So you think you can build an NCAA bracket? Behind the scenes of the arduous March Madness process

Feb. 11, 2026 An Indianapolis hotel

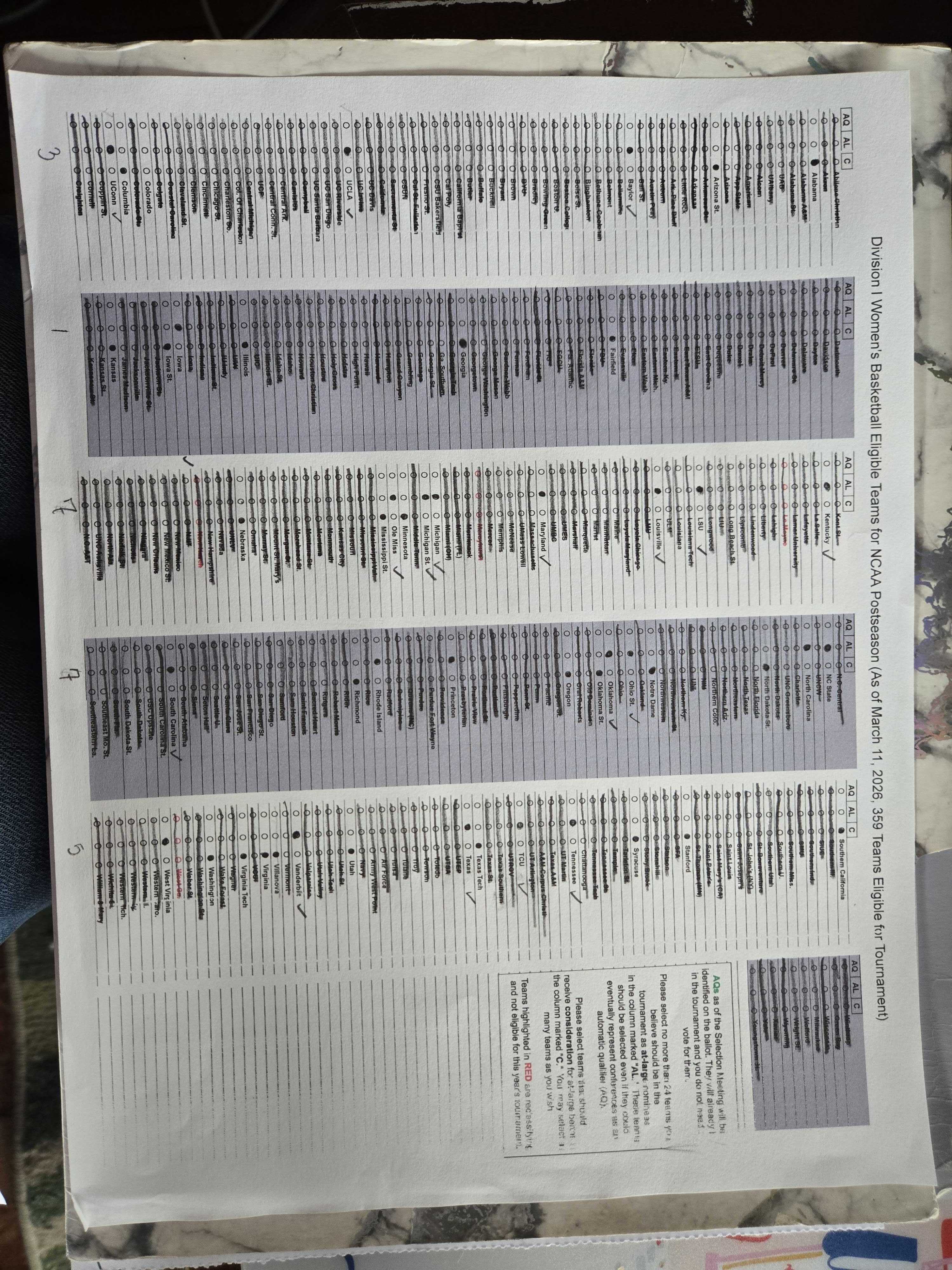

I’m staring at a collection of 1,095 circles organized by threes into tidy columns, visions of scantrons past dancing in my head. The fact that no one holds a master answer key does nothing to quell the stress of getting it right.

It’s edging late into the night in Indianapolis ahead of the NCAA women’s basketball selection committee’s mock selection exercise at the national office, and I’m agonizing over this page. My task is to rank the 30-plus at-large teams I shaded for selection to or consideration for the NCAA tournament field. Washington above Notre Dame? Where do Princeton or Georgia fit? Is Syracuse No. 35 or a first-four out?

At a breaking point, I begin scribbling school names onto a piece of stationery with alternating colored lines. There are too many variables to consider. Too few hairs to split between. By the time I reach “28,” I’m judging selections loosely on NET rankings with a pinch of any random criteria fitting the bill. I feel like the human embodiment of the shrug emoji as I try to rationalize each decision; I mentally force the flexed-biceps emoji instead.

Do I think I can build an NCAA bracket? Of course. Don’t we all?

Feb. 12, 2026 1:15 p.m. ET NCAA headquarters

A selection of reporters, broadcasters, conference personnel and NCAA leadership walk into a boardroom. The tables are arranged like a rectangular 2000s computer lab, the March Madness laptops and mice splayed in front of flat screens lowered in the middle of the room, facing the attendees.

Those of us on the board-for-a-day go around and make introductions. If this were the real committee meeting, there would be no need. The time-intensive process of selecting, seeding and bracketing teams into the tournament field begins months prior to March.

Each of the 12-person committee serves a five-year term and is assigned to monitor a primary conference and a secondary one. There are weekly and monthly check-ins that might include information like the impact of last month’s winter storm on teams and scheduling. Did a key player miss time? Was there a conference-defining victory recently? Who is in contention for an at-large bid?

They give reports at each of these committee meetings throughout the season, as well as reports from head coaches within regional advisory committees. They discuss game results, metrics, matchups to watch and rewatch. Their true work occurs during the long days from the Wednesday before Selection Sunday until hours before the reveal.

Every bit of information a committee member receives needs to be shared with the group for optimal results. Everything is based on integrity in the three-prong process. Selection is the body of work. Seeding is the “who are they right now?” Bracketing is … well, that comes later.

All conferences are discussed. All relevant conversations stay in the room. And historical benchmarks mean nothing.

2:15 p.m.

There are no March Madness-branded “I voted” stickers at the NCAA headquarters. If there were, they would run out fast. Unbeknownst to us newbies who agonized over the exact line seeding of our teams the night prior, our exact listing is irrelevant. It’s time to vote and vote and vote again as we whittle down a large group into chunks of entries.

First, we each privately input into the software the names of up to 24 teams we believe should be at-large selections, plus an unlimited number of those under consideration. Teams are moved onto the at-large nomination board based on how many votes they received in each category. Our vote moved 22 onto the board.

We then continue to evaluate using the committee's "list eight, rank eight, move four" process. We vote in our top eight selections from the board, resulting in a collective eight that move into a new board. We rank those eight individually, leading into four that will move into the field. We keep going in that manner, until it’s close to the end when cuts are near. The committee can then vote in two and even one sole team at a time.

This is the process of selecting and later seeding a field. It’s arduous and intentional, a fail-safe to properly fit in each worthy team in a way that befits their résumé.

It’s also very confusing, even to those of us in the room digitally clicking the bubbles of our choices, which is why the NCAA outlined, for transparency, the exact procedural steps. Because as much as the basketball of March Madness is a national pastime, so, too, is analyzing the committee’s work building a bracket. At least one fan base is bound to be mad, lobbing allegations of bias or purposefully helping/hurting their team.

Dawn Staley felt her South Carolina Gamecocks were snubbed from the No. 1 overall seed last year. UConn fans were outraged about being placed on the West Coast, while for much of the previous decade, those outside Storrs were upset at the team’s prime regional location being a couple hours max from campus. There is a high chance this year that TCU, as a double-digit seed, doesn’t leave its own bed until the Final Four.

None of that context is on the selection committee’s minds through this process. And if someone, for example, mentions as we’re seeding the 4-line that we’re voting for the final teams we believe should be hosting first-and-second round games, they’re politely corrected by the chair. It is about the next four best teams on the mini board that should be in the field.

The results should not impact the process itself.

4 p.m.

It’s all made up, and the quads don’t matter. At least, that’s the joke running in my head.

The time is finally here to seed teams, and the mock chair has been waiting to strike up this conversation. It’s UConn, right? Or, for the sake of discussion, could it be UCLA with its 14 Quad 1 wins?

Ah, but hold on. That large-font list of team selection criteria/priorities placed to the left of each computer doesn’t say anything about quadrant victories. NCAA personnel tell us that the four quadrants are an organizational tool for delineating game data into digestible points. Not all of them are built equal. Defeating a team ranked second in NET is different from one ranked 20th, even if they are both Quad 1. Context is ingrained everywhere.

Therefore, it isn’t a reason to seed a team before or after another. And with that, my muscle emoji begins to fade. I’d like to crumple up and shoot my top 30 list into a garbage can for at least one swish on the day.

The chair decides we should go down the list (in alphabetical order) to compare: bad losses, common opponents, competitive in losses, early performance vs late performance, head-to-head, NET ranking, observable component, overall record, regional rankings, significant wins, strength of schedule, Wins Above Bubble (WAB) ranking.

The instructors identify one major data point to which the committee has privileged access. There are five regions for the 32 conferences, and though it sounds odd, the Big Ten and Big East are together in one of those regions. Three times a year, the coaches rank the top 20 teams, and if we were the committee, we could ask the member leading that to tell us the coaches’ thoughts. We would then use it to inform our personal voting decision.

It’s one of the most illuminating pieces of information of the day. The selection committee is often treated as a table of deities pulling levers and bopping buttons to design a bracket of their choosing. That’s not quite true. They are guided by rules and regulations, criteria and principles, and most importantly, they do not make these selections in a vacuum of their own control.

We vote and vote, and end up with UConn, UCLA, South Carolina and Texas as our 1-4 seeds. Are we all good with that?

I’m not. Nor are a few others in the room. We glance at our list of criteria/principles to hit our talking points. Texas and South Carolina split the season series, are similar in NET ranking and each lost to a different SEC power. Texas played the more difficult schedule, had the higher non-conference WAB and defeated UCLA, our No. 2 seed.

If it were the actual committee, the chair could opt to put it to a secret vote: South Carolina or Texas for the No. 3 overall seed? And it’s not a one-shot choice, as real committee members reminded us consistently. Every day leading up to Selection Sunday, the committee could and would reassess any part of their work.

Time to move on. We speed-seed the top 16 teams before dinner. Quite a few tiebreakers come up if two teams acquired the same number of points within a single ballot. LSU and Louisville are tied for the No. 6 seed. Louisville wins. Same for Kentucky and Michigan State at No. 14. This will be a more time-intensive process the week of Selection Sunday.

At the moment, it all seems trivial. By the end, we appreciate the magnitude.

6:30 p.m.

The impact of the Texas-South Carolina conversation lands as sour as the lemon cake at dinner.

The NCAA tech team back-filled a full 68-team field for us so we could view the bracketing process in action. The flatscreens are filled with a spreadsheet separated into four columns, two each for the super-regional sites at Fort Worth and Sacramento. The seed list sits underneath. An NCAA administrator is poised with a list of principles.

A cursor drags UConn to Fort Worth, the closer location of the two earned by the top overall seed. The Huskies will play Friday and Sunday, giving them the advantage of an extra day ahead of the Final Four. UCLA then goes to Sacramento, a move that benefits them, anyway. South Carolina is placed in Fort Worth, and Texas to Sacramento.

The mock committee members begin to stir at the realization that one difference in true seed can impact more than the number. Texas could have been close to home, a pro for them as well as a fan attendance windfall, while South Carolina faced lengthy travel either way. We can’t go back and adjust for that reason alone. We already did the work to fairly rank; now we’re bracketing based on that.

It highlights that every opinion should be voiced, every critical decision put to a vote and that every individual seed deserves an in-depth conversation. It is a reality that carries on through the bracketing as we go seed-line by seed-line, taking into account travel distance from site, mode of transportation and fan accessibility.

The errors compile.

There are too many SEC and Big Ten teams. If the first four teams from one conference are seeded within the top four lines, they must be placed in different regionals. But, we also don’t want conference rematches until the regional final, whenever possible. The accumulation of seed numbers climbs at the bottom of each column as we attempt to keep it balanced. Our mock is a six-point differential. Not bad.

The administrator lifts schools from the S-curve up into something of a criss-crossed zig-zag, daring someone to play connect-the-dots. It’s late, our mock chair accidentally found herself locked outside the floor-to-ceiling glass windows, and our brains are at capacity laughing at the absurdity.

We’ve slammed multiple days of bracketing into a two-hour window, and I’m amazed my own personal seed-by-seed listing was my biggest conundrum 24 hours ago. Now we’re talking length of flights and fan attendance at first-round host sites; fairness and principles; if it’s right, the conference champion of America East might play the same second-round opponent in consecutive seasons. It’s too much for one person.

Each click of a team lights up the bracketing program like the ignition switch to a dying car’s dashboard. Don’t worry, some screens look more purple and others are more blue (denoting errors that violate various principles), we’re told. That doesn’t explain the other three colors glinting off the screens.

The program spells out the problem; it doesn’t solve it. That’s for us to puzzle out. The real committee will often save drafts at major conundrums so it can bracket out multiple versions. No matter which one is chosen, people are bound to be mad.

9:20 p.m. An Indianapolis hotel

Back at the hotel bar, on the phone screen balancing against a stack of menus, Vanderbilt is beating the brakes off Texas. Arguing for the Longhorns as the No. 3 seed is a thing of the past. That same weekend, the real committee will move Texas down to No. 5.

Our mock bracket is already obsolete, less than an hour after we’ve called it a day. A few media members who have done this previously assured everyone before leaving that history says that will be the case. With our committee hats off, we can talk of tournaments past again.

It is one thing to know the criteria and principles the committee follows to build a bracket. It is another entirely to sit in the room and experience a simulation of it. The informational input spreads far wider than 12 people’s thoughts, combined with stats on the screen. The voting system allows better fine-tuning than smushing together everyone’s lists. Processes for everything means no one can bend it to their own will.

My pen will still be ready on Selection Sunday to mark up the bracket and scribble out talking points. Which teams were left on the bubble that shouldn’t have been? Is TCU really in Fort Worth? Did Duke deserve a better seed? But, I’ll also have a deeper appreciation for all the judgment calls that had to be made on a piece of paper that will eventually be ripped up by the masses.

Everyone thinks they can build an NCAA bracket. That doesn’t mean it’s easy.