Rare 2-Million-Year-Old Infant Facial Fossils Expand What We Know About Prehistoric Human Children

The prototype system can generate enough electricity for almost 1,900 miles of annual driving and aims to cut reliance on the grid.

© Nissan

A closer look at Nissan’s solar power generation system

© Nissan

The 20-year-old Texan will serve as reserve driver through 2026 after impressing in Formula 2 and free-practice sessions.

© Alex Slitz

New four-banger makes 324 hp, carryover PHEV 4xe maintains 375 hp.

© Stellantis

Jeep simplifies the Grand Cherokee lineup with four-cylinder and PHEV powertrains.

© Stellantis

Kardashian suffered a ‘little aneurysm’ reportedly due to stress

© Good Morning America

Police said a 22-year-old man was arrested at the scene on suspicion of murder and attempted murder

© PA Wire

State Attorney General Ken Paxton parroted claims by the Health Secretary which have been strongly refuted by medical professionals

© AP

‘I’ve never heard anything like that before,’ said air traffic control

© Getty Images

While the government does not keep a record of the number of British nationals overseas, around 5,000 British nationals are thought to be on the island

© AP

Age is a significant factor to why you might be struggling with the cold this winter

© Alamy/PA

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Zachary Porthen will make his international bow at Wembley with Kolbe deployed at full-back

© Getty Images

Donald Trump appeared to wander off while being given a tour by new Japanese prime minister Sanae Takaichi.

© AP

A total of 9,462,185 Penalty Charge Notices were given out last year, new data from London Councils has revealed

© PA

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Sean Bean has revealed that Daniel Day-Lewis invited him over to spend time at his house before they began filming Anemone.

© ITV

I spent weeks testing a range of heated clothes airers in a real household setting

© Zoe Griffin/The Independent

From incredible storylines and expansive worlds to family-friendly fun, I share my pick of the best PS5 games

© PlayStation Studios, Larian Studios, Kojima Productions & CD Projekt Red

© PA Archive

Experts at Naples' Tesoro di San Gennaro use technology to keep gems secure

© Reuters

Monday’s incident at PPG Paints Arena marks the third fall at a major Pittsburgh sports venue this year

© Getty

We put a range of brollies to the test in drizzle, heavy rain and wind over several weeks

© The Independent

© Getty Images

© Department of Defense

Court records show that at least two of the men are employees of the restaurant Yucatan

© Google Maps/ABC13

Scottish musician accused Shakira of ‘stripping off’ for attention in her 2010 music video

© Getty Images

I whipped up all manner of meals to bring you my pick of the top-performing pans

© Alicia Miller/The Independent

© Jordan Reynolds/PA

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Three roads will remain closed until 2026

© Steve Parsons/PA

Millions of Americans have to fight feelings of lethargy and sadness that come with the colder seasons

© Getty Images/iStock

© PA Wire

Kelce is the fourth tight end in NFL history to catch 100 touchdown passes

© Getty Images

© REUTERS/Guglielmo Mangiapane

The 18-year-old Russian singer was arrested after her street performance of an anti-Putin song went viral

© REUTERS

President’s attorneys resurrect legal arguments to overturn jury’s verdict in a case that was ‘fatally marred’

© via REUTERS

© PA Wire

The Blues will be able to call on Liam Delap on Wednesday after two months out, although other injury issues persist

© PA Wire

The estate is fortified by high fences, with access restricted to security-controlled entry points

© Sophie Wingate/PA Wire

Compare over 60 licensed and regulated betting sites in the UK and read our reviews of the best online bookmakers for October 2025

© The Independent

Back-up Inter goalkeeper Martinez was on his way to training when an 81-year-old man in an electric wheelchair was struck and killed, with reports stating the elderly gentleman had a medical episode just prior to impact

© Getty Images

Prunella Scales played Sybil, the long-suffering wife of bumbling hotelier Basil Fawlty

© BBC

More than 100 investigators are racing to solve the daring heist at the Louvre Museum

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The achievement comes despite the company swallowing high costs from US tariffs

© ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images

Lawrence O’Donnell said that Scott Jennings wasn’t always like this, claiming he was once ‘capable’ of criticizing Trump before he ‘figured out where the money is’ and became the ‘JD Vance of CNN.’

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© MSNBC

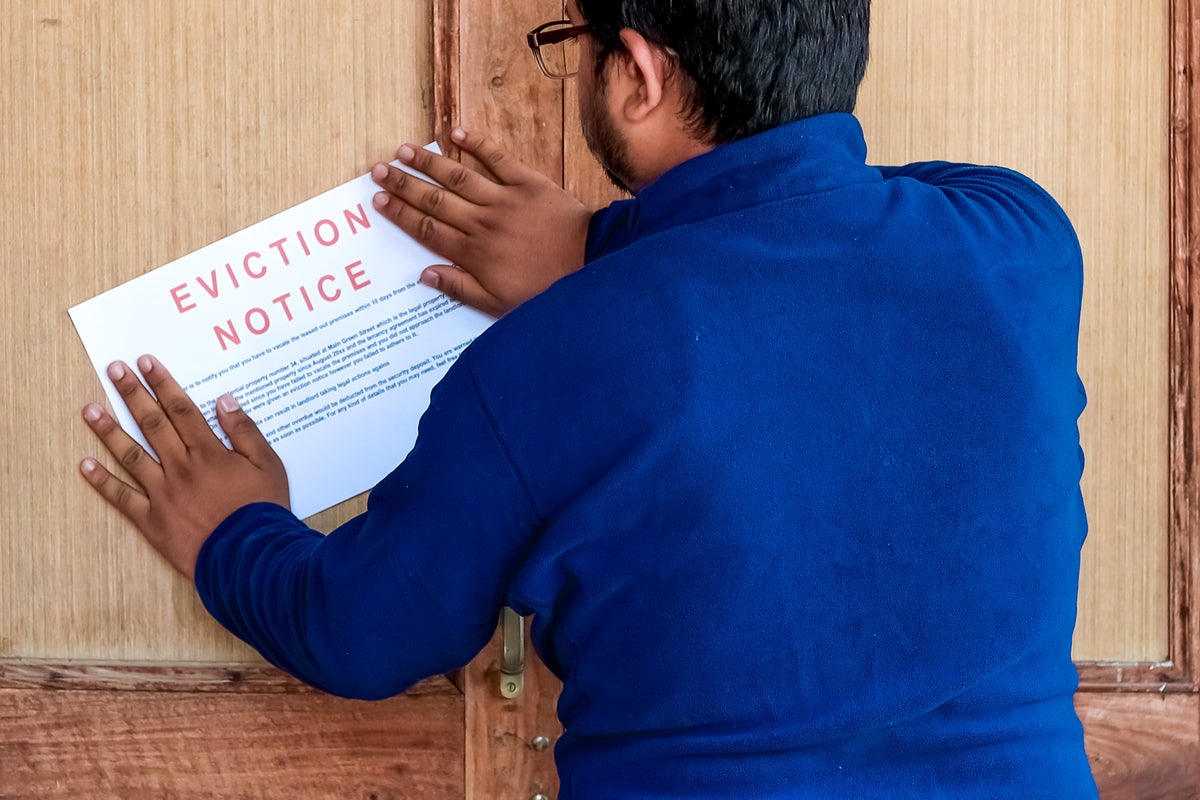

The new legislation is intended to improve the experience of private renting in England

© Getty

© Copyright 2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Danny Kruger, who defected from the Tories last month, has pledged a ‘more concentrated government machine’

© PA

Hyperhidrosis is a medical condition that affects one to three per cent of people in the UK

© BBC/Studio Lambert/Euan Cherry

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Freeman will shift from the wing to outside centre to face the Wallabies as George Ford wins the fly-half race

© Getty Images

More than 50 people killed in at least 13 strikes on 14 vessels as Trump administration escalates war against cartels

© Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth

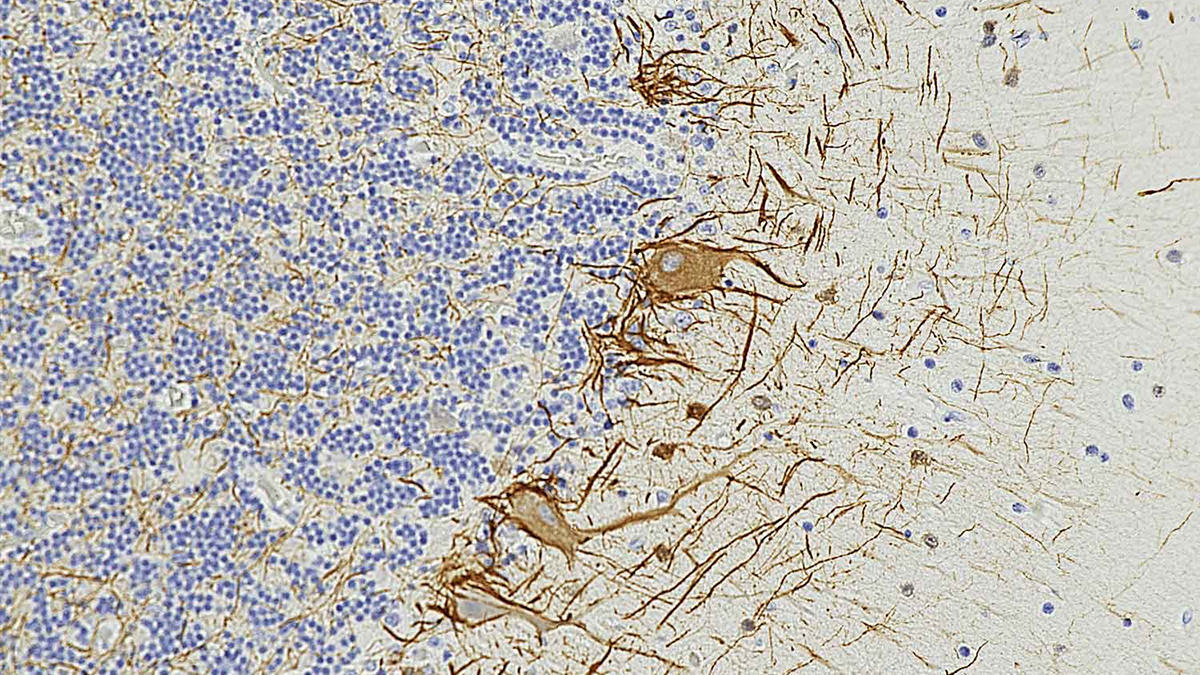

Discovery challenges the long-standing view of Homo habilis as the first skilled toolmaker

© Tiia Monto

Just before noon on a sunny Friday earlier this month, federal immigration agents threw tear gas canisters onto a busy Chicago street, just outside of an elementary school and a children’s play cafe.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The package of 24 energy drinks will be available in the U.S. on November 3

© Red Bull USA

Opposition leaders have alleged widespread fraud, accusations rejected by the government

© AP Photo/Welba Yamo Pascal

While numerous drivers cut the corner at turn two in Sunday’s Mexico GP, the moves went unpunished

© Getty Images

Lily Allen has shared a behind-the-scenes look at how she created her explosive new album, West End Girl — her first in seven years.

© Lily Allen

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The siblings performed during Game 2 of the 2025 World Series in Toronto

© Getty Images

© PA Media

Taking a page from other Republicans, the former collegiate swimmer accused Ocasio-Cortez and other progressive politicians of destroying the country

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

Although both men have since made amends, Groves is open to reigniting his rivalry with DeGale

© getty images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Erling Haaland’s goalscoring streak finally ended in the defeat by Aston Villa

© PA Wire

Republican-led panel claims former president’s ‘cognitive decline’ was so severe he may not have been aware what he was signing and his clemency orders are therefore ‘null and void’ and should be reviewed

© AP

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Comedian previously condemned Smith’s ‘sickening’ behavior, saying it was ‘gross’ that he wasn’t immediately escorted out of award show

© Getty

No injuries were reported in the scary incident

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© PA Wire

© Sputnik

© Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg via Getty Images

© gremlin | Getty Images

© Chef Yara Herrera

© Courtesy Dear Media

© StackCommerce

A new clinical trial has found that adding repeated intravenous ketamine infusions to standard care for hospitalized patients with serious depression did not provide a significant additional benefit. The study, which compared ketamine to a psychoactive placebo, suggests that previous estimates of the drug’s effectiveness might have been influenced by patient and clinician expectations. These findings were published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry.

Ketamine, originally developed as an anesthetic, has gained attention over the past two decades for its ability to produce rapid antidepressant effects in individuals who have not responded to conventional treatments. Unlike standard antidepressants that can take weeks to work, a single infusion of ketamine can sometimes lift mood within hours. A significant drawback, however, is that these benefits are often short-lived, typically fading within a week.

This has led to the widespread practice of administering a series of infusions to sustain the positive effects. A central challenge in studying ketamine is its distinct psychological effects, such as feelings of dissociation or detachment from reality. When compared to an inactive placebo like a saline solution, it is very easy for participants and researchers to know who received the active drug, potentially creating strong expectancy effects that can inflate the perceived benefits.

To address this, the researchers designed their study to use an “active” placebo, a drug called midazolam, which is a sedative that produces noticeable effects of its own, making it a more rigorous comparison.

“Ketamine has attracted a lot of interest as a rapidly-acting antidepressant but it has short-lived effects. Therefore, its usefulness is quite limited. Despite this major limitation, ketamine is increasingly being adopted as an off-label treatment for depression, especially in the USA,” said study author Declan McLoughlin, a professor at Trinity College Dublin.

“We hypothesized that repeated ketamine infusions may have more sustained benefit. So far this has been evaluated in only a small number of trials. Another problem is that few ketamine trials have used an adequate control condition to mask the obvious dissociative effects of ketamine, e.g. altered consciousness and perceptions of oneself and one’s environment.”

“To try address some of these issues, we conducted an independent investigator-led randomized trial (KARMA-Dep 2) to evaluate antidepressant efficacy, safety, cost-effectiveness, and quality of life during and after serial ketamine infusions when compared to a psychoactive comparison drug midazolam. Trial participants were randomized to receive up to eight infusions of either ketamine or midazolam, given over four weeks, in addition to all other aspects of usual inpatient care.”

The trial, conducted at an academic hospital in Dublin, Ireland, aimed to see if adding twice-weekly ketamine infusions to the usual comprehensive care provided to inpatients could improve depression outcomes. Researchers enrolled adults who had been voluntarily admitted to the hospital for moderate to severe depression. These participants were already receiving a range of treatments, including medication, various forms of therapy, and psychoeducation programs.

In this randomized, double-blind study, 65 participants were assigned to one of two groups. One group received intravenous ketamine infusions twice a week for up to four weeks, while the other group received intravenous midazolam on the same schedule. The doses were calculated based on body weight. The double-blind design meant that neither the patients, the clinicians rating their symptoms, nor the main investigators knew who was receiving which substance. Only the anesthesiologist administering the infusion knew the assignment, ensuring patient safety without influencing the results.

The primary measure of success was the change in participants’ depression scores, assessed using a standard clinical tool called the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale. This assessment was conducted at the beginning of the study and again 24 hours after the final infusion. The researchers also tracked other outcomes, such as self-reported symptoms, rates of response and remission, cognitive function, side effects, and overall quality of life.

After analyzing the data from 62 participants who completed the treatment phase, the study found no statistically significant difference in the main outcome between the two groups. Although patients in both groups showed improvement in their depressive symptoms during their hospital stay, the group receiving ketamine did not fare significantly better than the group receiving midazolam. The average reduction in depression scores was only slightly larger in the ketamine group, a difference that was small and could have been due to chance.

Similarly, there were no significant advantages for ketamine on secondary measures, including self-reported depression symptoms, cognitive performance, or long-term quality of life. While the rate of remission from depression was slightly higher in the ketamine group (about 44 percent) compared to the midazolam group (30 percent), this difference was not statistically robust. The treatments were found to be generally safe, though ketamine produced more dissociative experiences during the infusion, while midazolam produced more sedation.

“We found no significant difference between the two groups on our primary outcome measure (i.e. depression severity assessed with the commonly used Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)),” McLoughlin told PsyPost. “Nor did we find any difference between the two groups on any other secondary outcome or cost-effectiveness measure. Under rigorous clinical trial conditions, adjunctive ketamine provided no additional benefit to routine inpatient care during the initial treatment phase or the six-month follow-up period.”

A key finding emerged when the researchers checked how well the “blinding” had worked. They discovered that it was not very successful. From the very first infusion, the clinicians rating patient symptoms were able to guess with high accuracy who was receiving ketamine.

Patients in the ketamine group also became quite accurate at guessing their treatment over time. This functional unblinding complicates the interpretation of the results, as the small, nonsignificant trend favoring ketamine could be explained by the psychological effect of knowing one is receiving a treatment with a powerful reputation.

“Our initial hypothesis was that repeated ketamine infusions for people hospitalised with depression would improve mood outcomes,” McLoughlin said. “However, contrary to our hypothesis, we found this not to be the case. We suspect that functional unblinding (due to its obvious dissociative effects) has amplified the placebo effects of ketamine in previous trials. This is a major, often unacknowledged, problem with many recent trials in psychiatry evaluating ketamine, psychedelic, and brain stimulation therapies. Our trial highlights the importance of reporting the success, or lack thereof, of blinding in clinical trials.”

The study’s authors acknowledged some limitations. The research was unable to recruit its planned number of participants, partly due to logistical challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic. This smaller sample size reduced the study’s statistical power, making it harder to detect a real, but modest, difference between the treatments if one existed. The primary limitation, however, remains the challenge of blinding.

The results from this trial suggest that when tested under more rigorous conditions, the antidepressant benefit of repeated ketamine infusions may be smaller than suggested by earlier studies that used inactive placebos. The researchers propose that expectations for both patients and clinicians may play a substantial role in ketamine’s perceived effects. This highlights the need to recalibrate expectations for ketamine in clinical practice and for more robustly designed trials in psychiatry.

Looking forward, the researchers emphasize the importance of reporting negative or null trial results to provide a balanced view of a treatment’s capabilities. They also expressed concern about a separate in the field: the promotion of ketamine as an equally effective alternative to electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT.

“Scrutiny of the scientific literature shows that this includes methodologically flawed trials and invalid meta-analyses,” McLoughlin said. “We discuss this in some detail in a Comment piece just published in Lancet Psychiatry. Unfortunately, such errors have been accepted as scientific evidence and are already creeping into international clinical guidelines. There is a thus a real risk of patients and clinicians being steered towards a less effective treatment, particularly for patients with severe, sometimes life-threatening, depression.”

The study, “Serial Ketamine Infusions as Adjunctive Therapy to Inpatient Care for Depression: The KARMA-Dep 2 Randomized Clinical Trial,” was authored by Ana Jelovac, Cathal McCaffrey, Masashi Terao, Enda Shanahan, Emma Whooley, Kelly McDonagh, Sarah McDonogh, Orlaith Loughran, Ellie Shackleton, Anna Igoe, Sarah Thompson, Enas Mohamed, Duyen Nguyen, Ciaran O’Neill, Cathal Walsh, and Declan M. McLoughlin.

A new study suggests that higher levels of psychopathic traits are associated with lower relationship satisfaction in romantic couples. The research indicates that a person’s perception of their partner’s traits is a particularly strong predictor of their own discontent within the relationship. The findings were published in the Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy.

The research team was motivated by the established connection between personality and the quality of romantic relationships. While traits like agreeableness and conscientiousness are known to support relationship satisfaction, maladaptive traits, such as those associated with psychopathy, are understood to be detrimental. Psychopathy is not a single trait but a combination of characteristics, including interpersonal manipulation, a callous lack of empathy, an erratic lifestyle, and antisocial tendencies.

Previous studies have shown that individuals with more pronounced psychopathic traits tend to prefer short-term relationships, are more likely to be unfaithful, and may engage in controlling or destructive behaviors. Yet, much of this research did not simultaneously account for the perspectives of both partners in a relationship. The researchers aimed to provide a more nuanced understanding by examining how both a person’s own traits and their partner’s traits, as viewed by themselves and by their partner, collectively influence relationship satisfaction.

To investigate these dynamics, the researchers recruited a sample of 85 heterosexual couples from the Netherlands. The participants were predominantly young adults, many of whom were students. Each member of the couple independently completed a series of online questionnaires. The surveys were designed to measure their own psychopathic traits, their perception of their partner’s psychopathic traits, and their overall satisfaction with their relationship.

For measuring psychopathic traits, the study used a well-established questionnaire that assesses three primary facets: Interpersonal Manipulation (e.g., being charming but deceptive), Callous Affect (e.g., lacking guilt or empathy), and Erratic Lifestyle (e.g., impulsivity and irresponsibility). A fourth facet, Antisocial Tendencies, was excluded from the final analysis due to statistical unreliability within this specific sample. Participants completed one version of this questionnaire about themselves and a modified version about their romantic partner.

The researchers used a specialized statistical technique called the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model to analyze the data. This method is uniquely suited for studying couples because it can distinguish between two different kinds of influence. “Actor effects” refer to the association between an individual’s own characteristics and their own outcomes. For example, it can measure how your self-rated manipulativeness relates to your own relationship satisfaction. “Partner effects” describe the association between an individual’s characteristics and their partner’s outcomes, such as how your self-rated manipulativeness relates to your partner’s satisfaction.

Before conducting the main analysis, the researchers examined how partners’ ratings related to one another. They found very little “actual similarity,” meaning that a man’s level of psychopathic traits was not significantly related to his female partner’s level. However, they did find moderate “perceptual accuracy,” which means that how a person rated their partner was generally in line with how that partner rated themselves. There was also strong “perceptual similarity,” indicating that people tended to rate their partners in a way that was similar to how they rated themselves.

One notable preliminary finding was that both men and women tended to rate their partners as having lower levels of psychopathic traits than their partners reported for themselves. This could suggest a positive bias, where individuals maintain a more charitable view of their partner, or it may indicate that certain maladaptive traits are not easily observable to others in a relationship.

The central findings of the study emerged from the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. The most consistent result was a negative actor effect related to partner perception. When an individual rated their partner higher on psychopathic traits, that same individual reported lower satisfaction with the relationship. This connection was present for both men and women and held true across the total psychopathy score and its specific facets.

The study also identified other significant associations. For both men and women, rating oneself higher on Interpersonal Manipulation was linked to lower satisfaction in one’s own relationship. This suggests that a manipulative style may be unfulfilling even for the person exhibiting it.

A partner effect was observed for the trait of Callous Affect. When a person was perceived by their partner as being more callous, unemotional, and lacking in empathy, that partner reported lower relationship satisfaction. This highlights the direct interpersonal damage that a lack of emotional connection can inflict on a relationship.

In an unexpected turn, the analysis revealed one positive association. When women rated themselves as higher in Callous Affect, their male partners reported slightly higher levels of relationship satisfaction. The researchers propose that this could be related to gender stereotypes, where traits that might be labeled as callous in a clinical sense could be interpreted differently, perhaps as toughness or independence, in women by their male partners.

The study has some limitations that the authors acknowledge. The sample consisted of young, primarily student-based, heterosexual couples in relatively short-term relationships, which may not represent the dynamics in older, married, or more diverse couples. Because the study captured data at a single point in time, it cannot establish causality; it shows an association, not that psychopathic traits cause dissatisfaction. The sample size also meant the study was better equipped to detect medium-to-large effects, and smaller but still meaningful associations might have been missed.

Future research could build on these findings by studying larger and more diverse populations over a longer period. Following couples over time would help clarify how these personality dynamics affect relationship quality and stability as the relationship matures. A longitudinal approach could also determine if these traits predict relationship dissolution.

The study, “Psychopathic Traits and Relationship Satisfaction in Intimate Partners: A Dyadic Approach,” was authored by Frederica M. Martijn, Liam Cahill, Mieke Decuyper, and Katarzyna (Kasia) Uzieblo.

You can already save £40 on a pack of four AirTags, ahead of the sale

© The Independent

The job cuts are reportedly the first wave that could affect as many as 30,000 corporate jobs, which the Jeff Bezos-owned company boiled down to ‘staying nimble’

© AFP/Getty

Rodgers was accused of being ‘toxic’ and ‘divisive’ by Celtic chief Dermot Desmond in an explosive response to his resignation, which leaves an unlikely challenger in pole position for the Scottish title

© Getty Images

Benjamin Hiscox was working as a maths teacher when he engaged in an inappropriate sexual relationship with the child

© Google Maps

Exclusive: Son of British media tycoon welcomes US president’s promise to raise issue during Thursday’s landmark meeting

© AFP via Getty Images

Cook up delicious winter-warmers for less with this tried-and-tested appliance

© The Independent

As Caribbean sailings are affected by Hurricane Melissa, cruise expert Marc Shoffman explains how ships cope with extreme weather

© Getty Images

Actor was best known for playing the bossy wife to John Cleese’s eccentric hotelier Basil Fawlty in the acclaimed BBC sitcom

© Getty Images

© PA Wire

It is hoped that cloud-seeding over New Delhi will clear the city’s toxic air

© REUTERS

Fabio Wardley stopped Joseph Parker to produce a career-best upset win to become WBO interim heavyweight champion, but how did Wardley overcome someone with Parker’s wealth of experience?

© Queensberry/Leigh Dawney

Hamas and Israel continue to clash over the 13 bodies of hostages still held in Gaza

© X/@IsraelMFA

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

The 73-year-old will take charge on an interim basis alongside former player Shaun Maloney following Brendan Rodgers’ sudden departure

© Jonathan Brady/PA

‘Local theatre is where the real wizardry happens – sparking imagination and spreading a bit of joy,’ the Islington North MP said

© Pleasance Theatre

Prunella Scales reflected on how her marriage to Timothy West remained unchanged over 60 years in a moving 2023 interview.

© PA Archive

I tested the Surfshark VPN abroad for online safety and streaming Netflix – here's my review

© iStock/PonyWang/Surfshark

From Lidl to Laurent Perrier, these are the finest bubbles for any occasion

© Emma Henderson/The Independent

© Solano et al. (2024) via Scientific Reports

One mother saw her child benefit stop after a trip lasting less than 24 hours

© Getty Images

The prison staff at HMP fell for a fake email posing from the Royal Courts of Justice

© Getty

The Jamaican government has closed its international airports until further notice

© AP

Pimblett weighed in on his fellow Briton’s outing on Saturday, as Aspinall’s first undisputed title defence ended in concerning fashion

© AFP via Getty Images

© Copyright 2005 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The human chin has long been fertile ground for arguments between scientists over its purpose

© Getty/iStock

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The cousins are set for a rematch in Paris a couple of weeks after their fairytale final in Shanghai

© AFP via Getty Images

The long-awaited findings for the 2024 budget cap have been published by the sport’s governing body

© Getty Images

Bader - who had more than 200,000 followers - passed away in Miami, his girlfriend Reem said

© YouTube/ Ben Bader

Reality star was previously rushed to hospital with sepsis that led to liver and kidney failure

© E4

© PA Wire

Jamaica's prime minister implored residents to evacuate as Hurricane Melissa began lashing the island with violent gusts on Monday (October 27) as it approached landfall.

© Reuters

From ‘Captain America: The Winter Soldier’, right up to ‘Brave New World’

© Marvel Studios/Marvel/The Independent

What’s changed isn’t just when we celebrate but how: Halloween has evolved from a simple folk tradition to a commercial event

© AP

Enjoy a fun-filled day out for less with these Thorpe Park promo codes

.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Thorpe Park

Airline staff didn’t recognise Mark Spurr in his old photo after he shed 13 stone

Riads offer a serene escape from the bustling city, allowing guests to live among remarkable Moroccan craftsmanship and design

© Clemente Vergara

Experts do not expect US and China to resolve all their issues before the two presidents meet, but they are hoping for enough progress to stop the rivalry from doing more global economic damage. Alisha Rahaman Sarkar reports

© POOL/AFP/AFP via Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

In theory, if you consume fewer calories than you burn, you’ll lose weight. In practice, though, this isn’t as straightforward

© Getty/iStock

Grammer has four adult children from previous relationships and now four pre-teens with Walsh

© Getty

Experts crunched the numbers on a range of investment options to see how they have performed since 2010

© Getty/iStock

These winter sun destinations are perfect for beating the winter blues – and take only a few hours to fly to

© Getty Images

All you need to know about the best free spin no deposit offers at UK casinos

© Independent

Secretary of War continues campaign against facial hair on Pacific tour

© Getty

Uncapped speeds and low latency make this VPN ideal for online gaming

© The Independent

The former prime minister also warned the Tories must stop chasing the Reform party

© PA

Officials are at the scene investigating the cause of the crash

© REUTERS

It’s still possible to enjoy the UAE city with budget in mind, says Rebecca Black

© Getty/iStock

A downgrade in the productivity figures could leave Reeves with a bigger fiscal gap

© PA

‘They wouldn’t let me touch her. I’ll never forget that,’ says Christine Flack

© Getty Images

© PA Wire

Bella Culley was detained on drug trafficking charges earlier this year

© AP

Here’s how you can all get some shut-eye on the spookiest night of the year

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty/iStock

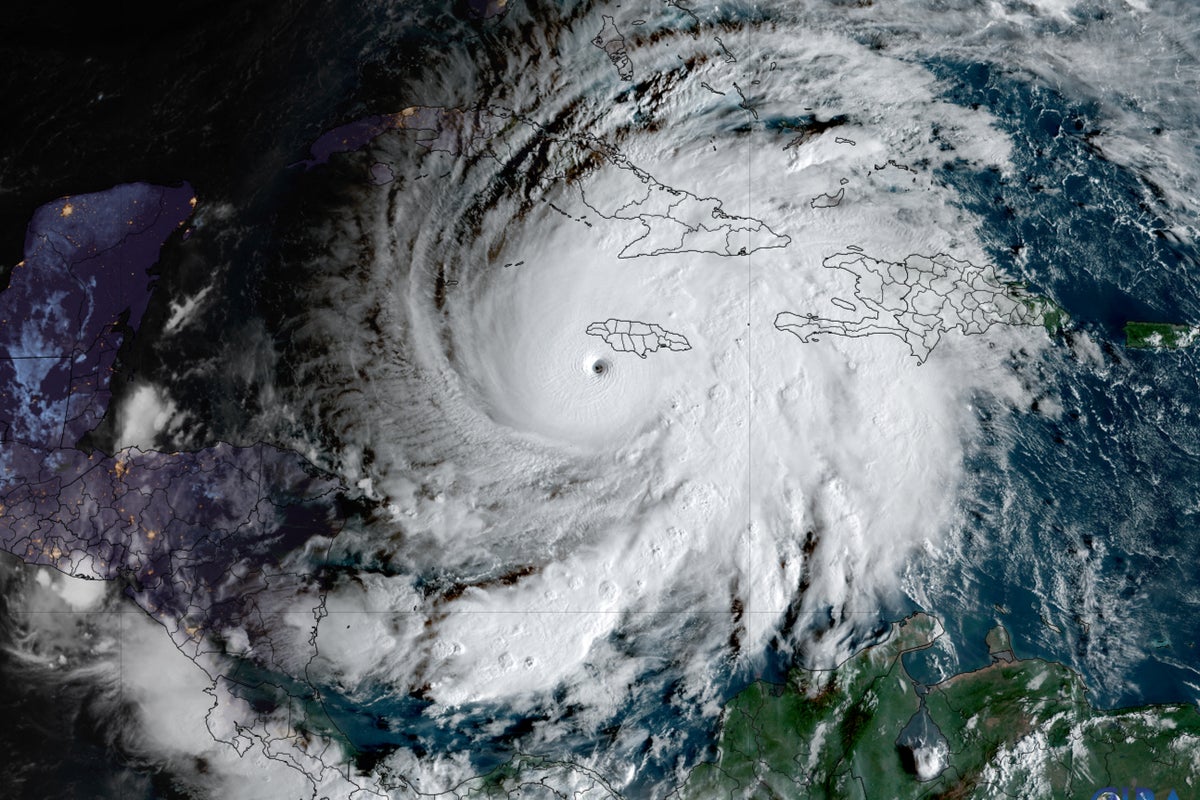

© VNA

Increasingly warm oceans resulting from global warming are a key reason for Hurricane Melissa's wind speed doubling in less than 24 hours over the weekend, climate scientists have said.

© NOAA

All the tranquility of a Caribbean holiday without the crowds, finds Sarah Marshall on a trip to Principe

© Alamy/PA

Side in Turkey is an increasingly popular place for a winter getaway

© Bijal/PA

© PA Wire

© 2025 The Associated Press.

Former Celtic star Chris Sutton has revealed who he thinks would be a “smart appointment” as the club’s new manager after the shock resignation of Brendan Rodgers.

© PA

A British holidaymaker trapped in Jamaica has described how there is an "undercurrent of panic" on the island as Hurricane Melisaa is set to make landfall on Tuesday (28 October).

© Sky

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Walking for 15 minutes a day continuously could cut he risk of cardiovascular disease by two thirds, study finds

© Getty Images

© 2025 The Associated Press

These versatile machines can also dry laundry at a lower cost than a tumble dryer

© Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The pagan festival of Samhain has been celebrated for at least 2,000 years

© Getty

The flagship wireless headphones from Sony could receive their biggest price cut so far this November

© The Independent

A new study indicates that Donald Trump’s frequent shrugging is a deliberate communication tool used to establish common ground with his audience and express negative evaluations of his opponents and their policies. The research, published in the journal Visual Communication, suggests these gestures are a key component of his populist performance style, helping him appear both ordinary and larger-than-life.

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the communication style of right-wing populism, which extends beyond spoken words to include physical performance. While a significant amount of analysis has focused on Donald Trump’s language, particularly on social media platforms, his live performances at rallies have received less systematic attention. The body is widely recognized as being important to political performance, but the specific gestures used are not always well understood.

This new research on shrugging builds on a previous study by one of the authors that examined Trump’s use of pointing gestures. That analysis found that Trump uses different kinds of points to serve distinct functions, such as pointing outwards to single out opponents, pointing inwards to emphasize his personal commitment, and pointing downwards to connect his message to the immediate location of his audience. The current study continues this investigation into his non-verbal communication by focusing on another of his signature moves, the shrug.

“The study was motivated by several factors,” explained Christopher Hart, a professor of linguistics at Lancaster University and the author of Language, Image, Gesture: The Cognitive Semiotics of Politics.

(1) Political scientists frequently refer to the more animated bodily performance of right wing populist politicians like Trump compared to non-populist leaders. We wanted to study one gesture – the shrug – that seemed to be implicated here. (2) Trump’s shrug gestures have been noted by the media previously and described as his “signature move”. We wanted to study this gesture in more detail to examine its precise forms and the way he uses it to fulfil rhetorical goals.”

“(3) To meet a gap: while a great deal has been written about Donald Trump’s speech and his use of language online, much less has been written about the gestures that accompany his speech in live settings. This is despite the known importance of gesture in political communication.”

To conduct their analysis, the researchers examined video footage of two of Trump’s campaign rallies from the 2016 primary season. The events, one in Dayton, Ohio, and the other in Buffalo, New York, amounted to approximately 110 minutes of data. The researchers adopted a conservative approach, identifying 187 clear instances of shrugging gestures across the two events.

Each shrug was coded based on its physical form and its communicative function. For the form, they classified shrugs based on the orientation of the forearms and the position of the hands relative to the body. They also noted whether the shrug was performed with one or two hands and whether it was a simple gesture or a more complex, animated movement. To understand the function, they analyzed the spoken words accompanying each shrug to determine the meaning being conveyed.

Hart was surprised “just how often Trump shrugs – 1.7 times per minute in the campaign rallies analyzed. Trump is a prolific shrugger and this is one way his communication style breaks with traditional forms of political communication.”

The analysis of the physical forms of the shrugs provided evidence for what has been described as a strong “corporeal presence.” Trump tended to favor expansive shrugs, with his hands positioned outside his shoulder width, a form that physically occupies more space.

The second most frequent type was the “lateral” shrug, where his arms extend out to his sides, sometimes in a highly theatrical, showman-like manner. This use of large, exaggerated gestures appears to contribute to a performance style more commonly associated with live entertainment than with traditional politics.

The researchers also noted that nearly a third of his shrugs were complex, meaning they involved animated, oscillating movements. These gestures create a dynamic and sometimes caricatured performance. While these expansive and animated shrugs help create an extraordinary, entertaining persona, the very act of shrugging is an informal, everyday gesture. This combination seems to allow Trump to simultaneously signal both his ordinariness and his exceptionalism.

When examining the functions of the shrugs, the researchers found that the most common meaning was not what many people might expect. While shrugs are often associated with expressing ignorance (“I don’t know”) or indifference (“I don’t care”), these were not their primary uses in Trump’s speeches. Instead, the most frequent function, accounting for over 44 percent of instances, was to signal common ground or obviousness. Trump often uses a shrug to present a statement as a self-evident truth that he and his audience already share.

For example, he would shrug when asking rhetorical questions like “We love our police. Do we love our police?” The gesture suggests the answer is obvious and that everyone in the room is in agreement. He also used these shrugs to present his own political skills as a given fact or to frame the shortcomings of his opponents as plainly evident to all. This use of shrugging appears to be a powerful tool for building a sense of shared knowledge and values with his supporters.

“Most people think of shrugs as conveying ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t care,” Hart told PsyPost. “While Trump uses shrugs to convey these meanings, more often he uses shrugs to indicate that something is known to everyone or obviously the case. This is one of the ways he establishes common ground and aligns himself with his audience, indicating that he and they hold a shared worldview.”

The second most common function was to express what the researchers term “affective distance.” This involves conveying negative emotions like disapproval, dissatisfaction, or dismay towards a particular state of affairs. When discussing trade deals he considered terrible or military situations he found lacking, a shrug would often accompany his words. In these cases, the gesture itself, rather than the explicit language, carried the negative emotional evaluation of the topic.

Shrugs that conveyed “epistemic distance,” meaning ignorance, doubt, or disbelief, accounted for about 17 percent of the total. A notable use of this function occurred during what is known as “constructed dialogue,” where Trump would re-enact conversations. In one instance, he used a mocking shrug while impersonating a political opponent to portray them as clueless and incompetent, a performance that drew laughter from the crowd.

The least common function was indifference, or the classic “I don’t care” meaning. Though infrequent, these shrugs served a strategic purpose. When shrugging alongside a phrase like “I understand that it might not be presidential. Who cares?,” Trump used the gesture to dismiss the conventions of traditional politics. This helps him position himself as an outsider who is not bound by the same rules as the political establishment.

The findings highlight that “what politicians do with their hands and other body parts is an important part of their message and their brand,” Hart told PsyPost. However, he emphasizes that “gestures are not ‘body language.’ They do not accidentally give away one’s emotional state. Gestures are built in to the language system and are part of the way we communicate. They carry part of the information speakers intend to convey and that information forms part of the message audiences take away.”

The study does have some limitations. Its analysis is focused exclusively on Donald Trump, so it remains unclear whether this pattern of shrugging is unique to his style or a broader feature of right-wing populist communication. Future research could compare his gestural profile to that of other populist and non-populist leaders.

Additionally, the study centered on one specific gesture, and a more complete picture would require analyzing the full range of a politician’s non-verbal repertoire. The authors also suggest that future work could examine other elements, like facial expressions and the timing of gestures, in greater detail.

Despite these limitations, the research provides a detailed look at how a seemingly simple gesture can be a sophisticated and versatile rhetorical tool. Trump’s shrugs appear to be a central part of a performance style that transgresses political norms, creates entertainment value, and forges a strong connection with his base. The findings indicate the importance of looking beyond a politician’s words to understand the full, embodied performance through which they communicate their message.

“We hope to look at other gestures of Trump to build a bigger picture of how he uses his body to distinguish himself from other politicians and to imbue his performances with entertainment value,” Hart said. This might include, for example, his use of chopping or slicing gestures. I also hope to explore the gestural performances of other right wing populist politicians in Europe to see how their gestures compare. ”

The study, “A shrug of the shoulders is a stance-taking act: The form-function interface of shrugs in the multimodal performance of Donald Trump,” was authored by Christopher Hart and Steve Strudwick.

![]() A full HD display on the tip of your finger.

A full HD display on the tip of your finger.

Steven van de Velde was convicted in 2016 and sentenced to four years in prison after admitting to raping a 12-year-old British girl he had met on social media

© Getty Images

Exclusive: The mayor of Liverpool would like to see visitor levies expanded across the city

© Getty Images

Interview: Cricket fans have questioned TNT Sports’ plan for the Ashes this winter, but the broadcaster’s voice of cycling, Rob Hatch, explains why he is the right man to helm the coverage

© TNT Sports

Exclusive: More than 6,000 children will be hit by shutdown after Labour said route was being manipulated by people-smuggling gangs

© PA

The government has suggesting closing hotels is a bid to appease the public but critics have said it will not save the taxpayer any money

© PA Wire

© PA Wire

Former Chelsea striker and his professional partner Lauren Oakley were voted off the competition on Sunday

© BBC

The family of Lindsay and Craig Foreman say the couple are ‘losing hope’

© Family handout

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© NDRF

© Alamy/PA

Shinzo Abe’s death shocked Japan, a country with some of the world’s strictest gun laws

© AP

Hearts have opened up an eight-point lead at the top of the Premiership, with O’Neill taking interim charge following the departure of Brendan Rodgers

© Talksport

© Alamy/PA

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The footage of the exchange has been widely circulated on social media

© PA Archive

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

In a a stunning statement, principal shareholder Dermot Desmond accused Rodgers of ‘false’ statements, ‘self-preservation’ tactics and ‘misleading’ behaviour that contributed to a ‘toxic atmosphere’

© REUTERS

© Eric Thayer/Getty Images

© PA Wire

The record-breaking storm is barreling toward Jamaica

© NOAA

© Kyodo News

Flaky filo, creamy mash and plenty of melted cheese – this month’s Budget Bites serves up comforting pies and bakes that prove hearty home cooking doesn’t have to come with a hefty price tag

© Sorted Food

HBO’s new Stephen King adaptation is completely watchable television, writes Louis Chilton – but part of a dispiriting trend that’s sweeping the industry

© HBO

© PA Archive

Yet Japan could face a big issue if the enormous vehicles are imported

© POOL/AFP via Getty Images

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

The Prince of Wales threatened to ‘re-examine’ the pair’s titles, new reports claim

© REUTERS

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Sean Grayson claims he shot Massey in self-defense after she told him she would ‘rebuke him in the name of Jesus’

© AP

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Chicago Sun-Times

© Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© AP

The Ukrainian president’s comments came as Donald Trump warned Putin that ‘we have a nuclear submarine off your shores’

© AFP/Getty

An appeals court earlier this month upheld an order pausing the threatened Guard operation in Illinois

© REUTERS

© Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Scholars of authoritarianism including Francis Fukuyama also asked the judge to throw out the charges, saying they were a clear example of an autocratic leader abusing the justice system to consolidate power

© J. Scott Applewhite

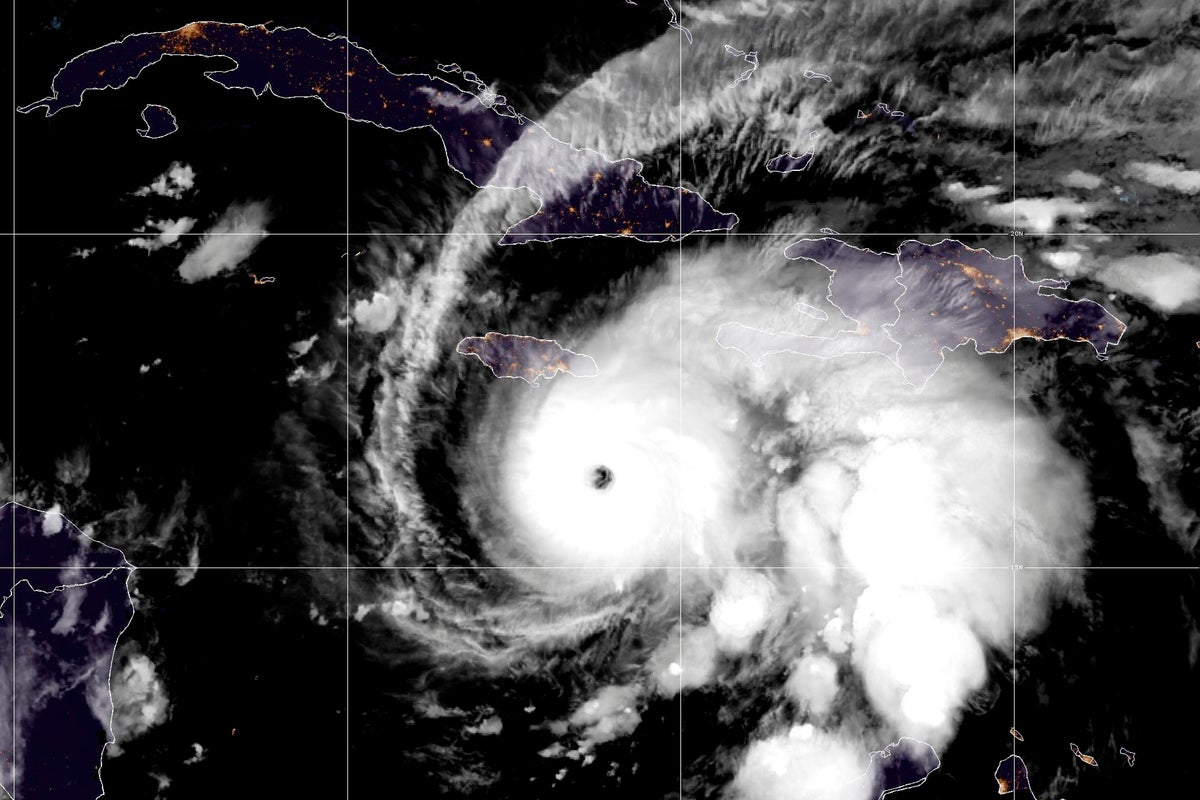

At least seven people have already been killed as the storm batters the Caribbean with heavy winds and torrential rainfall

© RAMMB/CIRA

© PA Archive

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The coming job cuts, reported to total around 2,000 workers, are part of an ongoing restructuring following the venerable entertainment company’s controversial merger this August

© Eric Thayer/Getty Images

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

A hidden condition that can strike without warning.

A hidden condition that can strike without warning.

“The future of computing could be fungal.”

“The future of computing could be fungal.”

'It could be a game-changer'.

'It could be a game-changer'.

© AP Photo/Jae C. Hong

The magnitude 6.1 quake was centered in the town of Sindirgi in Balikesir province

© AP

Despite their House majority, Republicans are poised to gain more seats through redistricting

© REUTERS

© Kevin Winter/Getty Images

© Joe Giddens/PA

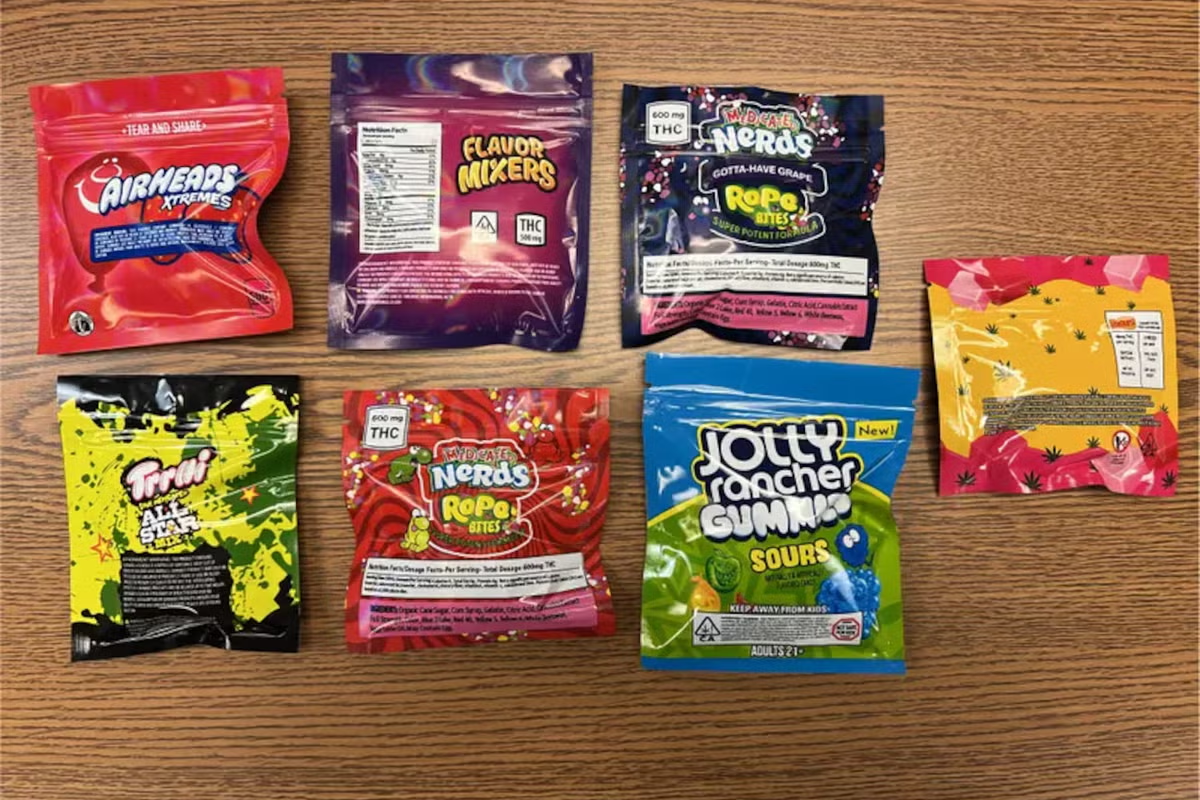

Experts say drug-laced Halloween candy is an urban legend, but police in Warren, Michigan said the

© Warren Police Department

Communities continue to be denied vital amenities such as GP surgeries and schools because of flaws in processes intended to secure fair financial contributions from developers

© Steve Parsons/PA

© PA Wire

Jamie Scott has been fundraising for life-extending treatment through bake sales

© OMUK/PA

Peers said they were “unimpressed with the lack of interest shown by the police” when it came to tackling serious and organised waste crime

© PA

© PA Wire

Researchers say looking at original works of art can help immediately relieve stress

© Getty/iStock

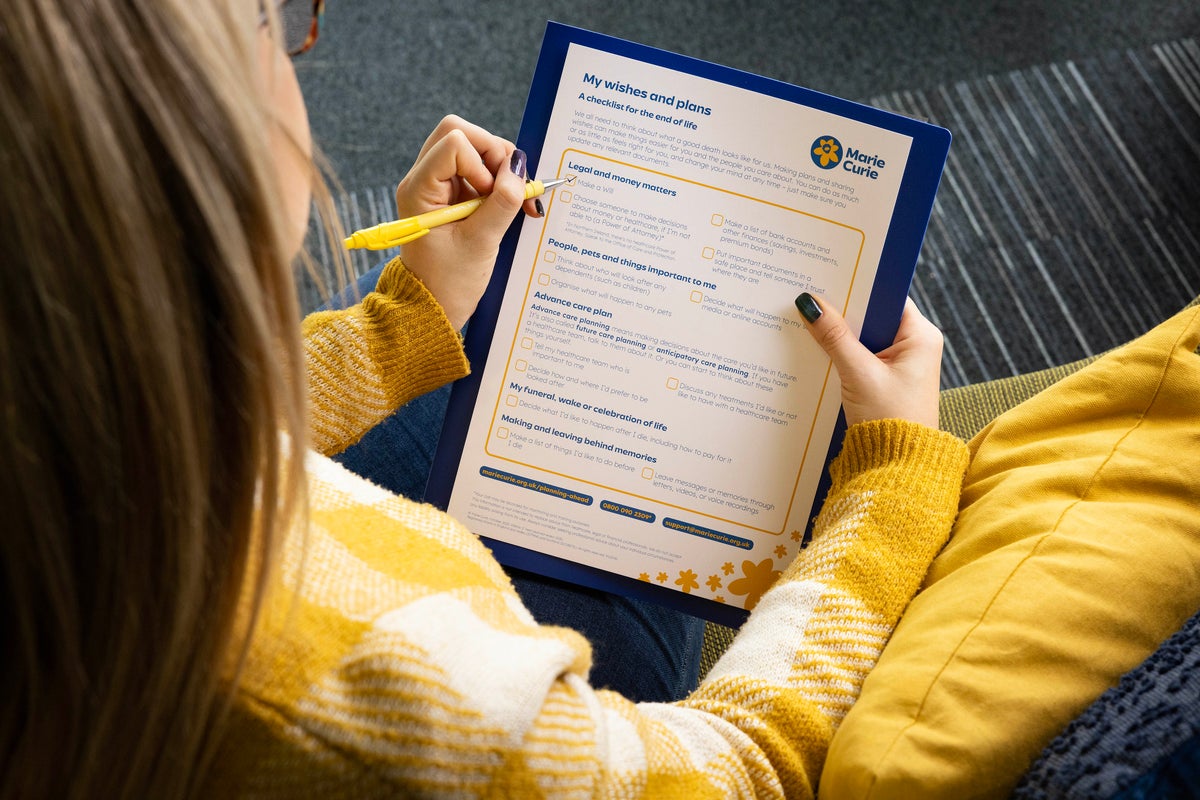

The list, curated by clinicians, covers everything from wills to wakes and what we might want to happen to pets

© PA

Consumers struggling with cost of living crisis now also face fresh wave of so-called shrinkflation

© PA

Maison was diagnosed with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) at the age of one

© Family Handout

Letters will be dropping on doormats across England and Wales from Tuesday

© PA Wire

Jordan's Queen Rania has praised Donald Trump for his 20-point peace plan for Gaza.

© BBC

New South Wales Premier Chris Minns said the incident was a ‘sobering reminder’ of the industry's dangers

© Lisa Maree Williams/Getty Images

The federal workers’ union said the Senate needs to pass a clean continuing resolution. Republicans say Democrats ‘need to listen to the unions, and that's not a sentence I say very often’

© Getty Images

Breach could also allow hackers to access logins associated with email accounts

© Getty/iStock

Watch the moment a dog is rescued by police officers from a storm drain in New Jersey.

© Wall Township Police Department

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Atlanta-based Carter’s said it expected to pay up to $250 million this year in extra costs due to President Donald Trump’s taxes on foreign imports

© Google Earth

Satellite imagery shows the “monster” eye of Hurricane Melissa, the most powerful storm recorded this year, that is currently hurtling towards Jamaica.

© CIRA

Whether you’re looking for an electric diffuser or a reed diffuser, I’ve found the best options

© Siobhan Grogan/The Independent

© REUTERS/Mike Segar

© Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

Editorial: Billions have been wasted on unfit accommodation that suits neither the migrants who shelter there nor the communities enraged by their presence. It is imperative that the government take decisive steps and build an alternative – now

© AP

The incident occurred on Delta flight 3248 from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Salt Lake City, Utah

© Reddit user Wiley

A double murderer took four children to McDonald’s just hours after killing their parents.

© Sussex Police

A new study proposes that horror films are appealing because they offer a controlled environment for our brains to practice predicting and managing uncertainty. This process of learning to master fear-inducing situations can be an inherently rewarding experience, according to the paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

The authors behind the paper, published in 2013, sought to address why people are drawn to entertainment that is designed to be frightening or disgusting. While some studies have shown psychological benefits from engaging with horror, many existing theories about its appeal seem to contradict one another. The authors aimed to provide a single, unifying framework that could explain how intentionally seeking out negative feelings like fear can result in positive psychological outcomes.

To do this, they applied a theory of brain function known as predictive processing. This framework suggests the brain operates as a prediction engine, constantly making forecasts about incoming sensory information from the world. When reality does not match the brain’s prediction, a “prediction error” occurs, which the brain then works to minimize by updating its internal models or by acting on the world to make it more predictable.

This does not mean humans always seek out calm and predictable situations. The theory suggests people are motivated to find optimal opportunities for learning, which often lie at the edge of their understanding. The brain is not just sensitive to the amount of prediction error, but to the rate at which that error is reduced over time. When we reduce uncertainty faster than we expected, it generates a positive feeling.

This search for the ideal rate of error reduction is what drives curiosity and play. We are naturally drawn to a “Goldilocks zone” of manageable uncertainty that is neither too boringly simple nor too chaotically complex. The researchers argue that horror entertainment is specifically engineered to place its audience within this zone.

According to the theory, horror films can be understood as a form of “affective technology,” designed to manipulate our predictive minds. Even though we know the monsters are not real, the brain processes the film as an improbable version of reality from which it can still learn. Many horror monsters tap into deep-seated, evolutionary fears of predators by featuring sharp teeth, claws, and stealthy, ambush-style behaviors.

The narrative structures of horror films are also built to play with our expectations. The slow build-up of suspense creates a state of high anticipation, and a “jump scare” works by suddenly violating our moment-to-moment predictions. The effectiveness of these techniques is heightened because they are not always predictable. Sometimes the suspense builds and nothing happens, which makes the audience’s response system even more alert.

At the same time, horror films often rely on familiar patterns and clichés, such as the “final girl” who survives to confront the villain. This combination of surprising events within a somewhat predictable structure provides the mix of uncertainty and resolvability that the predictive brain finds so engaging.

The authors propose that engaging with this controlled uncertainty has several benefits. One is that horror provides a low-stakes training ground for learning about high-stakes situations. This idea, known as morbid curiosity, suggests that we watch frightening content to gain information that could be useful for recognizing and avoiding real-world dangers. For example, the film Contagion saw a surge in popularity during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, as people sought to understand the potential realities of a global health crisis.

Another benefit is related to emotion regulation. By exposing ourselves to fear in a safe context, we can learn about our own psychological and physiological responses. The experience allows us to observe our own anxiety, increased heart rate, and other reactions as objects of attention, rather than just being swept away by them. This process can grant us a greater sense of awareness and control over our own emotional states, similar to the effects of mindfulness practices.

The theory also offers an explanation for why some people prone to anxiety might be drawn to horror. Anxiety can be associated with a feeling of uncertainty about one’s own internal bodily signals, a state known as noisy interoception. Watching a horror movie provides a clear, external source for feelings of fear and anxiety. For a short time, the rapid heartbeat and sweaty palms have an obvious and controllable cause: the monster on the screen, not some unknown internal turmoil.

The researchers note that this engagement is not always beneficial. For some individuals, particularly those with a history of trauma, horror media may serve to confirm negative beliefs about the world being a dangerous and threatening place. This can create a feedback loop where a person repeatedly seeks out horrifying content, reinforcing a sense of hopelessness or learned helplessness. Future work could examine when the engagement with scary media crosses from a healthy learning experience into a potentially pathological pattern.

The study, “Surfing uncertainty with screams: predictive processing, error dynamics and horror films,” was authored by Mark Miller, Ben White and Coltan Scrivner.

Rodgers’ second stint at Celtic Park ends in resignation with the club eight points adrift of top spot

© PA Wire

© PA Wire

I spent four months testing the multifunctional pans in my own kitchen

© Kate Ng/The Independent

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The judge denied Robinson's request to appear without restraints

© Utah Governor's Office

© Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Halloween can be a time to grab more than just free candy

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty/iStock

© Albanian Prime Minister's Office

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

‘Sure, at first blush it sounds crazy, but Trump loves a deal, and Brian Roberts needs to think big and differently,’ media analyst Rich Greenfield wrote this week

© Getty Images

King Charles was heckled by a protester who asked the monarch about Prince Andrew’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein.

© Sky News

The recall was issued in two states

© Getty Images

The likes of BrewDog and Black Sheep Brewery have us fizzing with excitement

© Tamara Hinson/Woodforde's/The Independent

Platner, an oyster farmer and populist running for Senate in Maine, has faced multiple controversies in recent weeks over his past views and a controversial skull-and-bones tattoo reminiscent of Nazi imagery

© AP

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© PA Archive

Newly released docs reveal Chelsea Berg confronted her boyfriend about her son’s bruises a month before he was hospitalized

© Collin County Jail

Craig Revel Horwood delivered a scathing remark to one Strictly Come Dancing contestant, calling her dancing “dull”.

© BBC

This figure represents nearly 10 percent of its approximately 350,000 corporate staff

© Peter Byrne/P

The Independent has previously spoken to survivors who faced the impossible choice of remaining in debt or risking their abusers finding out where they live

© Getty/iStock

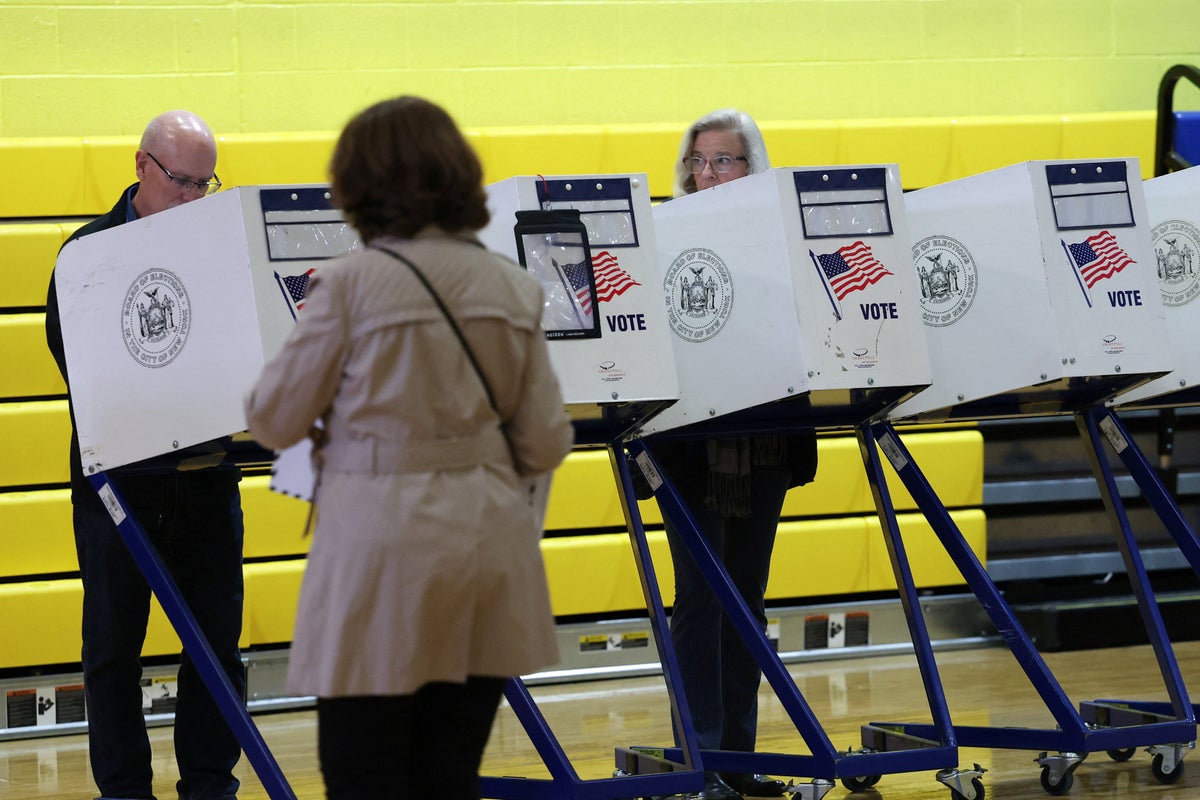

President challenges legitimacy of ballots that are not cast in person on election day as Republicans brace for 2026

© Getty

The spice has a shelf life of up to four years

© Getty/iStock

Tesla’s board has received some criticism over its apparent close relationship with Musk, the company’s CEO

© AP

The findings come as doctors work to understand why rates of early cancer are rising in younger adults

© Getty

Sweeney recalled some of the comments she received while auditioning as a young actor

© Getty

The Roomba creator has been sliding towards disaster since January 2024, when Amazon pulled out of a planned acquisition deal

© Getty

A new UKHSA report said 16 cases of the ‘clade Ib’ mpox strain have been reported in England

© PA

The suspected armed robbers targeted a home in Jurupa Valley, California

© Getty/iStock

The study found that nearly 30 percent of stillbirths occur in pregnancies where there were no known risk factors

© PA

Experts say not to worry if your pumpkin’s been sitting on the porch all month

© Getty/iStock

© JOHN GURZINSKI / AFP via Getty Images

President’s allies say deficit is going down, but predictions for 2026 still range as high as $2.2 trillion

© Getty Images

Canadian singer said, ‘Accounts shud be suspended for body shaming en masse’

© Getty

© Russian Defence Ministry

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Their first meeting came over 10 years ago, with Mayweather beating Pacquiao on the scorecards

© AP

The director of public prosecutions said the failure to describe China as an active threat to national security was ‘fatal’ to the case

© Parliament TV

The world’s first AI minister is “pregnant with 83 children”, Albania’s prime minister has announced.

© Albanian Prime Minister's Office

Crawford’s willingness to embrace tough tests makes him a better fighter than Mayweather according to boxing royalty

© Getty

Rather than responding immediately to the call, police sergeant Kevin Bollaro allegedly drove two miles in the opposite direction and stopped to get cash and a slice

© Google Maps

Strictly Come Dancing's Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink fought back tears as he spoke out for the first time after leaving the BBC show.

© BBC

© Instagram/@jackdejohnette_

Former IFS director Paul Johnson says a mansion tax ‘wouldn’t raise anywhere near enough to fill a significant hole’ in the public finances

© Jordan Pettitt/PA Wire

A Louvre security guard has described how he found a £10m royal crown on the floor outside the museum, after four thieves wielding power tools broke into the building in broad daylight.

© AFP via Getty Images

Wardley’s stoppage win has split opinion, as Parker was ahead on points with a round-and-a-half left

© PA Wire

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Vinicius stormed down the tunnel following his substitution before re-emerging at full-time to confront the Barcelona players

© REUTERS

Atkinson had disclosed symptoms consistent with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in a 2016 interview

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

‘We’re dealing with what’s possibly a serial killer,’ investigators said

© Wood County Sheriff's Office/FindJodi.com/Wood County Sheriff

Arlene Phillips has named Hannah Waddingham as a new potential Strictly Come Dancing host to replace Claudia Winkleman and Tess Daly, naming the actor as both “fun” and “super smart”.

© ITV

Muniz first met Duff alongside her mother on the set of the Disney Channel sitcom, ‘Lizzie McGuire’

© Getty Images

Sheffield Wednesday’s joint administrator has said there are already “four or five” viable potential buyers

© PA Wire

© AP Photo/Charlie Riedel, File

© Starling Bank

The star-studded drama recently finished shooting in France

© Getty Images

© Getty Images

© miniseries | Getty Images

A new longitudinal study suggests that intimate partners mutually influence each other’s support for political parties over time. The research found that a shift in one person’s support for a party was predictive of a similar shift in their partner’s support the following year, a process that may contribute to political alignment within couples and broader societal polarization. The findings were published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin/em>.

Political preferences are often similar within families, particularly between parents and children. However, less is known about how political views might be shaped during adulthood, especially within the context of a long-term romantic relationship. Prior studies have shown that partners often hold similar political beliefs, but it has been difficult to determine if this is because people choose partners who already agree with them or if they gradually influence each other over the years.

The authors of the new study sought to examine if this similarity is a result of ongoing influence. They wanted to test whether a change in one partner’s political stance could predict a future change in the other’s. To do this, they used a large dataset from New Zealand, a country with a multi-party system. This setting allowed them to see if any influence was specific to one or two major parties or if it occurred across a wider ideological spectrum, including smaller parties focused on issues like environmentalism, indigenous rights, and libertarianism.

To conduct their investigation, the researchers analyzed data from the New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study, a large-scale project that has tracked thousands of individuals over many years. Their analysis focused on 1,613 woman-man couples who participated in the study for up to 10 consecutive years. Participants annually rated their level of support for six different political parties on a scale from one (strongly oppose) to seven (strongly support).

The study employed a sophisticated statistical model designed for longitudinal data from couples. This technique allowed the researchers to separate two different aspects of a person’s political support. First, it identified each individual’s stable, long-term average level of support for a given party. Second, it isolated the small, year-to-year fluctuations or deviations from that personal average. This separation is important because it allows for a more precise test of influence over time.

The analysis then examined whether a fluctuation in one partner’s party support in a given year could predict a similar fluctuation in the other partner’s support in the subsequent year. This was done while accounting for the fact that couples already tend to have similar average levels of support.

The results showed a consistent pattern of mutual influence. For all six political parties examined, a temporary increase in one partner’s support for that party was associated with a subsequent increase in the other partner’s support one year later. This finding suggests that partners are not just politically similar from the start of their relationship but continue to shape one another’s specific party preferences over time.

This influence also appeared to be a two-way street. The researchers tested whether men had a stronger effect on women’s views or if the reverse was true. They found that the strength of influence was generally equal between partners. With only one exception, the effect of men on women’s party support was just as strong as the effect of women on men’s support.

The single exception involved the libertarian Association of Consumers and Taxpayers Party, where men’s changing support had a slightly stronger influence on women’s subsequent support than the other way around. For the other five parties, including the two largest and three other smaller parties, the influence was symmetrical. This challenges the idea that one partner, typically the man, is the primary driver of a couple’s political identity.

An additional analysis explored whether this dynamic of influence applied to a person’s general political orientation, which was measured on a scale from extremely liberal to extremely conservative. In this case, the pattern was different. While partners tended to be similar in their overall political orientation, changes in one partner’s self-rated orientation did not predict changes in the other’s over time. This suggests that the influence partners have on each other may be more about support for specific parties and their platforms than about shifting a person’s fundamental ideological identity.

The researchers acknowledge some limitations of their work. The study focused on established, long-term, cohabiting couples in New Zealand, so the findings may not apply to all types of relationships or to couples in other countries with different political systems. Because the couples were already in established relationships, the study also cannot entirely separate the effects of ongoing influence from the possibility that people initially select partners who are politically similar to them.

Future research could explore these dynamics in newer relationships to better understand the interplay between partner selection and later influence. Additional studies could also investigate the specific mechanisms of this influence, such as how political discussions, media consumption, or conflict avoidance might play a role in this process. Examining whether these shifts in expressed support translate to actual behaviors like voting is another important avenue for exploration.

The study, “The Interpersonal Transmission of Political Party Support in Intimate Relationships,” was authored by Sam Fluit, Nickola C. Overall, Danny Osborne, Matthew D. Hammond, and Chris G. Sibley.

The Maranello brand’s first NFT car channels aerodynamics and AI design into a virtual racing icon, but is it a car?

© Ferrari

A closer look at the first digital Ferrari.

© Ferrari

With a new token aimed at elite collectors, Ferrari gives tech-savvy fans a digital stake in its legendary endurance car.

© Ferrari

The latest FSD update promises faster lane changes and bolder driving behavior—just as NHTSA deepens its safety probe.

© Anna Barclay

© Eric Hartline-Imagn Images/File Photo

Franke was attending a wedding in the Dominican Republic when he died, his colleague said

© Barstool Sports

© Getty Images/iStockphoto

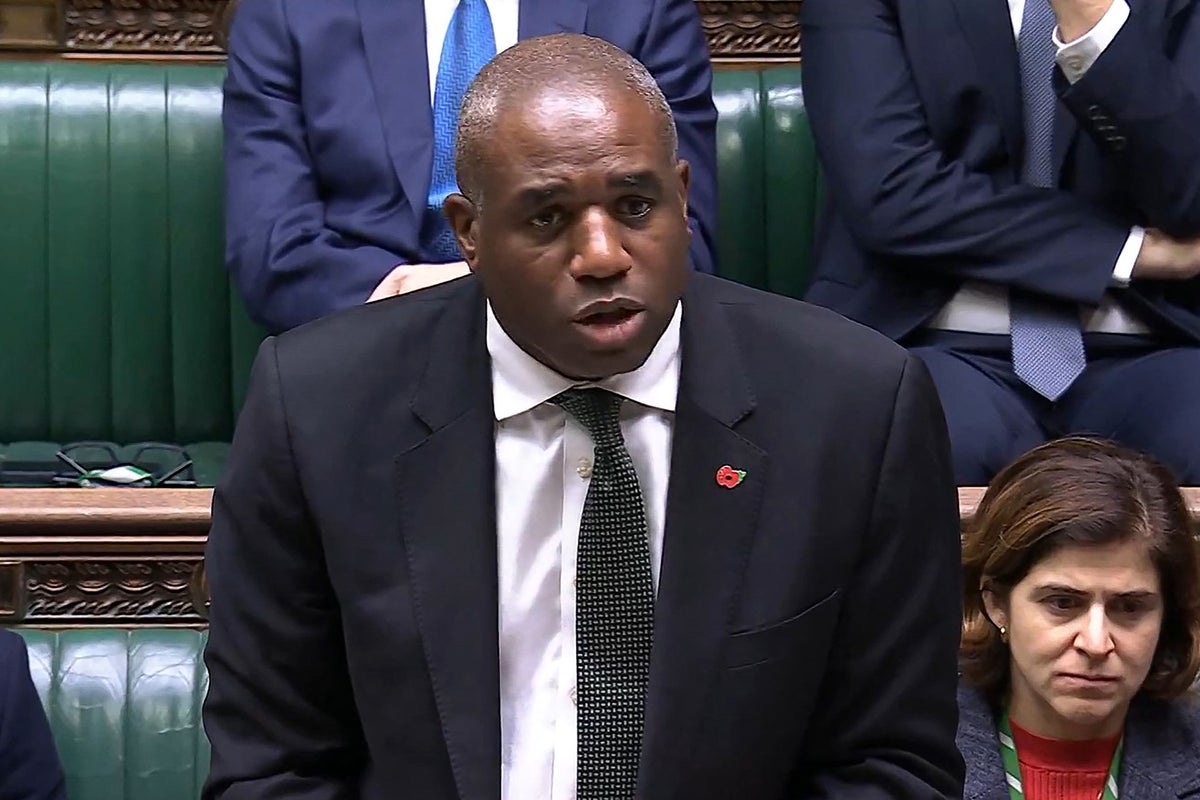

Justice secretary David Lammy pledges release checks on foreign inmates will be tightened

© PRU

This is a photo gallery curated by AP photo editors.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Samet Yalcin/Dia Photo via AP

Mat Kelly is urging all men to ‘check their chests’

© Collect/PA Real Life

Exclusive: Desailly tells The Independent why he does not blame fellow Chelsea great Hazard for ending his career prematurely

© Chelsea FC via Getty Images

Paul Gascoigne has described his involvement in the Raoul Moat manhunt as the “biggest regret” of his life.

© PA Archive

The first attempts at using pig organs in humans were short-lived

© Getty/iStock

The president’s plans for the historic East Wing, which has been partly demolished to make way for a lavish new, $300 million ballroom, has faced fierce criticism

© The Glenn Beck Show

Cities like Atlanta and Denver offer you the most space when buying a luxury mansion

© Getty Images

© Barstool Sports

With no aircraft, no ticket sales and all flights cancelled, it seems unlikely the airline can be rescued

© Eastern Airways

A Kentucky trooper was shot by a gunman during a traffic stop but was saved thanks to the quick actions of a group of Good Samaritans.

© Kentucky State Police

© Getty/iStock

Turkey’s football federation will launch disciplinary action after 371 referees were found to have betting accounts

© AFP via Getty Images

© Orlando Sentinel

‘He’s an excellent journalist, good human being, and someone you want in a newsroom,’ one staffer told The Independent about Dickerson’s pending departure.

© PA Archive

© PA Archive

© Alessandro Garofalo/LaPresse vía AP

© AP Photo/David Zalubowski

Hailey Bieber has shown support for her friend Kendall Jenner during the Vogue World: Hollywood fashion show.

© Hailey Bieber

Pop star, who is currently on her Bite Me tour, said her body has ‘finally given out’

© Getty Images

Deck your kids out in spooky attire for less this Halloween

© iStock

The singer’s father was previously married to Sheri Easterling in 2004 and then again in 2017

© Getty Images

The agreement is the largest fighter jet deal in almost 20 years and the first new order for UK Typhoons since 2017

© PA

You’ll soon be able to save on everything from iPhones to MacBooks in the Black Friday sale

© The Independent

You don’t need to spend hours in the salon

© L'Oréal/The Independent

‘Gavin Newsom cares more about giving illegals commercial drivers licenses than he does citizens of his own state and the safety of Americans. It’s shameful,’ Sean Duffy says

© Getty

David Lammy has accused Robert Jenrick of having a “brass neck” over comments made about a mistakenly released migrant sex offender.

-copy.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Parliament TV

Every Friday Jonathan Doidge’s Independent Racing newsletter will bring you the inside track on the sport: what to watch out for, who’s in form, and which horses might just be worth keeping an eye on

© Independent

© PA Wire

The ‘aggressive’ insects can spread dengue, zika and other life-threatening viral illnesses

© CDC

© Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Leon Bennett/Getty Images for Critics Choice Association

Vulnerable women were plied with ‘unlimited supply’ of crack cocaine and whisky

© Police Scotland/PA

First lady has maintainted public silence over $350m White House ballroom but reportedly ‘raised concerns’ in private and denied responsibility for the project

© Reuters

Coronation Street’s Lucy Fallon says she had to rush her baby daughter to A&E following a series of sinus infections.

© Lucy Fallon

The woman won the ticket simply after walking into a convenience store after work and managed to beat the odds

© Getty/iStock

Jones retired instead of defending the heavyweight title against Aspinall, who put it on the line against Ciryl Gane – only to suffer a fight-ending foul

© Getty

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

New season sees Liam Hemsworth replace Henry Cavill as Geralt of Rivia

© Netflix

Solar panels are more affordable than ever, but prices still vary depending on your system size, roof type, and energy goals. Here’s what you need to know

© iStock/The Independent

The statue has long been controversial and even “stirred opposition” when it was planned over 100 years ago

© Reuters

The bill seeks to end the practice of ‘rental bidding’, where landlords can effectively maximise the rent they receive.

© Getty Images/iStockphoto

© Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

After a no show in last year’s sale, I’m hoping this year’s Xbox Black Friday bargains will be the best yet

© The Independent

Whether it's a week or more by the beach or wandering the streets of the Lion City, these are the best hotels in Singapore to book on your next break

© Georg Roske

© Copyright 2018. The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

We’ve been implicitly instructed for a lifetime that the only way to ‘win’ when grieving a broken heart is to handle it gracefully. But ‘West End Girl’ is showing women everywhere that unleashing our anger can actually be a superpower, writes Helen Coffey

© Getty

Up to 50 per cent off tickets and 20 per cent off hotels with Legoland Windsor promo codes

.png?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Legoland

© PA Wire

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© From the Lesley & Rhyan Prather Foundation

Errors such as accidental release of Hadush Kebatu, who was imprisoned for sexually assaulting a 14-year-old girl, are symptomatic of ‘chaos’ in criminal justice system

© Crown Prosecution Service

The annual sales event will be with us in one month

© CeraVe/Kate Somerville/Color Wow/Lancome/The Inkey List/The Independent

These are the best townhouses, hostels and boutique stays available for under £120 per night in the beautiful Georgian city

© The Kennard

One consulting firm recently laid off 11,000 employees, and it’s not alone

© Sutthiphong - stock.adobe.com

© Getty/iStock

Hindu devotees are gathering at rivers and bodies of water across India to pray to the sun god, Lord Surya, as part of the Chhath festival this week.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Staff shortages have increased four times over October 2024 as a federal government shutdown nears its one-month anniversary

© AFP via Getty Images

Cheyenne Sears, 25, was traveling southbound on State Road 67, about 40 miles southwest of Indianapolis Saturday when her vehicle was hit

© Lesley & Rhyan Prather Foundation

Kim Wiltshire and her children found peace and tranquility in the little-known Ria Formosa lagoon

© Getty Images/iStockphoto

Up until now, most of the American public has been insulated from the shutdown’s effects, Eric Garcia writes. But with SNAP recipients going hungry, labor groups demanding the government reopen and ongoing health insurance enrollment, Trump and Democrats might be forced to find a solution.

© AFP via Getty Images

Ingebrigtsen endured an injury-hit 2025 but is dreaming big for next season

© Getty Images

Makhachev was expected to square off against Topuria before he moved up to welterweight

© USA TODAY Sports via Reuters Con

Cyber experts believe digital IDs could be targeted if your phone is stolen

© Alamy/PA

© V3rc4 | Shutterstock

© Andy Ryan | Getty Images

© Richard Drury | Getty Images

© Courtesy of Cassavida

A new study suggests that individuals who leave their religion tend to become more politically liberal, often adopting views similar to those who have never been religious. This research, published in the Journal of Personality, provides evidence that the lingering effects of a religious upbringing may not extend to a person’s overall political orientation. The findings indicate a potential boundary for a psychological phenomenon known as “religious residue.”

Researchers conducted this study to investigate a concept called religious residue. This is the idea that certain aspects of a person’s former religion, such as specific beliefs, behaviors, or moral attitudes, can persist even after they no longer identify with that faith. Previous work has shown that these lingering effects can be seen in areas like moral values and consumer habits, where formerly religious people, often called “religious dones,” continue to resemble currently religious individuals more than those who have never been religious.

The research team wanted to determine if this pattern of residue also applied to political orientation. Given the strong link between religiosity and political conservatism in many cultures, it was an open question what would happen to a person’s politics after leaving their faith. They considered three main possibilities. One was that religious residue would hold, meaning religious dones would remain relatively conservative.

Another possibility was that they would undergo a “religious departure,” shifting to a liberal orientation similar to the never-religious. A third option was “religious reactance,” where they might react against their past by becoming even more liberal than those who were never religious.

To explore these possibilities, the researchers analyzed data from eight different samples across three multi-part studies. The first part involved a series of six cross-sectional analyses, which provide a snapshot in time. These studies included a total of 7,089 adults from the United States, the Netherlands, and Hong Kong. Participants were asked to identify as currently religious, formerly religious, or never religious, and to rate their political orientation on a scale from conservative to liberal.