Recent LSD use linked to lower odds of alcohol use disorder

Recent analysis of federal health data suggests that the recreational use of LSD is associated with a lower likelihood of alcohol use disorder. This finding stands in contrast to the use of other psychedelic substances, which did not show a similar protective link in the past year. The results were published recently in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs.

Alcohol use disorder affects millions of adults and stands as one of the most persistent public health challenges in the United States. The condition involves a pattern of alcohol consumption that leads to clinically detectable distress or impairment. Individuals with this disorder often find themselves unable to control their intake despite knowing it causes physical or social harm. Standard treatments exist, but relapse rates remain high. Consequently, medical researchers are exploring alternative therapeutic avenues.

In recent years, attention has shifted toward the potential utility of psychedelic compounds. Substances such as psilocybin and MDMA have shown promise in controlled clinical trials for treating various psychiatric conditions. However, there is a substantial distinction between administering a drug in a hospital with trained therapists and taking a drug recreationally. James M. Zech, a researcher at Florida State University, sought to investigate this difference. Zech collaborated with Jérémie Richard from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Grant M. Jones from Harvard University.

The team aimed to determine if the therapeutic signals seen in small clinical trials would appear in the general population. They utilized data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. This government project recruits a representative group of American citizens to answer detailed questions about their lifestyle and health. The researchers pooled data collected from 2021 through 2023. The final dataset included responses from 139,524 adults.

To ensure accuracy, the investigators did not simply look at who used drugs and who drank alcohol. They employed statistical models designed to account for confounding factors. They adjusted their calculations for variables such as age, biological sex, income, and education level. They also controlled for the use of other substances, including tobacco and cannabis. This process helped them isolate the specific relationship between psychedelics and alcohol problems.

The researchers assessed whether participants met the diagnostic criteria for alcohol use disorder within the past year. They also looked at the severity of the disorder by counting the number of symptoms reported. These symptoms range from experiencing cravings to neglecting responsibilities due to drinking.

The analysis revealed a distinct association regarding lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD. Adults who reported using LSD in the past year were significantly less likely to meet the criteria for alcohol use disorder. The adjusted odds ratio indicated a 30 percent reduction in likelihood compared to non-users. Among those who did have the disorder, LSD users reported approximately 15 percent fewer symptoms.

The study did not find the same pattern for other popular substances. The researchers analyzed the use of MDMA and ketamine over the same twelve-month period. Neither of these drugs showed a statistical association with the presence or absence of alcohol use disorder. This suggests that the potential protective effect observed with LSD might be specific to that compound or the context in which it is typically used.

A more complex picture emerged when the team examined lifetime usage histories. The survey asked participants if they had ever used certain drugs, even if they had not done so recently. Individuals who had used psilocybin or MDMA at any point in their lives were actually more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol use disorder in the past year. In contrast, lifetime use of DMT was linked to a lower probability of having the disorder.

These contradictory findings highlight the difficulty of interpreting observational data. The researchers propose several theories to explain why lifetime psilocybin use might track with higher alcohol problems while past-year LSD use tracks with lower ones. It is possible that individuals with existing substance use issues are more inclined to experiment with psilocybin.

Another possibility involves the nature of the psychedelic experience itself. While clinical trials optimize the setting to ensure a positive outcome, recreational use carries risks. The authors note that unsupervised trips can sometimes be distressing or psychologically destabilizing. If a person has a negative experience, they might increase their alcohol consumption as a way to cope with the resulting stress.

Conversely, the potential benefits of LSD could stem from psychological shifts often reported by users. Previous studies indicate that psychedelics can alter personality traits. Users often report increased “openness” and decreased “neuroticism” after a profound experience. If LSD facilitates such changes more reliably in naturalistic settings, it could theoretically reduce the psychological drivers of heavy drinking.

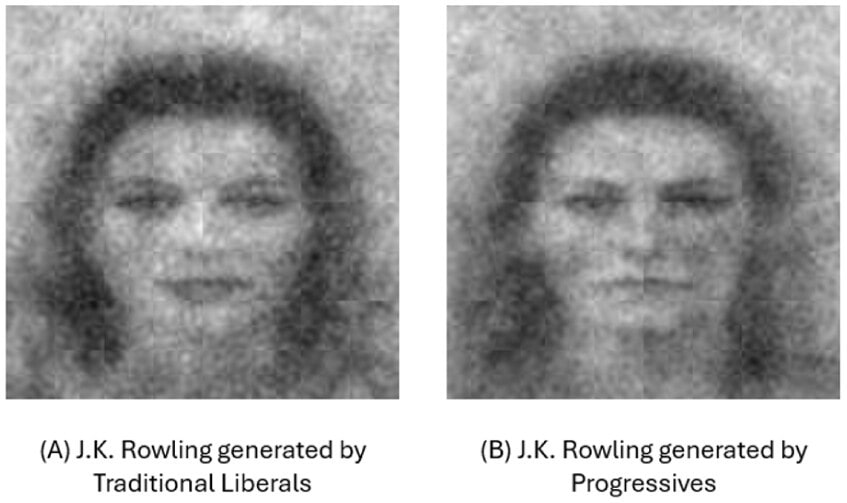

These results contribute to a growing body of literature that often points in different directions. For example, a survey of Canadian adults previously found that people self-reported large reductions in alcohol use after taking psychedelics. In that study, respondents specifically cited psilocybin as the most effective agent for change. The discrepancy between that survey and the current findings underscores the difference between self-perception and objective diagnostic criteria.

Clinical research has also provided evidence for the efficacy of psilocybin, provided it is administered professionally. A small trial conducted in Denmark tested a single high dose of psilocybin on patients with severe alcohol use disorder. In that experiment, patients received psychological support before and after the session. The clinicians observed a reduction in heavy drinking days and cravings.

The contrast between the clinical success of psilocybin and the negative association found in the general population data is noteworthy. It suggests that the element of therapy and professional guidance may be essential for achieving therapeutic outcomes. Without the safety net of a clinical setting, the risks of using these powerful substances may outweigh the benefits for some individuals.

There are some limitations to the current study that affect how the results should be viewed. The analysis is cross-sectional, meaning it captures a snapshot in time rather than following people forward. As a result, the researchers cannot prove that LSD causes a reduction in drinking. It is equally possible that people who choose to use LSD simply have different lifestyle patterns that protect them from alcohol addiction.

The study also faced constraints regarding the data available. The federal survey only asked about past-year use for a subset of drugs. For psilocybin, the survey only asked about lifetime use. This prevented the researchers from seeing if recent psilocybin use might have shown a positive benefit similar to LSD. Additionally, the data relies on self-reporting. Participants may not always be truthful about their involvement with illegal substances or the extent of their alcohol consumption.

The researchers emphasize the need for longitudinal studies in the future. Tracking individuals over many years would clarify the order of events. It would show whether psychedelic use typically precedes a change in drinking behavior. The authors also suggest that future research should measure the dosage and frequency of use. Understanding whether a person took a substance once or heavily and repeatedly is necessary to fully understand the risks and benefits.

The study, “The Relationship Between Psychedelic Use and Alcohol Use Disorder in a Nationally Representative Sample,” was authored by James M. Zech, Jérémie Richard, and Grant M. Jones.

*Stares intently*

*Stares intently*

Lake Manly returns.

Lake Manly returns. A significant clue.

A significant clue.

Long before there were flowers.

Long before there were flowers. Germans have a word for this kind of thing.

Germans have a word for this kind of thing. Tylos is one weird world.

Tylos is one weird world. It's not unprecedented.

It's not unprecedented.  It’s important to get help.

It’s important to get help.

Take note, ChatGPT.

Take note, ChatGPT.

Why was she buried this way?

Why was she buried this way?

We have to rethink this.

We have to rethink this.

A tragic irony.

A tragic irony.

And you can view it now.

And you can view it now. The values that shape our lives.

The values that shape our lives.

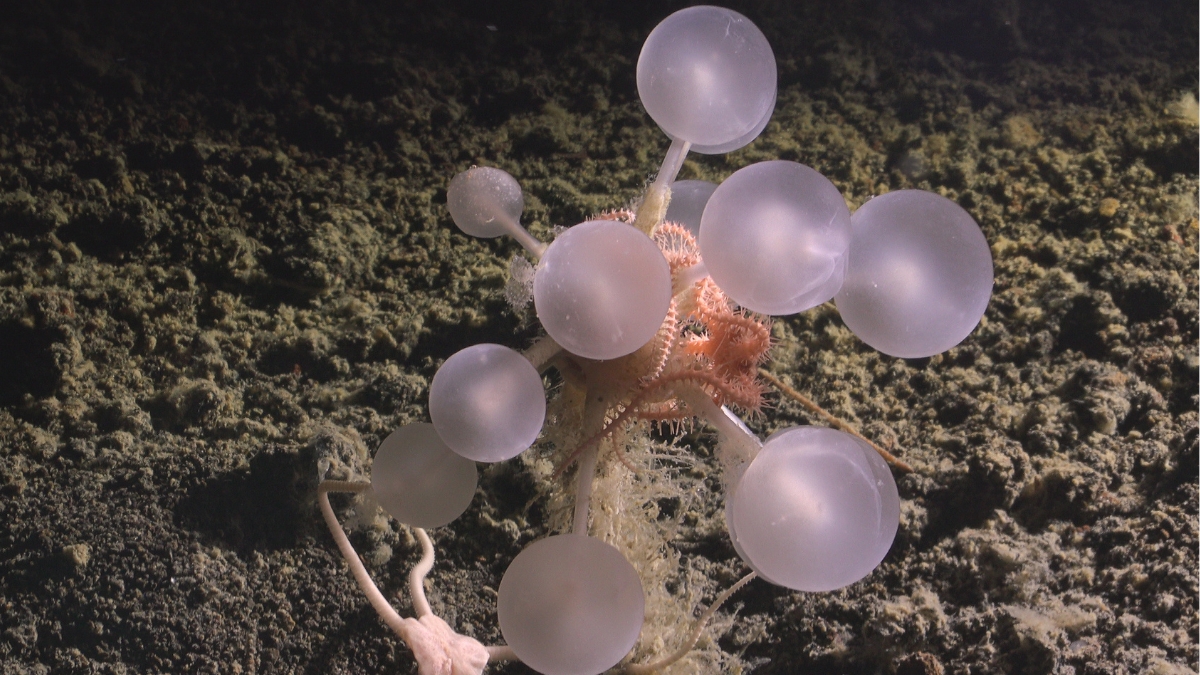

SpongeBall DeathPants.

SpongeBall DeathPants.

Incredible!

Incredible!

Attention hijacked.

Attention hijacked.

The evidence is growing.

The evidence is growing.

Our weekly science news roundup.

Our weekly science news roundup.

A creative sweet spot.

A creative sweet spot.

More than one way to sequence a cat.

More than one way to sequence a cat.

The first time this has ever been seen.

The first time this has ever been seen.

"I obviously wasn't aware of the dangers."

"I obviously wasn't aware of the dangers."

A profile of this mysterious condition is emerging.

A profile of this mysterious condition is emerging.