‘King of K-pop’ Lee Soo Man on his career, a global industry and what’s next

© Invision

© Invision

Nearly two decades after the chilling discovery of mutilated bodies in drains behind a bungalow in a village near Delhi, India’s top court is now poised to overturn the last remaining conviction in the serial murder case. Speaking to Namita Singh, parents of the victims say they are losing hope in receiving justice

© AFP via Getty Images

With two years until the tournament, Steve Borthwick’s side are entering a new phase and carry real optimism into November

© Getty

She’s played a Jane Austen hero, a swashbuckling aristocrat, and a wartime cryptanalyst. Now, the beloved actor steps into her most unexpected role yet, as a children’s author. She talks to Jessie Thompson about her daughter’s teething problems, getting equal pay, and that famous ‘Vanity Fair’ photoshoot

© Getty

The Passat estate returns as a plug-in hybrid that’s spacious, steady and reassuringly understated – a car for grown-ups, finds Sean O’Grady

© Sean O’Grady

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© PA Wire

© PA Wire

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© AP2003

© Copyright 1959 AP. All rights reserved.

The model hosts her annual star-studded Halloween bash in New York City

© CJ Rivera/Invision/AP

© The Canadian Press

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Reports of the federal agents wearing horror masks on Halloween were shared by local outlets in Los Angeles

© REUTERS

Officials say the next playoff format will better highlight season-long success and help build future stars.

© James Gilbert

Phelps says the sport’s value continues to climb even as 23XI Racing’s federal antitrust suit exposes internal conversations and financial figures.

© Jared C. Tilton

LaGuardia is one of several airports in the country facing delays due to staffing shortages amid the government shutdown

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

The White House’s East Wing was demolished last week to make room for President Donald Trump’s $300 million ballroom

© Comedy Central

Fox News host Will Cain grilled retired astronaut Eileen Collins on various conspiracies on the moon landing in an interview Friday

© NASA Archive

© Samuel Corum/Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Trump’s feud with CBS lasted for months and set the stage for a controversial merger that sees the network under control of a top ally’s son

© AP

© Jordan Strauss/Invision/AP, File

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© AFP via Getty Images

© Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Donald Trump / Truth Social

The Republican congresswoman was ‘very irate’ and ‘talking loudly using profanity,’ the police report says

-speaks-as-the-House-Committee-on-Oversight-and-Gov.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty

The official stated that the remains were initially handed over to the Red Cross by Hamas in Gaza

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Ben Angel

© Francesco Carta fotografo | Getty Images

Hold your breath.

Hold your breath.

© Santiago Felipe/Getty Images

Jackie O’s grandson slammed the decision as ‘disgusting, desperate and dangerous’

© Getty Images

In the meetings, which occur around 10 a.m., the White House homeland security adviser reportedly grills officials on visa and immigration issues

© Getty

© AP Photo/Peter Dejong

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© CHRIS DELMAS/AFP via Getty Images)

Combs' lawyers had asked a judge earlier this month to “strongly recommend” transferring him to a low-security male prison

© AP

© Copyright 2024 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The jet performed ‘exactly as planned’ during its test flight over California

© Lockheed Martin Aeronautics

© Action Images via Reuters

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Peter Byrne/PA

Palace are set to play three games in five days after reaching the last eight and want to move the Carabao Cup tie

© AP Photo/Bebeto Matthews, File

Watch as a pet monkey in a diaper escapes its owners and runs around a Texas Halloween shop.

© Plano Police Department/TMX

Sinner defeated Ben Shelton 6-3 6-3 to set up a semi-final with defending champion Alexander Zverev on Saturday

© Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© PA Wire

© PA Wire

Slot says his employers agree with his analysis that injuries are a major reason for Liverpool losing six of their last seven games

© Getty

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The striker scored a perfect hat-trick after half-time to end Coventry’s run of six wins in a row and their unbeaten start

© Getty Images

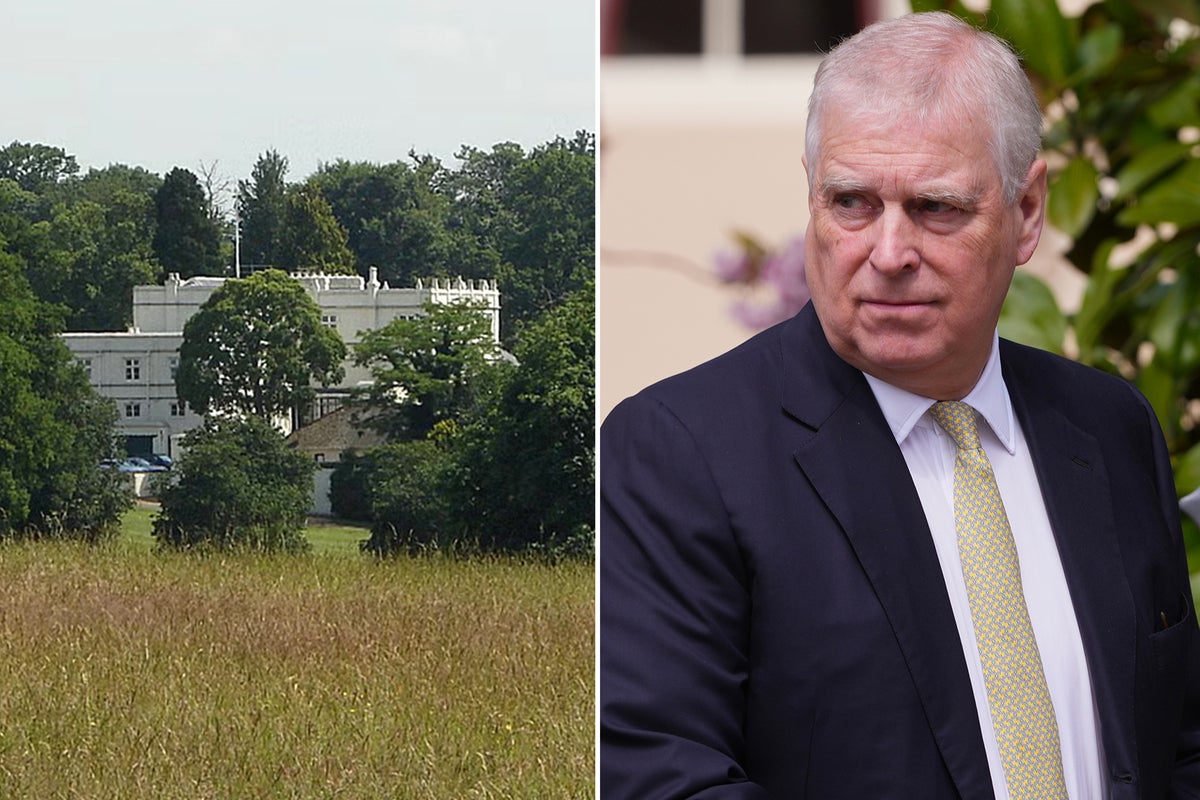

Decision to strip Andrew Mountbatten Windsor of his titles was influenced by Queen’s concerns, reports say

© POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Von has previously hosted Trump on his popular podcast

© Getty Images

Earps’ autobiography All In has been serialised ahead of its release, lifting the lid on her decision to retire ahead of the Euros this year

© The FA via Getty Images

The judge determined that the directive requiring proof of citizenship represents an unconstitutional breach of the separation of powers

© REUTERS

© Copyright 2022 Associated Press. All rights reserved

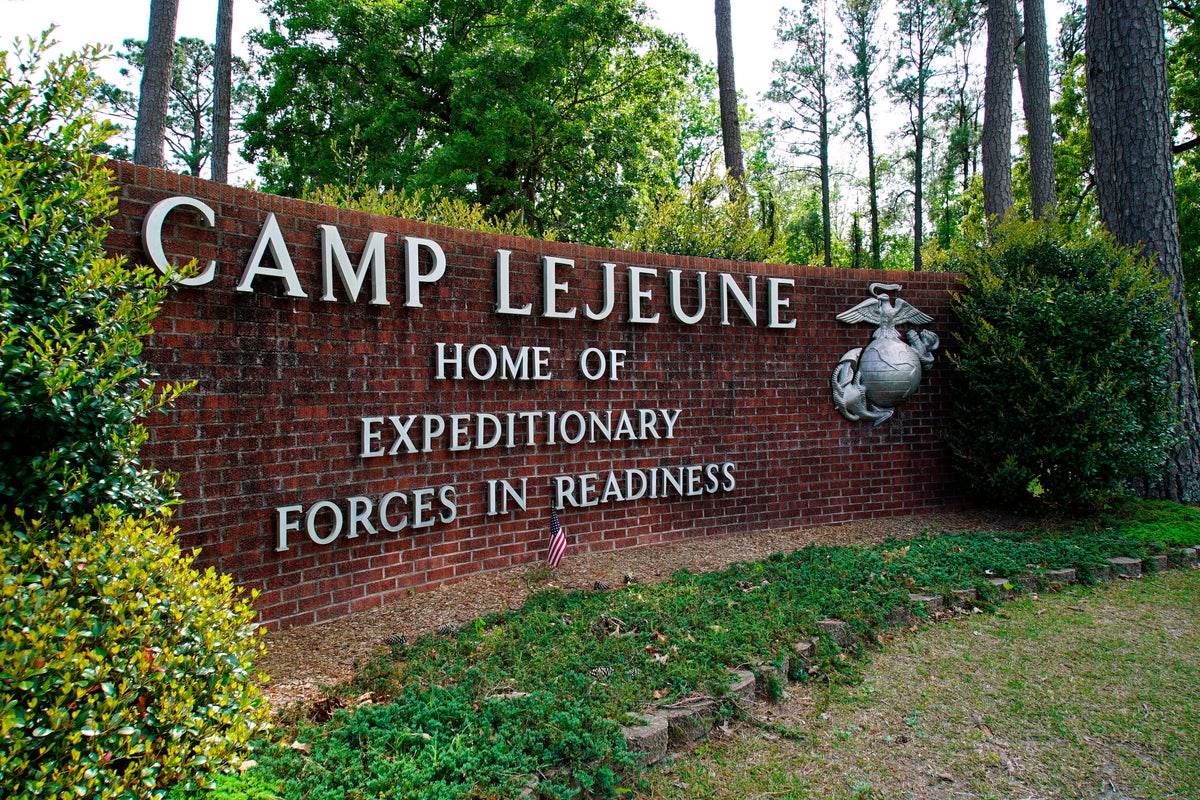

The incident began about 90 miles outside of Raleigh, North Carolina

© Getty Images

Her brother, Sky Roberts, praised the king for ‘setting a precedent to the rest of the world’

© Transworld

© Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Evan Agostini/Getty Images

© PA Media

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File

The winner said his wife didn’t believe his win until their son confirmed it on the Ohio Lottery app

© Getty Images

Strictly Come Dancing’s Karen Hauer has spoken out on the “harsh” criticism she received from the judges over her choreography.

© BBC

Jadynn Hamilton, 17, was arrested and charged Wednesday night, following the death of 73-year-old Ollie Hamilton from the Athens community

© Monroe County Sheriff's Office

© Photo by Eric Lee/Getty Images

People who drink alcohol are more likely to believe it has no effect on cancer risk

© Getty Images for NYCWFF

© AFP via Getty Images

The former undisputed champion has long been a proponent of a significant rule change in women’s boxing

© Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

A recent study provides evidence that while a diet high in fat and sugar is associated with memory impairment, habitual caffeine consumption is unlikely to offer protection against these negative effects. These findings, which come from two related experiments, help clarify the complex interplay between diet, stimulants, and cognitive health in humans. The findings were published in Physiology & Behavior.

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the connection between nutrition and brain function. A growing body of scientific work, primarily from animal studies, has shown that diets rich in fat and sugar can impair memory, particularly functions related to the hippocampus, a brain region vital for learning and recall.

Human studies have started to align with these findings, linking high-fat, high-sugar consumption with poorer performance on memory tasks and with more self-reported memory failures. Given these associations, scientists are searching for potential protective factors that might lessen the cognitive impact of a poor diet.

Caffeine is one of the most widely consumed psychoactive substances in the world, and its effects on cognition have been studied extensively. While caffeine is known to improve alertness and reaction time, its impact on memory has been less clear. Some research in animal models has suggested that caffeine could have neuroprotective properties, potentially guarding against the memory deficits induced by a high-fat, high-sugar diet. These animal studies hinted that caffeine might work by reducing inflammation or through other brain-protective mechanisms. However, this potential protective effect had not been thoroughly investigated in human populations, a gap this new research aimed to address.

To explore this relationship, the researchers conducted two experiments. In the first experiment, they recruited 1,000 healthy volunteers between the ages of 18 and 45. Participants completed a series of online questionnaires designed to assess their dietary habits, memory, and caffeine intake. Their consumption of fat and sugar was measured using the Dietary Fat and free Sugar questionnaire, which asks about the frequency of eating various foods over the past year.

To gauge memory, participants filled out the Everyday Memory Questionnaire, a self-report measure where they rated how often they experience common memory lapses, such as forgetting names or misplacing items. Finally, they reported their daily caffeine consumption from various sources like coffee, tea, and soda.

The results from this first experiment confirmed a link between diet and self-perceived memory. Individuals who reported eating a diet higher in fat and sugar also reported experiencing more frequent everyday memory failures. The researchers then analyzed whether caffeine consumption altered this relationship. The analysis suggested a potential, though not statistically strong, moderating effect.

When the researchers specifically isolated the fat component of the diet, they found that caffeine consumption did appear to weaken the association between high fat intake and self-reported memory problems. At low levels of caffeine intake, a high-fat diet was strongly linked to memory complaints, but this link was not present for those with high caffeine intake. This provided preliminary evidence that caffeine might offer some benefit.

The second experiment was designed to build upon the initial findings with a more robust assessment of memory. This study involved 699 healthy volunteers, again aged 18 to 45, who completed the same questionnaires on diet, memory failures, and caffeine use. The key addition in this experiment was an objective measure of memory called the Verbal Paired Associates task. In this task, participants were shown pairs of words and were later asked to recall the second word of a pair when shown the first. This test provides a direct measure of episodic memory, which is the ability to recall specific events and experiences.

The findings from the second experiment once again showed a clear association between diet and memory. A higher intake of fat and sugar was linked to more self-reported memory failures, replicating the results of the first experiment. The diet was also associated with poorer performance on the objective Verbal Paired Associates task, providing stronger evidence that a high-fat, high-sugar diet is connected to actual memory impairment, not just the perception of it.

When the researchers examined the role of caffeine in this second experiment, the results were different from the first. This time, caffeine consumption did not moderate the relationship between a high-fat, high-sugar diet and either of the memory measures. In other words, individuals who consumed high amounts of caffeine were just as likely to show diet-related memory deficits as those who consumed little or no caffeine.

This lack of a protective effect was consistent for both self-reported memory failures and performance on the objective word-pair task. The findings from this more comprehensive experiment did not support the initial suggestion that caffeine could shield memory from the effects of a poor diet.

The researchers acknowledge certain limitations in their study. The data on diet and caffeine consumption were based on self-reports, which can be subject to recall errors. The participants were also relatively young and generally healthy, and the effects of diet on memory might be more pronounced in older populations or those with pre-existing health conditions. Since the study was conducted online, it was not possible to control for participants’ caffeine intake right before they completed the memory tasks, which could have influenced performance.

For future research, the scientists suggest using more objective methods to track dietary intake. They also recommend studying different populations, such as older adults or individuals with obesity, where the links between diet, caffeine, and memory may be clearer. Including a wider array of cognitive tests could also help determine if caffeine has protective effects on other brain functions beyond episodic memory, such as attention or executive function. Despite the lack of a protective effect found here, the study adds to our understanding of how lifestyle factors interact to influence cognitive health.

The study, “Does habitual caffeine consumption moderate the association between a high fat and sugar diet and self-reported and episodic memory impairment in humans?,” was authored by Tatum Sevenoaks and Martin Yeomans.

Here's what you need to know.

Here's what you need to know.

This is the first phase of a planned two-phase program to help officials communicate in real time

© Getty Images

New York City’s JFK Airport was under a ground stop for several hours on Friday

© AFP via Getty Images

A new study found that switching back-and-forth is the worst option for our health

© Getty/iStock

Detainees are packed into holding rooms ‘like animals’ without adequate food, water and medication, plaintiffs allege

© AFP via Getty Images

© Kirsty Wigglesworth

When asked about Bari Weiss considering Dana Perino to lead CBS Evening News, one senior CBS News staffer responded to The Independent with a face-palm emoji.

© Copyright 2021 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The new bathroom is in keeping with the president’s gilded makeover of the White House

© Donald Trump / Truth Social

With the ‘Mother Road’ celebrating its 100th birthday next year, Laura French goes back to where it all began and explores the birthplace of America’s most famous highway

© Laura French /The Independent

Roberto Vidanos was crossing the street in Pleasantville when he was hit hard by a driver and sustained severe injuries

© Pleasantville Fire Department

Jeff Hersh had had to put his belongings in storage when a burst water pipe in his neighbor’s unit flooded his apartment

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

A White House official said "the tide is turning" on prioritizing climate change

© Photo by Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

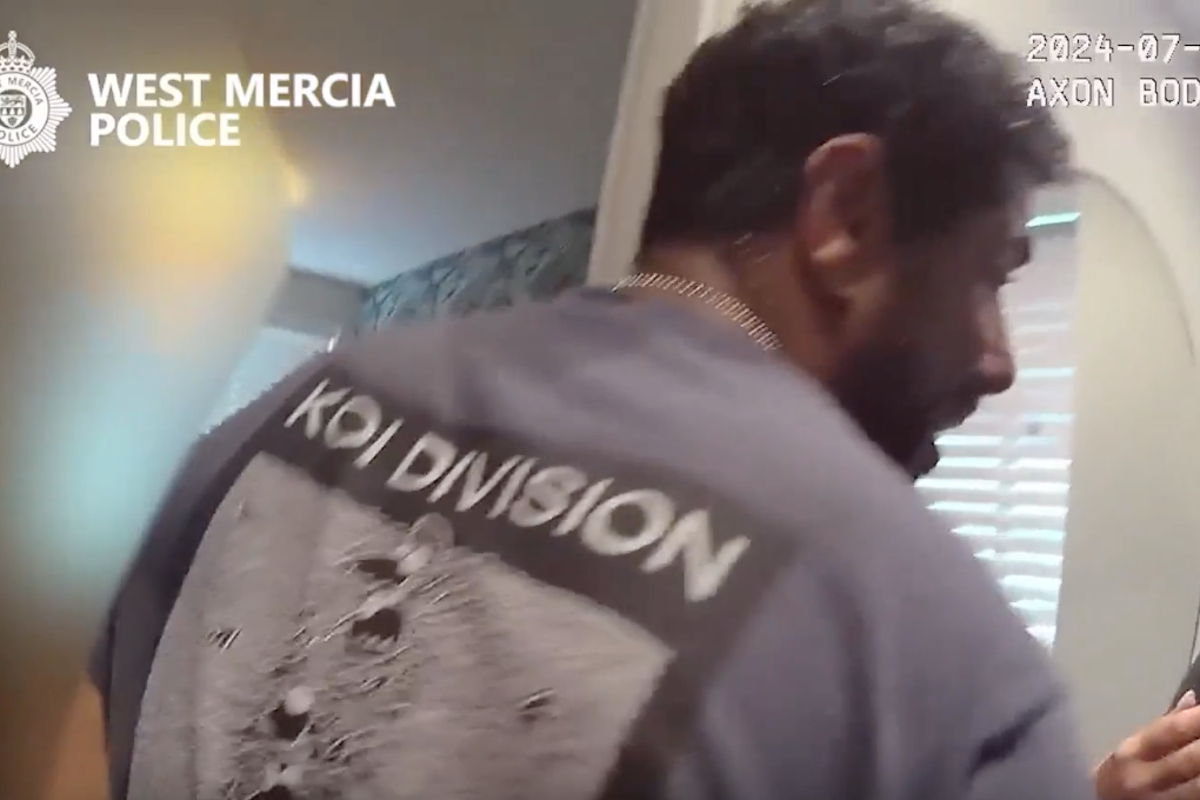

Police have released the arrest footage of Mohamad Samak, an Egyptian former international hockey player, who brutally stabbed his wife to death last year.

© West Mercia Police

Crawford has hinted at moving down in weight to target a world title in a sixth separate division

© Getty

Roughly 16 percent of the 861 children whose mothers had Covid during their pregnancy received a neurodevelopmental diagnosis

© AFP via Getty Images

Republicans have resisted the temptation to eliminate the filibuster so far, writes Eric Garcia. But Trump has a way of beating them into submission

© AP

Kelly Osbourne’s son made a sweet Halloween tribute to grandfather Ozzy by recreating one of his most infamous moments.

© PA/Kelly Osbourne

Trump announced he was adding the West African country to the State Department’s watch list

© AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta

Earlier this year, Sarah Ferguson claimed that the late Queen communicated to her through the dogs’ barking

© REUTERS/Peter Nicholls/Pool

A high-speed train in the Netherlands smashed into a lorry after it reversed over a level crossing, leaving its five occupants injured.

© ProRail

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Tours were suspended in August to make way for construction of the planned ballroom

© Reuters

Jaysley Beck’s family blame attack by Michael Webber and handling of assault by army for 19-year-old’s death

© PA

© PA Wire

Majority of Republicans have strongly resisted calls to eliminate the legislative filibuster

© AFP via Getty Images

Buatsi is back in action this weekend, facing Zach Parker as he aims to bounce back from his loss to Callum Smith

© Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

A U.S. official said the military had provided a range of options, including strikes against military facilities inside Venezuela

© Samuel Corum/Getty Images

© Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Federal judges say USDA must tap into billions of dollars in emergency funds to keep critical food assistance afloat

© REUTERS

Andrew has faced accusations of sexual assault from women who were trafficked by the late financier

© AFP/Getty

Many fans are still desperate to see Joshua and Fury clash in 2026

© Getty Images

Buatsi suffered his first professional loss earlier this year and has made significant changes to ensure it does not happen again

© PA Wire

Eilish is donating $11.5 million from her world tour to charity

© Getty Images for WSJ. Magazine I

Tens of thousands of seats have remained empty during theater, orchestra, and dance performances at the institution

© Getty Images

From favorite son to tabloid fodder, Prince Andrew this week was stripped of his remaining titles and evicted from his royal residence after weeks of pressure to act over his relationship with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

© Copyright 2010 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Ditch the cable, and zip through the cleaning with these dust-busting machines

© Joanne Lewsley/The Independent

© AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein

The crash left wooden crates marked ‘live monkeys’ in the tall grass on the side of the road

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

CEOs warn that continued shutdown will lead to more delays and flight cancellations – but Democrats insist that dropping their objections would jeopardize the health insurance of millions of Americans

© REUTERS

Most school districts in Wisconsin had already restricted cellphone use in the classroom

© PA Wire

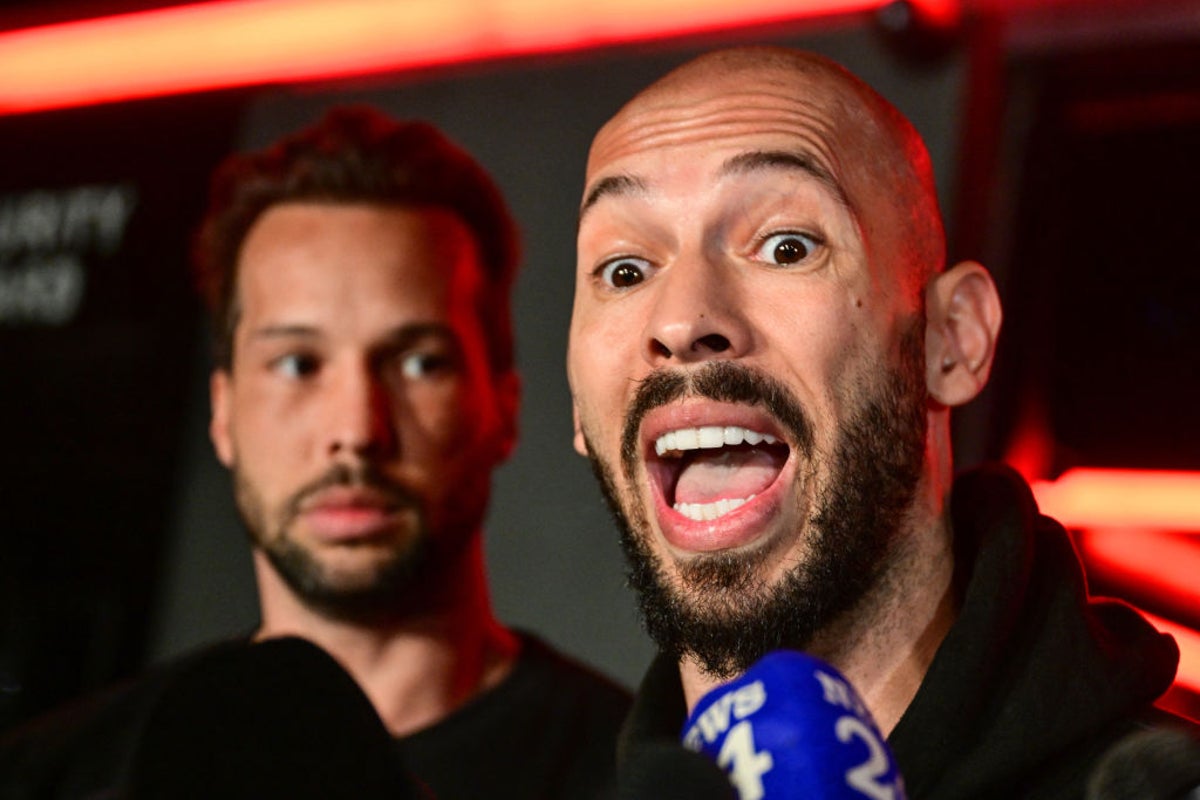

Comment: The self-confessed misogynist, who has faced numerous allegations of rape and human trafficking, should not be given this kind of platform

© AFP via Getty Images

More than 40 million Americans who rely on SNAP, also known as food stamps, are at risk of losing benefits over the weekend

© Getty Images

More parents are asking with autistic children are asking to prescribe leucovorin despite a lack of data about its benefits

© Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

Around 1,120 staff across the chain will transfer to the new ownership

© PA Media

While in the Japanese capital, Tamara Davison checks into Hoshinoya Tokyo, a haven in the middle of the city where guests seeking quiet luxury can switch off

© HOSHINOYA Tokyo

© REUTERS/Leah Millis

Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao could fight each other again next year, 11 years after their initial clash

© AFP via Getty Images

The Man Who Pays His Way: The builders have reached the finish line for Cairo’s Grand Egyptian Museum, and now the race to the past begins

© Charlotte Hindle

© Copyright 2024 The Associated Press All rights reserved

The elderly biker dipped into the bottles of red in his shopping bag, after he had an accident in the Cévennes region of France

Two incidents of threatened political violence target Connecticut officials in same week

© Waterbury Police

This week on Streamline, we dive into The Celebrity Traitors – the ultimate watercooler show where Britain’s best-loved stars lie, bluff and backstab their way to victory. From Jonathan Ross being a style icon that rivals Claudia Winkleman, to Alan Carr’s theatrics, it’s the no-so guilty pleasure that’s got us all hooked.

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© The Independent, BBC

The former model won the first-ever season of the reality show in 2003

© Getty Images

© PA Archive

Young indigenous activist Taily Terena, speaking to Nick Ferris as fires burn through the wetland environment where her people live, criticises the Brazilian government pushing for oil extraction at the same time as hosting world’s most important climate conference

© Getty Images/iStockphoto

It is hoped ‘Forest City 1’ will see 400,000 homes built across 45,000 acres of land, alongside 12,000 acres of woodland in Suffolk

© Forest City

US lawyer Gloria Allred, who represented several of Epstein’s victims, backed moves to change the names

© PA/PA Wire

Laura Harvey told a podcast that she has changed formations this season following advice from the AI chatbot

© Getty Images

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© mogul

© Getty Images

© urbazon | Getty Images

© Andriy Onufriyenko | Getty Images

© Natalya Kosarevich | Getty Images

A team of researchers in Brazil has engineered an inexpensive, disposable sensor that can detect a key protein linked to mental health conditions using a drop of saliva. Published in the journal ACS Polymers Au, the device could one day offer a rapid, non-invasive tool to help in the diagnosis and monitoring of disorders like depression and schizophrenia. The results are available in under an hour, offering a significant departure from current lab-based methods.

Diagnosing and managing psychiatric disorders currently relies heavily on clinical interviews and patient-reported symptoms, which can be subjective. Scientists have been searching for objective biological markers, and a protein called brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF, has emerged as a promising candidate. Lower-than-normal levels of BDNF, which supports the health and growth of neurons, have been consistently associated with conditions like major depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Existing methods for measuring BDNF typically involve blood draws and rely on complex, time-consuming laboratory procedures like the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. These techniques are often expensive and require specialized equipment and personnel, making them impractical for routine clinical use or for monitoring patient progress outside of a dedicated lab. The researchers sought to develop a fast, affordable, and non-invasive alternative that could be used at the point of care, motivated by the global increase in mental health conditions.

The foundation of the device is a small, flexible strip of polyester, similar to a piece of plastic film. Using a screen-printing technique, the scientists printed three electrodes onto this strip using carbon- and silver-based inks. This fabrication method is common in electronics and allows for inexpensive, mass production of the sensor strips.

To make the sensor specific to BDNF, the team modified the surface of the main working electrode in a multi-step process. First, they coated it with a layer of microscopic carbon spheres, which are synthesized from a simple glucose solution. This creates a large, textured surface area that is ideal for anchoring other molecules and enhances the sensor’s electrical sensitivity.

Next, they added a sequence of chemical layers that act as a sticky foundation for the biological components. Onto this foundation, they attached specialized proteins called antibodies. These anti-BDNF antibodies are engineered to recognize and bind exclusively to the BDNF protein, much like a key fits into a specific lock. A final chemical layer was added to block any remaining empty spots on the surface, which prevents other molecules in saliva from interfering with the measurement.

When a drop of saliva is applied to the sensor, any BDNF protein present is captured by the antibodies on the electrode. This binding event physically alters the electrode’s surface, creating a minute barrier that impedes the flow of electrons. The device then measures this change by sending a small electrical signal through the electrode and recording its resistance to that signal.

A greater amount of captured BDNF creates a larger barrier, resulting in a higher resistance, which can be precisely quantified. The entire process, from sample application to result, can be completed in about 35 minutes. The data is captured by a portable analyzer that can communicate wirelessly with a device like a smartphone, allowing for real-time analysis.

The research team demonstrated that their biosensor was remarkably sensitive. It could reliably detect BDNF across a vast concentration range, from incredibly minute amounts (as low as 10⁻²⁰ grams per milliliter) up to levels typically seen in healthy individuals.

This wide detection range is significant because it means the device could potentially identify the very low BDNF levels that may signal a disorder. It could also track the increase in BDNF levels as a patient responds positively to treatment, such as antidepressants, offering an objective measure of therapeutic success.

The sensor also proved to be highly selective. When tested against a variety of other substances commonly found in saliva, including glucose, uric acid, paracetamol, and even the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the device did not produce a false signal. It responded specifically to BDNF, confirming the effectiveness of its design.

Furthermore, tests using human saliva samples that were supplemented with known quantities of the protein showed that the sensor could accurately measure BDNF levels even within this complex biological fluid. The researchers estimated the cost of the materials for a single disposable strip to be around $2.19, positioning it as a potentially accessible diagnostic tool.

The current study was a proof-of-concept and has certain limitations. The experiments were conducted with a limited number of saliva samples from a single volunteer, which were then modified in the lab to contain varying concentrations of the target protein.

The next essential step will be to test the biosensor with a large and diverse group of patients diagnosed with various psychiatric conditions to validate its accuracy and reliability in a real-world clinical setting. Such studies would be needed to establish clear thresholds for what constitutes healthy versus potentially pathological BDNF levels in saliva. The researchers also plan to secure a patent for their technology and refine the device for potential commercial production. Future work could also explore integrating sensors for other biomarkers onto the same strip, allowing for a more comprehensive health assessment from a single saliva sample.

The study, “Low-Cost, Disposable Biosensor for Detection of the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Biomarker in Noninvasively Collected Saliva toward Diagnosis of Mental Disorders,” was authored by Nathalia O. Gomes, Marcelo L. Calegaro, Luiz Henrique C. Mattoso, Sergio A. S. Machado, Osvaldo N. Oliveira Jr., and Paulo A. Raymundo-Pereira.

Researchers have developed a new method for training artificial intelligence that dramatically improves its speed and energy efficiency by mimicking the structured wiring of the human brain. The approach, detailed in the journal Neurocomputing, creates AI models that can match or even exceed the accuracy of conventional networks while using a small fraction of the computational resources.

The study was motivated by a growing challenge in the field of artificial intelligence: sustainability. Modern AI systems, such as the large language models that power generative AI, have become enormous. They are built with billions of connections, and training them can require vast amounts of electricity and cost tens of millions of dollars. As these models continue to expand, their financial and environmental costs are becoming a significant concern.

“Training many of today’s popular large AI models can consume over a million kilowatt-hours of electricity, which is equivalent to the annual use of more than a hundred US homes, and cost tens of millions of dollars,” said Roman Bauer, a senior lecturer at the University of Surrey and a supervisor on the project. “That simply isn’t sustainable at the rate AI continues to grow. Our work shows that intelligent systems can be built far more efficiently, cutting energy demands without sacrificing performance.”

To find a more efficient design, the research team looked to the human brain. While many artificial neural networks are “dense,” meaning every neuron in one layer is connected to every neuron in the next, the brain operates differently. Its connectivity is highly sparse and structured. For instance, in the visual system, neurons in the retina form localized and orderly connections to process information, creating what are known as topographical maps. This design is exceptionally efficient, avoiding the need for redundant wiring. The brain also refines its connections during development, pruning away unnecessary pathways to optimize its structure.

Inspired by these biological principles, the researchers developed a new framework called Topographical Sparse Mapping, or TSM. Instead of building a dense network, TSM configures the input layer of an artificial neural network with a sparse, structured pattern from the very beginning. Each input feature, such as a pixel in an image, is connected to only one neuron in the following layer in an organized, sequential manner. This method immediately reduces the number of connections, known as parameters, which the model must manage.

The team then developed an enhanced version of the framework, named Enhanced Topographical Sparse Mapping, or ETSM. This version introduces a second brain-inspired process. After the network trains for a short period, it undergoes a dynamic pruning stage. During this phase, the model identifies and removes the least important connections throughout its layers, based on their magnitude. This process is analogous to the synaptic pruning that occurs in the brain as it learns and matures, resulting in an even leaner and more refined network.

To evaluate their approach, the scientists built and trained a type of network known as a multilayer perceptron. They tested its ability to perform image classification tasks using several standard benchmark datasets, including MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. This setup allowed for a direct comparison of the TSM and ETSM models against both conventional dense networks and other leading techniques designed to create sparse, efficient AI.

The results showed a remarkable balance of efficiency and performance. The ETSM model was able to achieve extreme levels of sparsity, in some cases removing up to 99 percent of the connections found in a standard network. Despite this massive reduction in complexity, the sparse models performed just as well as, and sometimes better than, their dense counterparts. For the more difficult CIFAR-100 dataset, the ETSM model achieved a 14 percent improvement in accuracy over the next best sparse method while using far fewer connections.

“The brain achieves remarkable efficiency through its structure, with each neuron forming connections that are spatially well-organised,” said Mohsen Kamelian Rad, a PhD student at the University of Surrey and the study’s lead author. “When we mirror this topographical design, we can train AI systems that learn faster, use less energy and perform just as accurately. It’s a new way of thinking about neural networks, built on the same biological principles that make natural intelligence so effective.”

The efficiency gains were substantial. Because the network starts with a sparse structure and does not require complex phases of adding back connections, it trains much more quickly. The researchers’ analysis of computational costs revealed that their method consumed less than one percent of the energy and used significantly less memory than a conventional dense model. This combination of speed, low energy use, and high accuracy sets it apart from many existing methods that often trade performance for efficiency.

A key part of the investigation was to confirm the importance of the orderly, topographical wiring. The team compared their models to networks that had a similar number of sparse connections but were arranged randomly. The results demonstrated that the brain-inspired topographical structure consistently produced more stable training and higher accuracy, indicating that the specific pattern of connectivity is a vital component of its success.

The researchers acknowledge that their current framework applies the topographical mapping only to the model’s input layer. A potential direction for future work is to extend this structured design to deeper layers within the network, which could lead to even greater gains in efficiency. The team is also exploring how the approach could be applied to other AI architectures, such as the large models used for natural language processing, where the efficiency improvements could have a profound impact.

The study, “Topographical sparse mapping: A neuro-inspired sparse training framework for deep learning models,” was authored by Mohsen Kamelian Rad, Ferrante Neri, Sotiris Moschoyiannis, and Roman Bauer.

"It's like watching a train slowly derail, one car at a time."

"It's like watching a train slowly derail, one car at a time."

The collaboration with YouTube builders Jeremiah Burton and Zach Jobe turns Hyundai’s family EV into a capable off-roader with style.

© Hyundai

Check out the cool SEMA concept from Hyundai and BigTime.

© Hyundai

Watch as AFM riders avoided disaster when a misplaced Tesla drove straight onto an active track.

© American Federation of Motorcyclists

Read the latest odds and football tips as Arne Slot’s side look for just a second win in seven games when they host Unai Emery’s Villa

© PA Wire

© Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images

Parts of New York City were submerged in flood water after the Big Apple was hit by record rainfall on Thursday (30 October).

© X

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Watch as Prince Harry is left dumbfounded when asked about Taylor Swift and Charli XCX’s alleged feud.

© Hasan Minhaj

The outbreak has been detected in six states with patients being hospitalized from Illinois to Hawaii

© Getty/iStock

Itauma will have to wait to face the WBA ‘Regular’ champion despite his mandatory challenger status

© Zac Goodwin/PA

Everything you need to know about the best early payout betting sites, from their promotional offers to various pros and cons

© The Independent

The Rob Dyrdek-created series premiered in 2011

© Getty

Your official rundown of the best beauty advents, from Cult Beauty to Selfridges

© The Independent

Lawson said he ‘could have killed’ the two marshals that crossed the track ahead of him in Mexico

© Getty Images

The TV host revealed his father’s prostate cancer diagnosis in July

© ryanseacrest / Instagram

Some 10 million people subscribe to YouTube TV

© AFP via Getty Images

The star of ‘Baby Driver’, ‘The Iron Claw’ and ‘Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again’ now plays a woman fleeing constant surveillance in the thriller ‘Relay’. She talks to Adam White about losing her privacy in the public eye, the time she boasted about her lineage to impress Edgar Wright, and why she has no regrets about playing Pamela Anderson

© Ben Trivett/Shutterstock

Federal aviation workers missed their first paycheck this week as the government shutdown steers toward the longest-ever in U.S. history.

© Reuters

Lee Comley, of Leigh Park, Havant, was arrested on July 1 after a group that calls itself the Child Online Safety Team live-streamed their confrontation with him before police arrived.

© Hampshire Police/PA Wire

The Nio ET9 has been developed to give it a true magic carpet ride. Electric vehicles editor Steve Fowler tested it on Britain’s broken roads to find out if it lives up to the claims

© Steve Fowler

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The future is likely to look very different for Andrew after his spectacular fall from grace

Mayer currently holds belts at two separate weights – and if she gets her way, she will retain them going forward as she pursues undisputed status

© Getty Images

A hint: It’s not spiders

© Getty Images

Klewin says that her mother was given seven drinks over six hours, despite being visibly intoxicated

© AFP via Getty Images

From budget bubbles to organic fizz, these are the proseccos to stock up on

© Lily Thomas/The Independent

The expanded Champions League and exclusive weekends for the FA Cup has led to the Premier League scrapping its traditional feast of Boxing Day football

© Peter Byrne/PA Wire

New ‘super ships’ are coming to the luxury brand’s fleet

© Uniworld

Editorial: Keir Starmer has said his chancellor will face no further action for ‘inadvertently’ failing to obtain a licence to rent out her home, and then misleading him about it. But she has fallen far below the standards that she set for her political opponents

© PA

From a daytime techno underground rave in Ukraine and pumpkin carving in Romania to a bash hosted by the U.S. President and his wife at the White House, the U.S. Halloween tradition is celebrated around the world.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Watch as Donald Trump puts candy on a child’s head during a Halloween event at the White House.

© AP

The thieves fled with eight crown jewel pieces within minutes

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The Russian military claims that the Burevestnik missile flew 8,700 miles at low altitude over 15 hours

© POOL/AFP via Getty Images

‘If you are here driving on our streets illegally and our highways, you are endangering our citizens, and your days are numbered,’ the Homeland Security Secretary warned

© AP

© Jay McGowan/Cornell Lab of Ornithology via AP

© Arsenal FC via Getty Images

King’s AI criticism came hours after a report indicated she could be leaving ‘CBS Mornings’

© CBS

Many people in other parts of the U.S. also have reported making special treks to the region in hopes of seeing it

© Jay McGowan/Cornell Lab of Ornithology via AP

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© The Independent/Getty Images/Pixabay

© The Independent/Getty Images/Pixabay

Whiteman, who joined Spurs’s academy at the age of 10, also hosts a radio show

© Getty Images

Neil deGrasse Tyson said the “earth is flat” in a terrifying AI deepfake, which he shared to his followers to warn of the dangers of the new technology.

© StarTalk

Shaine March was aged 21 when he fatally stabbed 17-year-old Andre Drummond in the neck at a McDonald’s restaurant in Denmark Hill

© Family Handout/PA Wire

Eliud Kipchoge will complete his mission to feature at every marathon major throughout the five boroughs

© Getty Images for Adidas

Guests can party with top DJs from the channel

© Ambassador Cruise Line

Giant Eagle and Sheetz are finding creative ways to collect pennies as the US Treasury phases out 1-cent coin production

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

‘I don’t need a briefing. Bad guys are dying, I like it,’ Lawrence Jones declared on Friday.

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Fox News

© Getty Images

Haney will return to the ring in an attempt to become a three-weight world champion, when he faces WBO welterweight champion Brian Norman Jr on 22 November

© Getty Images

Horse racing correspondent Jonathan Doidge brings us selected tips for Saturday’s cards at Ascot and Wetherby.

© Getty Images

Experts say reviving the long-dormant testing program could take at least a year and would cost astronomical amounts for each test

© U.S. Energy Department

© Ukrainian Emergency Service

The anchor has been diagnosed with cancer twice

© Getty Images

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Everything you need to know about Premium Bonds

© Getty

The ‘Ted Lasso’ star has stolen the hearts of ‘Traitors’ fans during his time on the all-star spin-off

© BBC

The firing squad is a new addition to South Carolina's execution methods

© AP

Previous years have seen site-wide discounts, including up to 50 per cent off

© The Independent

Some of the sweet beverages have more than your daily allowance of added sugar

© AFP via Getty Images

Billie Eilish told a crowd of the wealthy elite to give away some of their fortunes, as she pledged to donate $11.5 million from her recent world tour.

© WSJ/Reuters

The Trump administration has conducted at least 13 strikes, killing 57 in the Caribbean Sea and eastern Pacific

© Kim Kyung-Hoon/Pool Photo via AP

© PA Wire

© Nick Potts/PA

© Suzanne Plunkett/PA Wire/PA Images

© PA Archive

© BBC Studios/Bad Wolf/James Pardon

© South Carolina Department of Corrections

© Kosamtu | Getty Images

© StackCommerce

© Bloomberg | Getty Images

© Photo by Noah Berger/Getty Images for Amazon Web Services

© Halfpoint Images | Getty Images

© Smash Kitchen

A new study provides evidence that a person’s innate vulnerability to stress-induced sleep problems can intensify how much a racing mind disrupts their sleep over time. While daily stress affects everyone’s sleep to some degree, this trait appears to make some people more susceptible to fragmented sleep. The findings were published in the Journal of Sleep Research.

Scientists have long understood that stress can be detrimental to sleep. One of the primary ways this occurs is through pre-sleep arousal, a state of heightened mental or physical activity just before bedtime. Researchers have also identified a trait known as sleep reactivity, which describes how susceptible a person’s sleep is to disruption from stress. Some individuals have high sleep reactivity, meaning their sleep is easily disturbed by stressors, while others have low reactivity and can sleep soundly even under pressure.

Despite knowing these factors are related, the precise way they interact on a daily basis was not well understood. Most previous studies relied on infrequent, retrospective reports or focused on major life events rather than common, everyday stressors. The research team behind this new study sought to get a more detailed picture. They aimed to understand how sleep reactivity might alter the connection between daily stress, pre-sleep arousal, and objectively measured sleep patterns in a natural setting.

“Sleep reactivity refers to an individual’s tendency to experience heightened sleep disturbances when faced with stress. Those with high sleep reactivity tend to show increased pre-sleep arousal during stressful periods and are at greater risk of developing both acute and chronic insomnia,” explained study authors Ju Lynn Ong and Stijn Massar, who are both research assistant professors at the National University of Singapore Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine.

“However, most prior research on stress, sleep, and sleep reactivity has relied on single, retrospective assessments, which may fail to capture the immediate and dynamic effects of daily stressors on sleep. Another limitation is that previous studies often examined either the cognitive or physiological components of pre-sleep arousal in isolation. Although these two forms of arousal are related, they may differ in their predictive value and underlying mechanisms, highlighting the importance of evaluating both concurrently.”

“To address these gaps, the current study investigated how day-to-day fluctuations in stress relate to sleep among university students over a two-week period and whether pre-sleep cognitive and physiological arousal mediate this relationship—particularly in individuals with high sleep reactivity.”

The research team began by recruiting a large group of full-time university students. They had the students complete a questionnaire called the Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test, which is designed to measure an individual’s sleep reactivity. From this initial pool, the researchers selected two distinct groups for a more intensive two-week study: 30 students with the lowest scores, indicating low sleep reactivity, and 30 students with the highest scores, representing high sleep reactivity.

Over the following 14 days, these 60 participants were monitored using several methods. They wore an actigraphy watch on their wrist, which uses motion sensors to provide objective data on sleep patterns. This device measured their total sleep time, the amount of time it took them to fall asleep, and the time they spent awake after initially drifting off. Participants also wore an ŌURA ring, which recorded their pre-sleep heart rate as an objective indicator of physiological arousal.

Alongside these objective measures, participants completed daily surveys on their personal devices. Each evening before going to bed, they rated their perceived level of stress. Upon waking the next morning, they reported on their pre-sleep arousal from the previous night. These reports distinguished between cognitive arousal, such as having racing thoughts or worries, and somatic arousal, which includes physical symptoms like a pounding heart or muscle tension.

The first part of the analysis examined within-individual changes, which looks at how a person’s sleep on a high-stress day compared to their own personal average. The results showed that on days when participants felt more stressed than usual, they also experienced a greater degree of pre-sleep cognitive arousal. This increase in racing thoughts was, in turn, associated with getting less total sleep and taking longer to fall asleep that night. This pattern was observed in both the high and low sleep reactivity groups.

This finding suggests that experiencing a more stressful day than usual is likely to disrupt anyone’s sleep to some extent, regardless of their underlying reactivity. It appears to be a common human response for stress to activate the mind at bedtime, making sleep more difficult. The trait of sleep reactivity did not seem to alter this immediate, day-to-day effect.

“We were surprised to find that at the daily level, all participants did in fact exhibit a link between higher perceived stress and poorer sleep the following night, regardless of their level of sleep reactivity,” Ong and Massar told PsyPost. “This pattern may reflect sleep disturbances as a natural—and potentially adaptive—response to stress.”

The researchers then turned to between-individual differences, comparing the overall patterns of people in the high-reactivity group to those in the low-reactivity group across the entire two-week period. In this analysis, a key distinction became clear. Sleep reactivity did in fact play a moderating role, amplifying the negative effects of stress and arousal.

Individuals with high sleep reactivity showed a much stronger connection between their average stress levels, their average pre-sleep cognitive arousal, and their sleep quality. For these highly reactive individuals, having higher average levels of cognitive arousal was specifically linked to spending more time awake after initially falling asleep. In other words, their predisposition to stress-related sleep disturbance made their racing thoughts more disruptive to maintaining sleep throughout the night.

The researchers also tested whether physiological arousal played a similar role in connecting stress to poor sleep. They examined both the participants’ self-reports of physical tension and their objectively measured pre-sleep heart rate. Neither of these measures of physiological arousal appeared to be a significant middleman in the relationship between stress and sleep, for either group. The link between stress and sleep disruption in this study seemed to operate primarily through mental, not physical, arousal.

“On a day-to-day level, both groups exhibited heightened pre-sleep cognitive arousal and greater sleep disturbances in response to elevated daily stress,” the researchers explained. “However, when considering the study period as a whole, individuals with high sleep reactivity consistently reported higher average levels of stress and pre-sleep cognitive arousal, which in turn contributed to more severe sleep disruptions compared to low-reactive sleepers. Notably, these stress → pre-sleep arousal → sleep associations emerged only for cognitive arousal, not for somatic arousal—whether assessed through self-reports or objectively measured via pre-sleep heart rate.”

The researchers acknowledged some limitations of their work. The study sample consisted of young university students who were predominantly female and of Chinese descent, so the results may not be generalizable to other demographic groups or age ranges. Additionally, the study excluded individuals with diagnosed sleep disorders, meaning the findings might differ in a clinical population. The timing of the arousal survey, completed in the morning, also means it was a retrospective report that could have been influenced by the night’s sleep. It is also important to consider the practical size of these effects.

While statistically significant, the changes were modest: a day with stress levels 10 points higher than usual was linked to about 2.5 minutes less sleep, and the amplified effect in high-reactivity individuals amounted to about 1.2 additional minutes of wakefulness during the night for every 10-point increase in average stress.

Future research could build on these findings by exploring the same dynamics in more diverse populations. The study also highlights pre-sleep cognitive arousal as a potential target for intervention, especially for those with high sleep reactivity. Investigating whether therapies like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia can reduce this mental activation could offer a path to preventing temporary, stress-induced sleep problems from developing into chronic conditions.

The study, “Sleep Reactivity Amplifies the Impact of Pre-Sleep Cognitive Arousal on Sleep Disturbances,” was authored by Noof Abdullah Saad Shaif, Julian Lim, Anthony N. Reffi, Michael W. L. Chee, Stijn A. A. Massar, and Ju Lynn Ong.

A new study reveals the human brain’s remarkable ability to maintain communication between its two hemispheres even when the primary connection is almost entirely severed. Researchers discovered that a tiny fraction of remaining nerve fibers is sufficient to sustain near-normal levels of integrated brain function, a finding published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. This observation challenges long-held ideas about how the brain is wired and suggests an immense potential for reorganization after injury.

The brain’s left and right hemispheres are linked by the corpus callosum, a massive bundle of about 200 million nerve fibers that acts as a superhighway for information. For decades, scientists have operated under the assumption that this structure has a map-like organization, where specific fibers connect corresponding regions in each hemisphere to perform specialized tasks. Based on this model, damage to a part of the corpus callosum should result in specific, predictable communication breakdowns between the brain halves.

To test this idea, researchers turned to a unique group of individuals known as split-brain patients. These patients have undergone a rare surgical procedure called a callosotomy, where the corpus callosum is intentionally cut to treat severe, otherwise untreatable epilepsy. This procedure provides a distinct opportunity to observe how the brain functions when its main inter-hemispheric pathway is disrupted. Because the surgery is no longer common, data from adult patients using modern neuroimaging techniques has been scarce, leaving a gap in understanding how this profound structural change affects the brain’s functional networks.

The international research team studied six adult patients who had undergone the callosotomy procedure. Four of the patients had a complete transection, meaning the entire corpus callosum was severed. Two other patients had partial transections. One had about 62 percent of the structure intact, while another, patient BT, had approximately 90 percent of his corpus callosum removed, leaving only a small segment of fibers, about one centimeter wide, at the very back of the structure.

To assess the functional consequences, the researchers first performed simple bedside behavioral tests. The four patients with complete cuts exhibited classic “disconnection syndromes,” where one hemisphere appeared unable to share information with the other. For example, they could not verbally name an object placed in their left hand without looking at it, because the sensation from the left hand is processed by the right hemisphere, while language is typically managed by the left. The two hemispheres were acting independently.

In contrast, both patients with partial cuts showed no signs of disconnection. Patient BT, despite having only a tiny bridge of fibers remaining, could perform these tasks successfully, indicating robust communication was occurring between his hemispheres.

To look directly at brain activity, the team used resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. This technique measures changes in blood flow throughout the brain, allowing scientists to identify which regions are active and working together. When two regions show synchronized activity over time, they are considered to be functionally connected. The researchers compared the brain activity of the six patients to a benchmark dataset from 100 healthy adults.

In the four patients with a completely severed corpus callosum, the researchers saw a dramatic reduction in functional connectivity between the two hemispheres. The brain’s large-scale networks, which normally span both sides of the brain, appeared highly “lateralized,” meaning their activity was largely confined to either the left or the right hemisphere. It was as if each side of the brain was operating in its own bubble, with very little coordination between them.

The findings from the two partially separated patients were strikingly different. Their patterns of interhemispheric functional connectivity looked nearly identical to those of the healthy control group. Even in patient BT, the small remnant of posterior fibers was enough to support widespread, brain-wide functional integration. His brain networks for attention, sensory processing, and higher-order thought all showed normal levels of bilateral coordination. This result directly contradicts the classical model, which would have predicted that only the brain regions directly connected by those few remaining fibers, likely related to vision, would show preserved communication.

The researchers also analyzed the brain’s dynamic activity, looking at how moment-to-moment fluctuations are synchronized across the brain. In healthy individuals, the overall rhythm of activity in the left hemisphere is tightly coupled with the rhythm in the right hemisphere. In the patients with complete cuts, these rhythms were desynchronized, as if each hemisphere was marching to the beat of its own drum.

Yet again, the two patients with partial cuts showed a strong, healthy synchronization between their hemispheres, suggesting the small bundle of fibers was sufficient to coordinate the brain’s global dynamics. Patient BT’s brain had apparently reorganized its functional networks over the six years since his surgery to make optimal use of this minimal structural connection.

The study is limited by its small number of participants, a common challenge in research involving rare medical conditions. Because the callosotomy procedure is seldom performed today, finding adult patients for study is difficult. While the differences observed between the groups were pronounced, larger studies would be needed to fully characterize the range of outcomes and the ways in which brains reorganize over different timescales following surgery.

Future research could focus on tracking patients over many years to map the process of neural reorganization in greater detail. Such work may help uncover the principles that govern the brain’s plasticity and its ability to adapt to profound structural changes. The findings open new avenues for rehabilitation research, suggesting that therapies could aim to leverage even minimal remaining pathways to help restore function after brain injury. The results indicate that the relationship between the brain’s physical structure and its functional capacity is far more flexible and complex than previously understood.

The study, “Full interhemispheric integration sustained by a fraction of posterior callosal fibers,” was authored by Tyler Santander, Selin Bekir, Theresa Paul, Jessica M. Simonson, Valerie M. Wiemer, Henri Etel Skinner, Johanna L. Hopf, Anna Rada, Friedrich G. Woermann, Thilo Kalbhenn, Barry Giesbrecht, Christian G. Bien, Olaf Sporns, Michael S. Gazzaniga, Lukas J. Volz, and Michael B. Miller.

There's a critical feature making it impossible.

There's a critical feature making it impossible.

Stripped down, lowered, widened, and given more power, the EV concept looks enticing.

© Toyota

It’s an electric race car with wings! But only for SEMA...

© Toyota

Trump has justified the attacks as a necessary escalation to stem the flow of drugs into the United States

© Department of Defense

Over 4,700 transactions, including wire transfers to Russian banks raised red flags in 2019, new documents reveal

© Getty Images

Pharmaceutical company says it has not yet received any ‘relevant complaints’ related to the recalled medication

.jpg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

While Hurricane Melissa has caused destruction in the Atlantic, forecasters have been keeping an eye on developments in the UK

© PA

Here's a look at the faith's beliefs and history — and some common misconceptions about it

© AP1969

Flexible solar panels are thinner, lighter and more versatile than standard ones, making them ideal for curved roofs, campervans and boats

© Getty/iStock

Human-caused climate change is making major hurricanes like Melissa much stronger, faster and ultimately more life-threatening

© AFP via Getty Images

Multiple people were arrested in connection to the plot

© AP

Exclusive: Swedish pop singer says the support slot was ‘such a good opportunity’ to introduce herself to ‘the perfect crowd’ of McRae’s fans

© Getty Images for MTV

Marjorie Taylor Greene stirred controversy Thursday when it was revealed she would appear on the liberal daytime talk show ‘The View’

© Getty Images

The oldest cup competition in football returns for the first round proper with 32 non-league teams dreaming of a magical run

.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© Getty Images

Jaysley Beck’s family say Michael Webber’s attack and the way higher-ups handled her complaint ‘broke something inside her that she couldn’t repair’

© Ranger Steve/Wikimedia

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

The Netherlands election results were announced by Dutch media agency ANP after a nail-biting vote count

© Getty Images

© AP1961

Meningitis can cause life-threatening sepsis and result in permanent damage to the brain or nerves if not treated quickly

© Alamy/PA

The royal will move to a property on the Sandringham estate in Norfolk following his eviction from the Royal Lodge

© PA

Rohit Arya, who was allegedly owed money by government, claimed he had taken 17 children and two adults hostage to ask ‘moral and ethical questions’

.png?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

© X/ANI

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein

They cited human rights law in their defence

© PA Media

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

US President Donald Trump and first lady Melania met their dopplegangers as they greeted trick-or-treaters at the White House Halloween event.

© Reuters

Lower your energy bills and cook healthier meals with these efficient appliances

© The Independent

© PA Archive

© The Associated Press

Andrew’s ties to paedophile Jeffrey Epstein have been a source of humiliation for the royal family for years

© AFP via Getty

© Alan Hunt/Geograph/Getty

Get 10 per cent off holiday parks across the UK with these Away Resorts promo codes

© Pexels

© PA Wire

As versatility and power-packed benches continue to define international rugby, could the sport become even more position-less in the future?

© Getty Images

Zarah Sultana said ‘we’re building a party of the left that can win power and deliver justice’

© PA

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

The primates can critically assess the quality of evidence when faced with choices

© Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

Perez spent four seasons alongside Verstappen at Red Bull

© PA Archive

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Final season of iconic superhero TV series will air next year

© Lionsgate Films

Ofcom has said it is ‘disappointed’ by the mobile provider’s decision

© This Morning/ITV

Get the perfect sofa for your home for less this Black Friday – here’s how

© The Independent

The financial fallout of women going through the menopause is still flying under the radar

© Getty Images/iStockphoto

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© PA Wire

The Empire Family is moving to London to save 14-year-old’s career as content creator

© YouTube/EMPIRE Family

The latest Miguel Delaney: Inside Football newsletter explores Brighton’s data-driven approach, how Jamestown Analytics shapes recruitment, and the secrets behind their scouting edge

© PA Archive

A shrine to the pet has sprung up near where KitKat was killed, with one resident predicting it will “grow and grow” as Day of the Dead approaches

© PA Archive

Exclusive: Aim is to cut road congestion and boost number of passengers using public transport to access terminal

© London City Airport

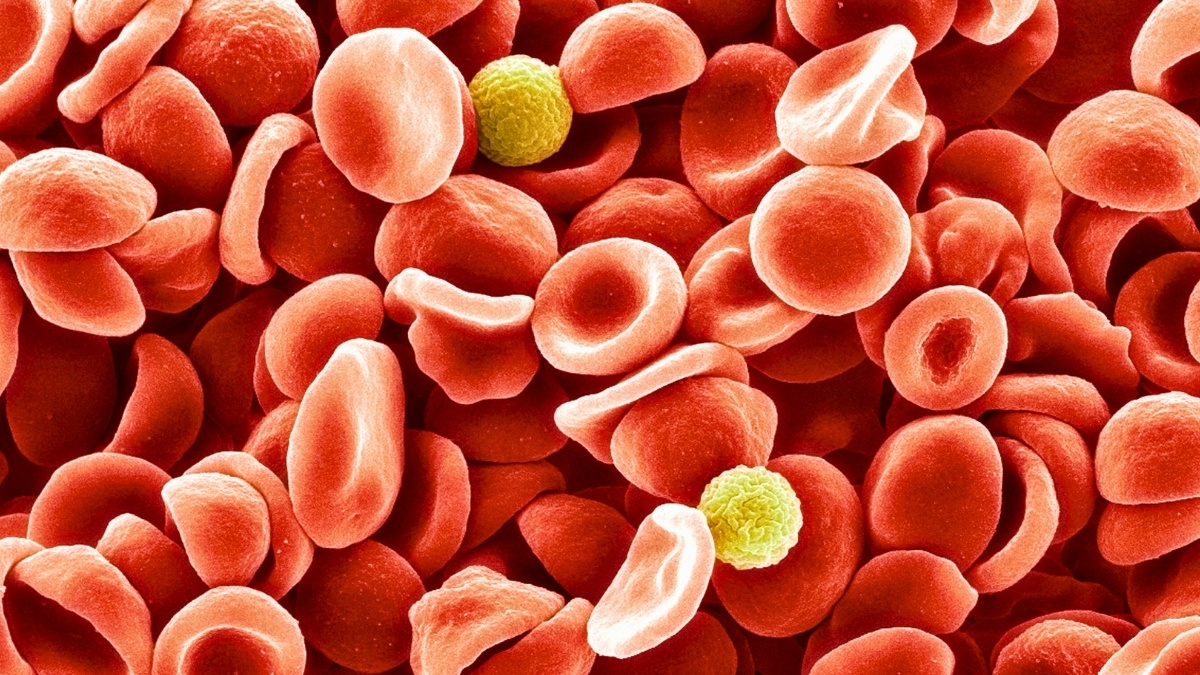

Authorities order sweeping audit of blood banks after public outrage

© Getty

The England international has been sidelined since September with a groin injury, but Maresca is positive about his progress

© PA Wire

Whether you’re cooking crunchy chips, crispy bacon, or a baked potato, these are the air fryers I’d recommend

© Rachael Penn/The Independent

© Paultons Park

© John Walton/PA Wire

Waitrose urgently recalled the Oxo good grips pasta scoop strainer after tests revealed a risk of exposure to carcinogens

© Getty/iStock

Figures show 21 per cent of children living in hygiene poverty avoid playing with others for fear of being judged

© Getty Images

England have reportedly raised concerns over the Wallabies’ ruck actions ahead of the Twickenham clash

© Getty Images

The changes seek to make the competition similar to the successful Indian Premier League

© PA Wire

Gane had bloodied Aspinall’s nose in a competitive first round, which did not reach its conclusion after the Frenchman poked the Briton in both eyes

© Reuters

King Charles’s friend says stripping Andrew of his “prince” title will have been a “stressful” decision for the monarch to make.

© PA Archive

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

From big-name brands to budget-friendly buys, here’s how to save on your next great night’s sleep

© The Independent

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

© Aaron Chown/PA

‘I think what they should have considered is a resurrection,’ Olympic diver lamented

© BBC

© Peter Byrne/PA Wire

Hundreds of demonstrators faced off with police on Friday leading to the deployment of the military and an internet shutdown

© REUTERS

© Getty/iStock

The trio are closing in on a return as Arsenal look to keep their Premier League title push on course

© PA Wire

The stolen sapphire set remained in the Orleans family for more than a century before going on public display

© REUTERS

Sahibas was arrested in Great Abaco after the alleged victim reported the incident to police in Florida

© Marc Shoffman

© Copyright 2018 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Prince Andrew will be stripped of his royal titles, meaning he will no longer be called ‘prince’ or ‘His Royal Highness’

© AP

Hegseth hails new defence deal with India as ‘cornerstone for regional stability’ which includes military and technological cooperation

© X/SecWar

The terrorist had run towards officers ‘aggressively’, holding a knife

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Our community says Andrew’s disgrace highlights the need for a serious examination of the monarchy, with calls for greater transparency, accountability, and a slimmed-down or reformed royal family

© AP

© StackCommerce

© Westend61 | Getty Images

© master1305 | Getty Images

The debate over the most effective models for early childhood education is a longstanding one. While the benefits of preschool are widely accepted, researchers have observed that the academic advantages gained in many programs tend to diminish by the time children finish kindergarten, a phenomenon often called “fade-out.” Some studies have even pointed to potential negative long-term outcomes from certain public preschool programs, intensifying the search for approaches that provide lasting benefits.

This situation prompted researchers to rigorously examine the Montessori method, a well-established educational model that has been in practice for over a century. Their new large-scale study found that children offered a spot in a public Montessori preschool showed better outcomes in reading, memory, executive function, and social understanding by the end of kindergarten.

The research also revealed that this educational model costs public school districts substantially less over three years compared to traditional programs. The findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Montessori method is an educational approach developed over a century ago by Maria Montessori. Its classrooms typically feature a mix of ages, such as three- to six-year-olds, learning together. The environment is structured around child-led discovery, where students choose their own activities from a curated set of specialized, hands-on materials. The teacher acts more as a guide for individual and small-group lessons rather than a lecturer to the entire class.

The Montessori model, which has been implemented in thousands of schools globally, had not previously been evaluated in a rigorous, national randomized controlled trial. This study was designed to provide high-quality evidence on its impact in a public school setting.

“There have been a few small randomized controlled trials of public Montessori outcomes, but they were limited to 1-2 schools, leaving open the question of whether the more positive results were due to something about those schools aside from the Montessori programming,” said study author Angeline Lillard, the Commonwealth Professor of Psychology at the University of Virginia.

“This national study gets around that by using 24 different schools, which each had 3-16 Montessori Primary (3-6) classrooms. In addition, the two prior randomized controlled trials that had trained Montessori teachers (making them more valid) compromised the randomized controlled trial in certain ways, including not using intention-to-treat designs that are preferred by some.”

To conduct the research, the research team took advantage of the admissions lotteries at 24 oversubscribed public Montessori schools across the United States. When a school has more applicants than available seats, a random lottery gives each applicant an equal chance of admission. This process creates a natural experiment, allowing for a direct comparison between the children who were offered a spot (the treatment group) and those who were not (the control group). Nearly 600 children and their families consented to participate.

The children were tracked from the start of preschool at age three through the end of their kindergarten year. Researchers administered a range of assessments at the beginning of the study and again each spring to measure academic skills, memory, and social-emotional development. The primary analysis was a conservative type called an “intention-to-treat” analysis, which measures the effect of simply being offered a spot in a Montessori program, regardless of whether the child actually attended or for how long.

The results showed no significant differences between the two groups after the first or second year of preschool. But by the end of kindergarten, a distinct pattern of advantages had emerged for the children who had been offered a Montessori spot. This group demonstrated significantly higher scores on a standardized test of early reading skills. They also performed better on a test of executive function, which involves skills like planning, self-control, and following rules.

The Montessori group also showed stronger short-term memory, as measured by their ability to recall a sequence of numbers. Their social understanding, or “theory of mind,” was also more advanced, suggesting a greater capacity to comprehend others’ thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. The estimated effects for these outcomes were considered medium to large for this type of educational research.

The study found no significant group differences in vocabulary or a math assessment, although the results for math trended in a positive direction for the Montessori group.

In a secondary analysis, the researchers estimated the effects only for the children who complied with their lottery assignment, meaning those who won and attended Montessori compared to those who lost and did not. As expected, the positive effects on reading, executive function, memory, and social understanding were even larger in this analysis.

“For example, a child who scored at the 50th percentile in reading in a traditional school would have been at the 62nd percentile had they won the lottery to attend Montessori; had they won and attended Montessori, they would have scored at the 71st percentile,” Lillard told PsyPost.

Alongside the child assessments, the researchers performed a detailed cost analysis. They followed a method known as the “ingredients approach,” which accounts for all the resources required to run a program. This included teacher salaries and training, classroom materials, and facility space for both Montessori and traditional public preschool classrooms. One-time costs, such as the specialized Montessori materials and extensive teacher training, were amortized over their expected 25-year lifespan.

The analysis produced a surprising finding. Over the three-year period from ages three to six, public Montessori programs were estimated to cost districts $13,127 less per child than traditional programs. The main source of this cost savings was the higher child-to-teacher ratio in Montessori classrooms for three- and four-year-olds. This is an intentional feature of the Montessori model, designed to encourage peer learning and independence. These savings more than offset the higher upfront costs for teacher training and materials.

“I thought Montessori would cost the same, once one amortized the cost of teacher training and materials,” Lillard said. “Instead, we calculated that (due to intentionally higher ratios at 3 and 4, which predicted higher classroom quality in Montessori) Montessori cost less.”

“Even when including a large, diverse array of schools, public Montessori had better outcomes. These finding were robust to many different approaches to the data. And, the cost analysis showed these outcomes were obtained at significantly lower cost than was spent on traditional PK3 through kindergarten programs in public schools.”

But as with all research, there are limitations. The research included only families who applied to a Montessori school lottery, so the findings might not be generalizable to the broader population. The consent rate to participate in the study was relatively low, at about 21 percent of families who were contacted. Families who won a lottery spot were also more likely to consent than those who lost, which could potentially introduce bias into the results.

“Montessori is not a trademarked term, so anyone can call anything Montessori,” Lillard noted. “We required that most teachers be trained by the two organizations with the most rigorous training — AMI or the Association Montessori Internationale, which Dr. Maria Montessori founded to carry on her work, and AMS or the American Montessori Society, which has less rigorous teacher-trainer preparation and is shorter, but is still commendable. Our results might not extend to all schools that call themselves Montessori. In addition, we had low buy-in as we recruited for this study in summer 2021 when COVID-19 was still deeply concerning. We do not know if the results apply to families that did not consent to participation.”

The findings are also limited to the end of kindergarten. Whether the observed advantages for the Montessori group persist, grow, or fade in later elementary grades is a question for future research. The study authors expressed a strong interest in following these children to assess the long-term impacts of their early educational experiences.

“My collaborators at the American Institutes for Research and the University of Pennsylvania and University of Virginia are deeply appreciative of the schools, teachers, and families who participated, and to our funders, the Institute for Educational Sciences, Arnold Ventures, and the Brady Education Foundation,” Lillard added.

The study, “A national randomized controlled trial of the impact of public Montessori preschool at the end of kindergarten,” was authored by Angeline S. Lillard, David Loeb, Juliette Berg, Maya Escueta, Karen Manship, Alison Hauser, and Emily D. Daggett.

A new study has found that individuals with ADHD have a higher risk of being convicted of a crime, and reveals this connection also extends to their family members. The research suggests that shared genetics are a meaningful part of the explanation for this link. Published in Biological Psychology, the findings show that the risk of a criminal conviction increases with the degree of genetic relatedness to a relative with ADHD.

The connection between ADHD and an increased likelihood of criminal activity is well-documented. Past research indicates that individuals with ADHD are two to three times more likely to be arrested or convicted of a crime. Scientists have also established that both ADHD and criminality have substantial genetic influences, with heritability estimates around 70-80% for ADHD and approximately 50% for criminal behavior. This overlap led researchers to hypothesize that shared genetic factors might partly explain the association between the two.

While some previous studies hinted at a familial connection, they were often limited to specific types of crime or a small number of relative types. The current research aimed to provide a more complete picture. The investigators sought to understand how the risk for criminal convictions co-aggregates, or clusters, within families across a wide spectrum of relationships, from identical twins to cousins. They also wanted to examine potential differences in these patterns between men and women.

“ADHD is linked to higher rates of crime, but it’s unclear why. We studied families to see whether shared genetic or environmental factors explain this connection, aiming to better understand how early support could reduce risk,” said study author Sofi Oskarsson, a researcher and senior lecturer in criminology at Örebro University.

To conduct the investigation, researchers utilized Sweden’s comprehensive national population registers. They analyzed data from a cohort of over 1.5 million individuals born in Sweden between 1987 and 2002. ADHD cases were identified through clinical diagnoses or prescriptions for ADHD medication recorded in national health registers. Information on criminal convictions for any crime, violent crime, or non-violent crime was obtained from the National Crime Register, with the analysis beginning from an individual’s 15th birthday, the age of criminal responsibility in Sweden.