New psychology research flips the script on happiness and self-control

A new study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science challenges the conventional wisdom regarding the relationship between self-discipline and happiness. The findings suggest that psychological well-being acts as a precursor to self-control rather than a result of it. This research indicates that individuals who prioritize their emotional health may be better equipped to pursue long-term goals than those who rely solely on willpower.

Psychology has traditionally viewed self-control as a prized human capacity that is essential for a successful life. The general assumption holds that the ability to resist short-term temptations in favor of long-term goals leads to better health, career success, and financial security. By extension, scholars and the public alike often assume that exercising high self-control leads to increased happiness and life satisfaction.

Despite the popularity of this belief, the scientific evidence supporting a direct causal link from self-control to well-being has been inconclusive. Many previous studies relied on correlational data, which can show that two things are related but cannot determine which one causes the other. Other studies that attempted to track these variables over time faced methodological issues that made it difficult to draw firm conclusions about directionality.

“Our work was driven by a significant gap in the existing research. For years, psychologists have operated under the strong assumption that self-control is a key driver of well-being,” said study author Lile Jia, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore and director of the Situated Goal Pursuit (SPUR) Lab.

“The narrative is that if you are more disciplined, you will be happier and more satisfied with life. However, when we examined the scientific literature, the causal evidence for this claim was surprisingly weak and fraught with issues. Most studies were correlational, and the few longitudinal studies attempting to establish causality had methodological limitations that made their conclusions ambiguous.”

“At the same time, there are strong theoretical reasons to suspect the causal arrow might point in the opposite direction,” Jia explained. “For example, Barbara Fredrickson’s ‘broaden-and-build’ theory suggests that positive emotions—a core component of well-being—broaden our mindset and help us build personal resources. We reasoned that these resources could, in turn, facilitate better self-control.”

“So, the central motivation was to rigorously test these competing causal pathways. We wanted to clarify the directionality of this important relationship between self-control and well-being using more robust statistical methods (the RI-CLPM) and a three-wave longitudinal design, which is better suited for making causal inferences than the two-wave designs used in prior work.”

The researchers conducted two separate longitudinal studies. Study 1 involved 377 working adults recruited from an Asian country. The participants were part of a larger project regarding career development and lifelong learning.

The researchers collected data from these participants at three distinct time points, with each wave separated by a six-month interval. This design allowed the team to track changes within the same individuals over a period of one year. To measure self-control, the participants completed a 20-item scale that assessed their ability to inhibit impulses, initiate work, and continue good behaviors.

For the assessment of well-being, the participants responded to a scale designed to be culturally appropriate for the population. This measure included items asking about their levels of happiness, self-worth, and appreciation for life. The team also utilized a statistical technique known as the random intercept cross-lagged panel model.

This specific analytical approach is significant because it separates stable personality traits from temporary fluctuations within a person. It allowed the researchers to determine if a specific increase in well-being at one time point predicted a subsequent increase in self-control at the next time point. By isolating these within-person changes, the model provides a stronger test for potential causal influence than traditional methods.

The results from the first study revealed a pattern that contradicted the traditional narrative. Earlier levels of self-control did not reliably predict improvements in well-being six months later. Simply exercising discipline did not appear to make participants happier in the future.

In contrast, the data supported the reverse hypothesis. Participants who reported higher levels of well-being at one time point exhibited greater self-control at the next measurement wave. Feeling well appeared to function as a precursor to functioning well.

To ensure these findings were not specific to one culture or time interval, the researchers conducted a second study. Study 2 recruited a larger sample of 1,299 working adults in the United States. This study followed a similar three-wave design but utilized a shorter time frame to capture more immediate effects.

Participants in the American sample completed surveys once a month for three consecutive months. They answered the same self-control questions used in the first study. To measure well-being, they completed a scale assessing positive feelings, optimism, and vitality.

The analysis of the American data yielded results that mirrored those of the Asian sample. High levels of self-control at the start of a month did not lead to increased well-being the following month. The anticipated reward of happiness following disciplined behavior did not materialize in the short term.

However, the reverse relationship remained significant and positive. Individuals who felt more optimistic and energetic at the beginning of the month demonstrated better self-control a month later. This replication across two different cultures and timeframes provides robust evidence that the primary direction of influence flows from well-being to self-control.

“The most surprising result was the consistent lack of evidence for the popular belief that self-control predicts later well-being,” Jia told PsyPost. “Given how deeply this idea is embedded in both scientific thinking and popular culture, we expected to see at least a small effect in that direction. To find that the data from two separate studies so clearly supported only the path from well-being to self-control was quite striking. It really challenges a foundational assumption and underscores the need to re-evaluate how we think about these two critical aspects of a good life.”

The researchers conducted supplementary analyses to further check these patterns. In the first study, participants also provided daily reports of their mood and behavior for a week. These daily records showed that while positive emotions predicted self-control months later, self-control did not uniquely predict daily positive emotions when general well-being was taken into account.

The researchers propose that positive emotions may help replenish the mental energy required to resist temptations and stick to difficult tasks. When people feel good, they may be more open to challenges and better at managing conflicting goals. This aligns with the idea that well-being acts as fuel for the engine of self-control.

“The most important takeaway for the average person is to reconsider how they approach self-improvement,” Jia said. “The common advice is often to ‘just try harder’ or to focus on building discipline through sheer willpower. Our findings suggest a potentially more effective, and certainly more pleasant, alternative: prioritize your well-being to build your self-control.”

“Instead of viewing happiness as a reward you get after achieving your goals through discipline, think of well-being as the fuel that powers the engine of self-control. If you want to get better at resisting temptations, starting new projects, or sticking with good habits, a great first step is to invest in activities that make you feel happy, energetic, optimistic, and appreciative of life. Our research indicates that feeling well precedes functioning well.”

The study’s strength lies in its use of a three-wave longitudinal design across two diverse cultural samples. But as with all research, there are some limitations. The statistical framework used relies on the assumption that the relationships between variables remain constant over time. It is also possible that unmeasured third variables, such as changes in sleep, stress, or social support, could influence both well-being and self-control simultaneously.

It is also important to note that the absence of a short-term effect does not mean self-control has no relationship with happiness. “A crucial caveat is that ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence,'” Jia explained. “Our study failed to find a within-person causal effect of self-control on well-being, but this does not mean that self-control is unimportant for happiness altogether.

“It’s possible that having high self-control as a stable, long-term trait contributes to a person’s overall life satisfaction (a between-persons effect), even if short-term fluctuations in self-control don’t cause short-term fluctuations in well-being.”

“So, the misinterpretation to avoid is thinking ‘self-control doesn’t matter for happiness.’ A more accurate interpretation is that if you are looking for a positive change, our evidence suggests that boosting your well-being is a more direct and effective way to improve your self-control, rather than the other way around.”

Future research could explore the specific mechanisms that allow well-being to improve self-control. It may be that positive moods accelerate habit formation or enhance cognitive flexibility. Understanding these processes could lead to better interventions for people struggling with self-regulation.

“The path to greater self-control doesn’t have to be a grim, effortful struggle,” Jia added. “Instead, it can be paved with positive experiences. By actively cultivating joy, engagement, and meaning in our lives, we are not just making ourselves feel better in the moment; we are also building the psychological resources we need to be more effective and successful in the future. It places the pursuit of well-being at the very center of personal growth.”

The study, “Feeling Well, Functioning Well: How Psychological Well-Being Predicts Later Self-Control, but Not the Other Way Around,” was authored by Shuna Shiann Khoo, Lile Jia, Ismaharif Ismail, Ying Li, Liangyu Xing, and Jolynn Pek.

Here it comes!

Here it comes!

Is there a better approach?

Is there a better approach? Decades of assumptions could be wrong.

Decades of assumptions could be wrong. That's not even a worst-case scenario.

That's not even a worst-case scenario.

It's not just a hallucinogen.

It's not just a hallucinogen.

*Stares intently*

*Stares intently*

Lake Manly returns.

Lake Manly returns. A significant clue.

A significant clue.

Long before there were flowers.

Long before there were flowers. Germans have a word for this kind of thing.

Germans have a word for this kind of thing. Tylos is one weird world.

Tylos is one weird world. It's not unprecedented.

It's not unprecedented.  It’s important to get help.

It’s important to get help.

Take note, ChatGPT.

Take note, ChatGPT.

Why was she buried this way?

Why was she buried this way?

We have to rethink this.

We have to rethink this.

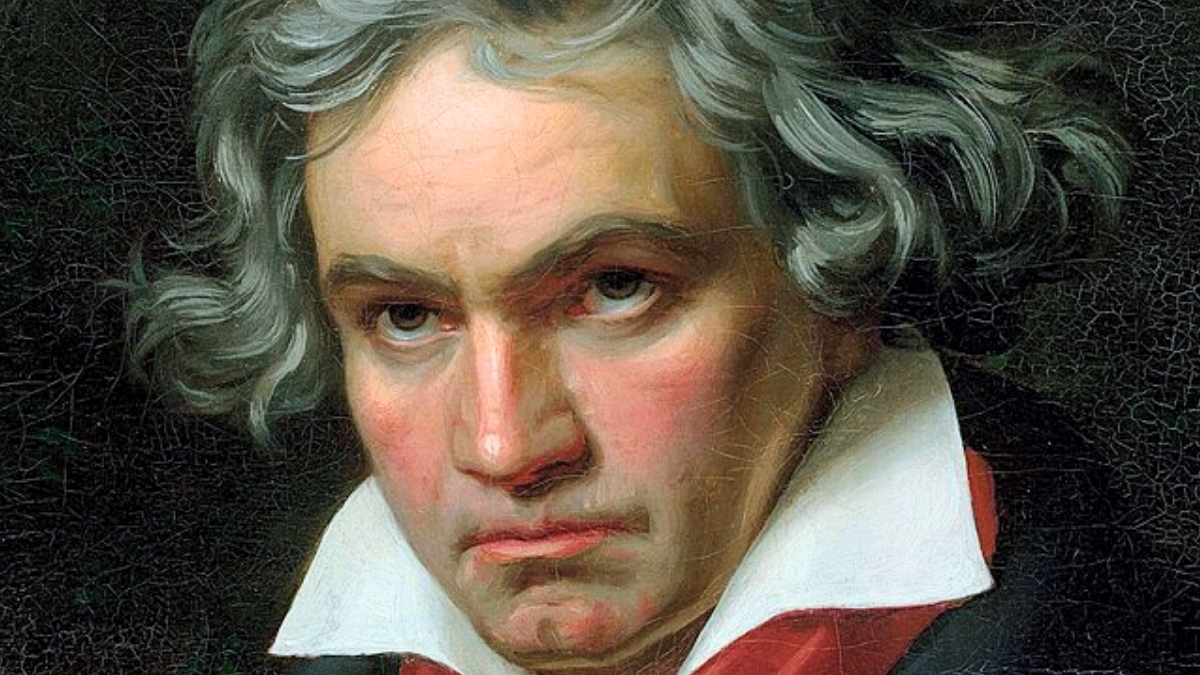

A tragic irony.

A tragic irony.

And you can view it now.

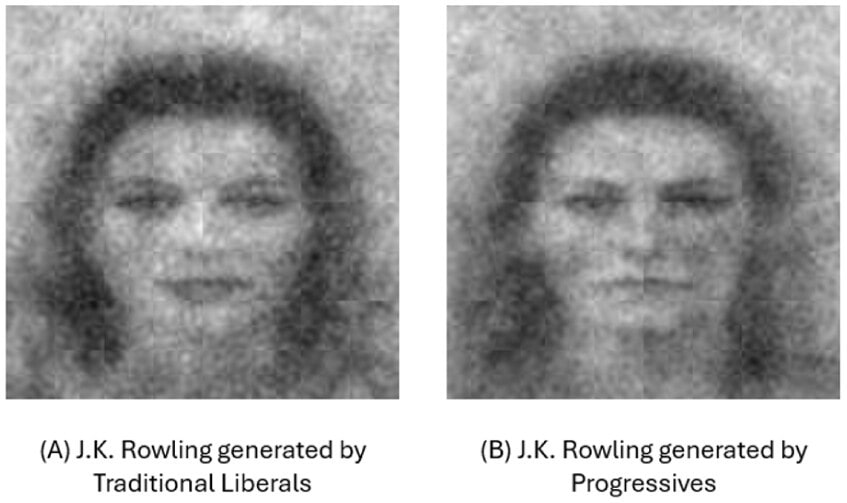

And you can view it now. The values that shape our lives.

The values that shape our lives.

SpongeBall DeathPants.

SpongeBall DeathPants.

Incredible!

Incredible!

Attention hijacked.

Attention hijacked.

The evidence is growing.

The evidence is growing.

Our weekly science news roundup.

Our weekly science news roundup.

A creative sweet spot.

A creative sweet spot.

More than one way to sequence a cat.

More than one way to sequence a cat.

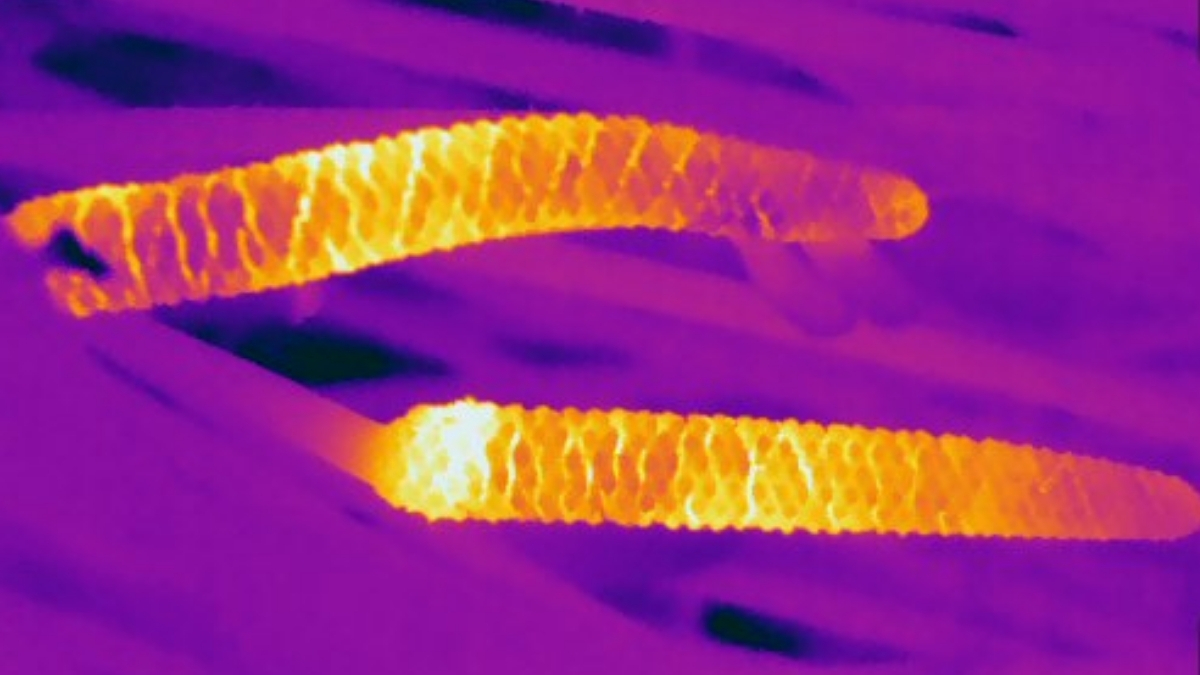

The first time this has ever been seen.

The first time this has ever been seen.

"I obviously wasn't aware of the dangers."

"I obviously wasn't aware of the dangers."

A profile of this mysterious condition is emerging.

A profile of this mysterious condition is emerging.