, sacrificing one person on a side track to save five people on the main line. The footbridge dilemma modifies this scenario by asking if one would physically push a large person off a bridge to stop the train, rather than using a mechanical switch.

Federica Alfeo and colleagues were motivated by an open question in this literature: is it the type of action (e.g., pushing versus pulling a lever), or the physical closeness to the victim, that drives these moral choices? Building on theories of psychological distance and prior work on emotion in decision-making, the authors set out to disentangle how proximity itself shapes moral judgments and emotional reactions.

The researchers conducted two studies using computer-based, interactive moral dilemmas modeled on the footbridge scenario. The scenarios were presented from a first-person perspective, allowing participants to experience the unfolding situation as if they themselves were at the scene.

In Study 1, 261 participants responded to scenarios that required different actions implying different levels of physical proximity to a victim: pushing someone directly, using a gun, or pulling a lever that opened a trapdoor. Participants made a forced choice between a deontological option (letting five people die) and a utilitarian option (sacrificing one person), while their response times were recorded.

After each scenario, participants estimated how physically close they felt to the victim using a visual distance scale. They also rated their emotional responses using standardized ratings, spanning negative emotions (e.g., fear, anger, sadness), moral emotions (e.g., guilt, shame, regret), and positive or neutral emotions. Importantly, emotions were assessed both for the option participants chose (factual emotions) and for the option they rejected (counterfactual emotions).

In Study 2, the researchers tested 46 additional participants to further isolate proximity. Here, the action remained constant across all scenarios (pulling a lever), while only the visual distance to the victim was manipulated. This design allowed the authors to examine whether perceived proximity alone, without changing the action, was sufficient to alter moral choices and emotional reactions.

Across both studies, participants reliably perceived the intended differences in physical distance, confirming that the proximity manipulations worked as designed. In Study 1, moral choices varied systematically with proximity. Participants were less willing to endorse the utilitarian option when the scenario required closer physical contact with the potential victim.

When harm felt more immediate and personal, participants tended to favor deontological choices, even when those choices resulted in worse overall outcomes. Scenarios implying greater distance, by contrast, were associated with a higher likelihood of sacrificing one person to save five.

Emotional responses mirrored these decision patterns. Negative emotions and moral emotions, including guilt, shame, regret, and disappointment, were strongest in high-proximity scenarios and weakest when the victim was farther away. Importantly, emotions associated with the unchosen alternative were consistently more intense than emotions linked to the chosen action.

This pattern suggests that participants anticipated the emotional consequences of both options and tended to choose the one expected to minimize emotional distress. Response times did not meaningfully differ across proximity levels, indicating that emotional intensity rather than deliberation time distinguished the scenarios.

Study 2 replicated and clarified these effects while holding the action constant. Even when participants always performed the same action, greater perceived distance increased utilitarian responding, whereas closer proximity reduced it. Emotional patterns showed a similar structure, with proximity amplifying negative and moral emotions and counterfactual emotions again exceeding factual ones.

Together, these findings show that physical closeness itself, not just the type of action, plays a central role in moral decision-making.

These findings are based on hypothetical, computer-based dilemmas, which may not fully capture how people behave in real-world moral situations involving genuine stakes and consequences.

The research, “The closer you are, the more it hurts: the impact of proximity on moral decision-making,” was authored by Federica Alfeo, Antonietta Curci, and Tiziana Lanciano.